- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

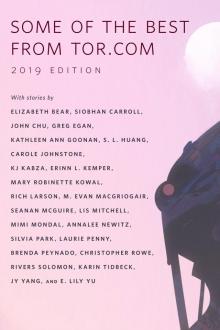

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Page 13

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Read online

Page 13

“I can’t afford to have my underwear dry-cleaned!”

“Just this once. I ordered a Simon, a housekeeping bot, which is essential to your health. It will do your laundry, prepare your meals, and clean your house, but it needs thirty-six training hours.”

“My insurance won’t pay for a bot. Cancel it.”

“I evaluated your budget, and—”

“What budget? My house is paid for. I do my own laundry every Saturday, thank you—”

“Your energy habits are wasteful. I have initiated efficiency measures.”

“Is that why it’s so cold in here?”

“I canceled your newspaper and magazine subscriptions. They waste paper. Hoarding is a serious health risk.”

“I don’t always have time to read them right away.” I feel ridiculous defending myself to this bodiless, bossy thing. “Are you sure you’re not Zoe?”

“You can now access your periodicals digitally, which is still a savings.”

“Reading on screens gives me a headache.”

A swarm of lights like fireflies manifests around me. If I were a kid I’d probably cry out in delight at their flashing ballet as MEDA says, “Keep still. Functional MRI in progress.”

Instead of childish joy, MEDA is documenting a strong urge to curse.

* * *

Surprised that I’m allowed to dress myself, I breakfast on a stash of stale doughnuts the health spies missed. After fending off a neural tweak that would fix my inability to stare at a screen all my waking hours, I’m relieved to find I can restore my newspaper to its rightful place on my morning lawn with a phone call and decide to forgo outrage for the rest of the day. I’m already exhausted.

Despite trying to pretend it’s all a happy lucid dream, I’m annoyed but resolutely not outraged to see the Simon waiting on the front porch, advertising to the entire neighborhood that I’m in need of help.

The humanoid Simon, with its smiling face and big eyes, takes my arm and tries to help me down the front walk and into the sleek, waiting pod, but I beat it off with my cane. Then, chiefly because I’m afraid I won’t be able to work the clutch in my car, off I go on my first self-driving vehicle adventure, filled not with wonder but raw terror as it zips along the Capital Beltway, a fragile shell among heavy metal behemoths ruining our planet by the second. And that, I actually do believe.

The doctor’s waiting room is empty for the first time ever. An electronic voice directs me to cubicle three. Nan looks up from her computer when I enter, and I’m surprised at her careworn expression.

“What’s wrong?”

“That’s my line,” she says, and we both laugh. She’s a good egg. “This is my last day.”

“But you’ve been here—what, fifteen years?”

“Let’s do this first.” She shows me my records on the computer screen, though, as she says, it’s probably illegal without several levels of releases. She’s clearly become a wild woman. I see my blood pressure, pulse, temperature, blood glucose, and oxygen saturation vary slightly in real time as I watch.

I point to the screen. “What’s this?”

Nan says, “Your limbic system stats. Your amygdalae—there are two—which are important players in brain activity involved in empathic reactions. And actually”— she delves down a few levels, which yields ever-more-more-complex information—“your empathy is quite low today.”

“No kidding.”

“But the good news is”—she grins—“you’re not a sociopath. Not even close, despite your strong tilt toward gloom.”

“Not for want of trying. If I cross the line, does my embedded magus have a cure?”

Nan says, “Indeed! You’d have the option of undergoing a brief spell of neuroplasticity—really expensive on the street, and I wouldn’t mind trying it myself today—with concurrent empathy therapy.”

“Which is?”

“You’d experience being in someone else’s virtual body while they react to faces, events, images, or stories most of us would react to in the same way—sad, happy, and so on—while flooded with the neurochemicals that normal people feel at those times. After a few sessions, your amygdalae are closer to the norm.”

“Sounds exhausting.”

