- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

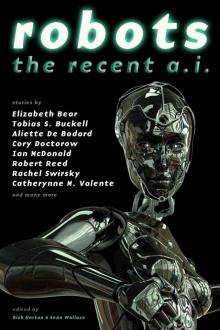

Robots: The Recent A.I. Page 17

Robots: The Recent A.I. Read online

Page 17

“The Shalimar Gardens,” says A.J. Rao in the base of her skull. “Paradise as a walled garden.”

And as he speaks, a wave of transformation breaks across the garden, sweeping away the decay of the twenty-first century. Trees break into full leaf, flower beds blossom, rows of terracotta geranium pots march down the banks of the charbagh channels which shiver with water. The tiered roofs of the pavilion gleam with gold leaf, peacocks fluster and fuss their vanities, and everything glitters and splashes with fountain play. The laughing families are swept back into Mughal grandees, the old men in the park transformed into malis sweeping the gravel paths with their besoms.

Esha claps her hands in joy, hearing a distant, silver spray of sitar notes. “Oh,” she says, numb with wonder. “Oh!”

“A thank you, for what you gave me last night. This is one of my favorite places in all India, even though it’s almost forgotten. Perhaps, because it is almost forgotten. Aurangzeb was crowned Mughal Emperor here in 1658, now it’s an evening stroll for the basti people. The past is a passion of mine; it’s easy for me, for all of us. We can live in as many times as we can places. I often come here, in my mind. Or should I say, it comes to me.”

Then the jets from the fountain ripple as if in the wind, but it is not the wind, not on this stifling afternoon, and the falling water flows into the shape of a man, walking out of the spray. A man of water, that shimmers and flows and becomes a man of flesh. A.J. Rao. No, she thinks, never flesh. A djinn. A thing caught between heaven and hell. A caprice, a trickster. Then trick me.

“It is as the old Urdu poets declare,” says A.J. Rao. “Paradise is indeed contained within a wall.”

It is far past four but she can’t sleep. She lies naked—shameless—but for the ’hoek behind her ear on top of her bed with the window slats open and the ancient airco chugging, fitful in the periodic brownouts. It is the worst night yet. The city gasps for air. Even the traffic sounds beaten tonight. Across the room her palmer opens its blue eye and whispers her name. Esha.

She’s up, kneeling on the bed, hand to hoek, sweat beading her bare skin.

“I’m here.” A whisper. Neeta and Priya are a thin wall away on either side.

“It’s late, I know, I’m sorry . . . ”

She looks across the room into the palmer’s camera.

“It’s all right, I wasn’t asleep.” A tone in that voice. “What is it?”

“The mission is a failure.”

She kneels in the center of the big antique bed. Sweat runs down the fold of her spine.

“The conference? What? What happened?” She whispers, he speaks in her head.

“It fell over one point. One tiny, trivial point, but it was like a wedge that split everything apart until it all collapsed. The Awadhis will build their dam at Kunda Khadar and they will keep their holy Ganga water for Awadh. My delegation is already packing. We will return to Varanasi in the morning.”

Her heart kicks. Then she curses herself, stupid, romantic girli. He is already in Varanasi as much as he is here as much is he is at the Red Fort assisting his human superiors.

“I’m sorry.”

“Yes,” he says. “That is the feeling. Was I overconfident in my abilities?”

“People will always disappoint you.”

A wry laugh in the dark of her skull.

“How very . . . disembodied of you, Esha.” Her name seems to hang in the hot air, like a chord. “Will you dance for me?”

“What, here? Now?”

“Yes. I need something . . . embodied. Physical. I need to see a body move, a consciousness dance through space and time as I cannot. I need to see something beautiful.”

Need. A creature with the powers of a god, needs. But Esha’s suddenly shy, covering her small, taut breasts with her hands.

“Music . . . ” she stammers. “I can’t perform without music . . . ” The shadows at the end of the bedroom thicken into an ensemble: three men bent over tabla, sarangi and bansuri. Esha gives a little shriek and ducks back to the modesty of her bedcover. They cannot see you, they don’t even exist, except in your head. And even if they were flesh, they would be so intent on their contraptions of wire and skin they would not notice. Terrible driven things, musicians.

“I’ve incorporated a copy of a sub-aeai into myself for this night,” A.J. Rao says. “A level 1.9 composition system. I supply the visuals.”

“You can swap bits of yourself in and out?” Esha asks. The tabla player has started a slow Natetere tap-beat on the dayan drum. The musicians nod at each other. Counting, they will be counting. It’s hard to convince herself Neeta and Priya can’t hear; no one can hear but her. And A.J. Rao. The sarangi player sets his bow to the strings, the bansuri lets loose a snake of fluting notes. A sangeet, but not one she has ever heard before.

“It’s making it up!”

“It’s a composition aeai. Do you recognize the sources?”

“Krishna and the gopis.” One of the classic Kathak themes: Krishna’s seduction of the milkmaids with his flute, the bansuri, most sensual of instruments. She knows the steps, feels her body anticipating the moves.

“Will you dance, lady?”