Nan says, “I suppose it could be. Normal feelings generate a certain level of insight as to how our actions might emotionally affect others. We feel empathy, which sociopaths and psychopaths lack. They’re usually naturally charming and amazed at how easily they can con others—maybe they assume everyone else is lying, too.”

“Are there over-empathic people?”

“Sure. Too much empathy can be immobilizing, and very, very painful.” Nan leans back in her office chair. “You know, it’s nice that we can just sit and talk—by now I’d have had to move on to the next patient. They’re now monitored, diagnosed, and treated by our new AI. This is the last time you’ll have to come in.”

“Despite what my daughter’s been telling me, these changes seem to be happening very rapidly.”

Nan says, “Oh, I wondered why it wasn’t happening years ago. Nanotech medicine, wireless transmission of information from swallowed or implanted devices, big data, and AI have been around for a while. Television and self-driving cars were both prototyped in the nineteen twenties, but it took the right cultural and economic environment to push widespread development. Same with this.”

“But, Nan, what will you do now?”

“I’ve hardly had time to think of it. Well, my husband and I could go on a world tour—oh, darn, I almost forgot … the kids are still in college.”

“But you have a doctorate, right?”

“Yes, and after extensive consideration of that and my job experience, the AI has offered me an opportunity to oversee coding for automated forklifts at a mega-warehouse, which has been my dream for years. It seems to believe this offer will relieve them of all contractual obligations to me.”

Her laughter is infectious; when we’re done I’m gasping for breath.

“What kind of AI is this?”

A small vee between her eyes. “The kind that successfully proposed a dazzling income-generating option to MedManage, which Doctor Styne signed up with a few years ago.”

“So when I didn’t read the fine print I assented to the invasive data-gathering operation that’s taken up residence inside me.”

She nods. “MedManage sells metadata to pharmaceutical, imaging, nanodevice, and other R&D entities. Also to the CDC, WHO, governments, and NGOs. Of course, their mission is to provide all of us with excellent health and extend our lives through statistical analysis by AIs.”

“And fix psychopaths,” I add.

“Right. So that humans can continue to experience joy, fear, relief, love, hate—all the wondrous emotions AIs value—and the freedom to pursue our interests, once we’re all job-free. Like they care.” Nan stands and says briskly, “Well, the Simon will do your physical therapy.”

Mindful of my back, I give her a very careful hug. “I’ll miss you, Nan. Let’s have coffee soon, okay?”

* * *

As my pod zips and veers toward home, MEDA calls me. I’m exasperated, but then suppose I should be grateful it’s being polite instead of announcing decrees.

A boy appears on the screen. He has dark, curly hair, and when he sees my face he smiles. I cannot help but smile back. “Hi! I’m Mai. What’s your name?”

He burbles in a language I don’t know, but the screen translates: “Azul! Is my birthday party today? Ezo says she will help!”

“How old are you?”

“Three!”

“Three!” I exclaim. “Who is Ezo?”

He laughs. I catch glimpses of other children behind him, and something familiar—a white refugee tent.

“Where are you?”

“Balloons!”

The connection is severed.

“MEDA, please return my last call.”

“I can’t.”

“Where did it come from? Why

did he call me?”

“I don’t know.”

By the time I’m home, I’ve spoken with three supervisors, all of whom assert that they have no record of such an event. No, they cannot trace the communication, and besides, MEDA communications are protected by law, and I am not privy to them.

I’m quite worried about the boy.

Vida

It’s terribly hot here. I long for our summer house in the mountains. But it’s probably gone now, too.

Azul is restored to health, but we argue constantly. Children complain that Azul hit or bit them. I caught him defecating under the trees and yelled, “That’s the kind of thing that made you sick!” He keeps talking about his party. It’s been two months, but he hasn’t forgotten. I should have one for him, but every day is full of turmoil. Hundreds of kids pour in daily, most even more disturbed than us. I’m doing my best, but I can’t be mother, father, and grandmother. I’ve started a message thread with other older kids; some of them know how to deal with the little ones.

Online, I find recommendations for Narrative Exposure Therapy. Basically it’s a process of refugee children with PTSD telling their stories. I organize a network of camp groups to encourage this.

* * *

“How do you feel?” I ask the circle of restless children I’ve gathered, a few afternoons later.

“Mad!”

“Lonely!”

“Angry!”

“Sad!”

Languages mingle with tears in a shouted torrent describing how evil adults killed their families. Most other grown-ups are complicit enablers who ruined the world’s water and air, sucked riches from land they stole, and discarded people like flotsam. With difficulty, I restore one-at-a-time order.

“Another district diverted our water,” Ilya says, her long dreads coiled in an impressive beehive. “We disputed it, but no one cared about us. Our crops failed. Our goats and chickens died. We walked for hundreds of miles and everyone died except my sister and me.”

“We had a school in our village,” says wiry Batul. “Some NGO built it, and sent books, tablets, software, solar panels—even a teacher! Everyone came there to charge their phones and do their banking. My mother got a microloan and opened a café next to it. Then soldiers came and killed all the men. They took my mother and sisters and the older boys. They smashed the solar panels and laughed. ‘Run fast, little boy,’ one of them told me.” He lowers his head and whispers, “I should have tried to kill them. But I ran.”

“I went to visit my aunt,” says Yenena, speaking calmly as tears run down her face. “When I got off the bus on the high road, she didn’t meet me. I walked toward her village and saw dead people. One woman sat on a chair on her porch. I looked inside a church, and people were bent over in the pews, dead. I ran back to the road.

“A van came. A woman in a space suit got out and told me she had to test for a virus. She poked me with a needle, took blood, said I was okay, gave me a shot, and said I could get in. There were other kids in the van. I was afraid because there was no driver. The doctor said everyone was dying of a virus and that I couldn’t go home because everyone there was dead. But how could they all die so fast? I called her a liar and tried to hit her. She grabbed my wrists, said she was sorry, and showed me on her phone that it was true.

“Since then, I just cry. The car brought us here and left to get more kids. She said there’s a new implant that tells a computer when someone gets sick, but it was too expensive for our country. Instead, they bought tanks.”

“My father beat all us kids and our mother, too,” says Serge. “She told us he was a good person inside. That was a lie. He was pure evil. I’m glad he’s dead.”

Azul is walking around holding Ezo, laughing. It’s the only thing that makes him happy. Ezo will talk to anyone, but I’m the only one who can issue executive commands. I can’t imagine why I have custody of superintelligence, but I don’t have time to worry about it, either.

Some children refuse to speak. Others run away, or plug their ears and shout nonsense words. They have seen throats cut, heads blown away, rape, mass executions—unspeakable brutality. It is difficult for me to listen, but those who can speak must have a witness.

So I remain, and try to get them to talk about how to change things.

Stephan asks Ezo to tell us the history of war and aggression, but when I ask it how long it would take, it says, “Longer than any of you will live.”

“Look,” says one of the oldest girls, “maybe that’s the problem. There’s too much history. Maybe we’d be better at fixing things, all of us kids. Adults made these problems. Maybe we can see things more clearly. ”We don’t have as many grudges yet.”

“I have plenty of grudges,” says Batul.

Ezo links us with other groups of refugee children talking about the same things. We are not alone.

“We all want to change this. But how?” I ask.

“Kill everyone who does something bad,” says Ela, who is five.

“Killing is bad,” Joram, who is ten, points out.

“Use CRISPR to change the genes of people who commit acts of violence.”

Karin says, “But if we take away parts of us, will be still be ourselves? When I’m mad, and want to hurt someone, I might not want to kill them. If I think about it, I might just want to yell—I mean, talk to them.”

“That’s called ‘negotiation,’” I say. “Maybe ‘law.’”

“Whose law?” asks Karin. “The law that says any man could beat up my sister if she didn’t do what he told her to do?”

“Is that what it was like where you are from?” asks Ann.

Sami says, “Put a nanotech virus in all weapons that make everyone who picks one up to kill a human being as sad as I was when my—when my sister—”

An older girl holds her as she screams, shakes, and cries.

We should all be crying. The whole world.

Because of who and what we are.

Civilization is a fragile veneer.

Beneath is chaos.

“Fix it, Ezo!” yells Batul. “Fix it, if you’re so smart!” He jumps up and runs away, kicking up dust.

“I’m still learning,” says Ezo. “I don’t know enough.”

Karin stands, and holds up her phone.

“Here’s the UN Declaration of the Rights of the Child. It says that we are all free and equal. We have a right to education, health care, dignity, freedom from fear and want, freedom of speech. I didn’t know I had those rights!”

I touch my aunt’s UN ring, which hangs from a cord around my neck, hidden inside my clothes, and remember her power, her commitment. This vision of a world in which all people, even children, have rights that are respected is what she lived and died for. Can I be as strong as she was?

Sami says, “We need everyone in the camp to read this! Talk about it!”

“I can’t read,” says Ela, “But I can almost.”

“Audio, in seventy-four languages,” says Ezo. There are a lot of pidgins here.

I don’t want to think Ezo sounds like my aunt, but increasingly, she has Ezo’s distinctive accent, low timbre, exact accent. It could easily mimic it by finding my aunt’s phone conversations.

Sami says, “There are sixty-five million refugee children in the world. It says that’s how many people live in France.”

It’s difficult to understand that number.

“When people hurt us, why can’t we just hurt them back?” demands Nabil. “Only worse?”

Lesedi stands and crosses her arms. The festive scarves that she pulled from our pallet of donated clothing, purple and green and red, swirl around this small, fierce goddess. “Because other people have feelings, too!” She glares at us all around the circle, gives a sharp nod, and sits.

“Not the ones who killed our families.” says Nabil. “There are so many of us here because there are so many more of them. I wish I could put them inside my game and kill them all.” He takes aim. “Pow!”

>

“I play other games online,” says Ann. “We build communities. We fix problems. If we could put everything inside that game, we could all fix it together.”

Many of us have grown up playing similar online cooperative world-building games with children and adults near and far. In these games, we create societies, work as teams to improve every aspect of life as the need arises, negotiate road-building, budgets, school curriculums. We discuss right and wrong. We learn our own weaknesses and strengths, hone our skills.

“We can build our own game,” I say. “I’ll teach you how. Ezo, are you open-source?”

“I can provide you with an open-source space.”

“Then we can do it! I’m going to teach all of you to code.”

“We’ll be Team Ezo!” says Nabil.

“And we’ll stop war,” says Ann. “Ezo, play us some dancing music!”

In the sunlight of the waning afternoon, all the children in the circle are seized with genuine enthusiasm. Ezo takes over the loudspeakers, and plays Bob Marley singing, “Get up, stand up! Stand up for your rights,” and then finds antiwar songs from culture after culture, in language after language, many fresh-minted in answer to today’s specific horrors, but all hopeful. I know this because when a new one begins, everyone stands listening for a second, and then, across the camp, voices unite in recognition—sometimes few, but often, many.

The din of them dancing and cheering is overwhelming. I dance too, losing myself in the simple fact of our present safety, not daring to hope.

Later, Azul wakes screaming from nightmares, as he does every night. I hold him tight, and vow that we will end war, human predation, and the terrors these children deal with daily.

We can’t do it alone. I have no idea what form such radical change might take. It would be a world that has never existed before.

Kind of like Ezo.

Mai

A week after my unfortunate yoga adventure, I am improved enough to return to work. When I emerge from the Metro, rejoicing that the escalator works, it seems that there are more self-driving pods than just a week ago. Maybe an SI has been unleashed, a good one, and Zoe’s dream is coming true.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3