And she steps with the potent grace of a tiger from the bed onto the grass matting of her bedroom floor, into the focus of the palmer. Before she had been shy, silly, girli. Not now. She has never had an audience like this before. A lordly djinn. In pure, hot silence she executes the turns and stampings and bows of the One Hundred and Eight Gopis, bare feet kissing the woven grass. Her hands shape mudras, her face the expressions of the ancient story: surprise, coyness, intrigue, arousal. Sweat courses luxuriously down her naked skin: she doesn’t feel it. She is clothed in movement and night. Time slows, the stars halt in their arc over great Delhi. She can feel the planet breathe beneath her feet. This is what it was for, all those dawn risings, all those bleeding feet, those slashes of Pranh’s cane, those lost birthdays, that stolen childhood. She dances until her feet bleed again into the rough weave of the matting, until every last drop of water is sucked from her and turned into salt, but she stays with the tabla, the beat of dayan and bayan. She is the milkmaid by the river, seduced by a god. A.J. Rao did not choose this Kathak wantonly. And then the music comes to its ringing end and the musicians bow to each other and disperse into golden dust and she collapses, exhausted as never before from any other performance, onto the end of her bed.

Light wakes her. She is sticky, naked, embarrassed. The house staff could find her. And she’s got a killing headache. Water. Water. Joints nerves sinews plead for it. She pulls on a Chinese silk robe. On her way to the kitchen, the voyeur eye of her palmer blinks at her. No erotic dream then, no sweat hallucination stirred out of heat and hydrocarbons. She danced Krishna and the one hundred and eight gopis in her bedroom for an aeai. A message. There’s a number. You can call me.

Throughout the history of the eight Delhis there have been men—and almost always men—skilled in the lore of djinns. They are wise to their many forms and can see beneath the disguises they wear on the streets—donkey, monkey, dog, scavenging kite—to their true selves. They know their roosts and places where they congregate—they are particularly drawn to mosques—and know that that unexplained heat as you push down a gali behind the Jama Masjid is djinns, packed so tight you can feel their fire as you move through them. The wisest—the strongest—of fakirs know their names and so can capture and command them. Even in the old India, before the break up into Awadh and Bharat and Rajputana and the United States of Bengal—there were saints who could summon djinns to fly them on their backs from one end of Hindustan to the other in a night. In my own Leh there was an aged aged sufi who cast one hundred and eight djinns out of a troubled house: twenty-seven in the living room, twenty-seven in the bedroom and fifty-four in the kitchen. With so many djinns there was no room for anyone else. He drove them off with burning yoghurt and chilies, but warned: do not toy with djinns, for they do nothing without a price, and though

that may be years in the asking, ask it they surely will.

Now there is a new race jostling for space in their city: the aeais. If the djinni are the creation of fire and men of clay, these are the creation of word. Fifty million of them swarm Delhi’s boulevards and chowks: routing traffic, trading shares, maintaining power and water, answering inquiries, telling fortunes, managing calendars and diaries, handling routine legal and medical matters, performing in soap operas, sifting the septillion pieces of information streaming through Delhi’s nervous system each second. The city is a great mantra. From routers and maintenance robots with little more than animal intelligence (each animal has intelligence enough: ask the eagle or the tiger) to the great Level 2.9s that are indistinguishable from a human being 99.99 percent of the time, they are a young race, an energetic race, fresh to this world and enthusiastic, understanding little of their power.

The djinns watch in dismay from their rooftops and minarets: that such powerful creatures of living word should so blindly serve the clay creation, but mostly because, unlike humans, they can foresee the time when the aeais will drive them from their ancient, beloved city and take their places.

This durbar, Neeta and Priya’s theme is Town and Country: the Bharati mega-soap that has perversely become fashionable as public sentiment in Awadh turns against Bharat. Well, we will just bloody well build our dam, tanks or no tanks; they can beg for it, it’s our water now, and, in the same breath, what do you think about Ved Prakash, isn’t it scandalous what that Ritu Parvaaz is up to? Once they derided it and its viewers but now that it’s improper, now that it’s unpatriotic, they can’t get enough of Anita Mahapatra and the Begum Vora. Some still refuse to watch but pay for daily plot digests so they can appear fashionably informed at social musts like Neeta and Priya’s dating durbars.

And it’s a grand durbar; the last before the monsoon—if it actually happens this year. Neeta and Priya have hired top bhati-boys to provide a wash of mixes beamed straight into the guests’ ’hoeks. There’s even a climate control field, laboring at the limits of its containment to hold back the night heat. Esha can feel its ultrasonics as a dull buzz against her molars.

“Personally, I think sweat becomes you,” says A.J. Rao, reading Esha’s vital signs through her palmer. Invisible to all but Esha, he moves beside her like death through the press of Town and Countrified guests. By tradition the last durbar of the season is a masked ball. In modern, middle-class Delhi that means everyone wears the computer-generated semblance of a soap character. In the flesh they are the socially mobile, dressed in smart-but-cool hot season modes, but, in the mind’s eye, they are Aparna Chawla and Ajay Nadiadwala, dashing Govind and conniving Dr. Chatterji. There are three Ved Prakashes and as many Lal Darfans—the aeai actor that plays Ved Prakash in the machine-made soap. Even the grounds of Neeta’s fiancé’s suburban bungalow have been enchanted into Brahmpur, the fictional Town where Town and Country takes place, where the actors that play the characters believe they live out their lives of celebrity tittle-tattle. When Neeta and Priya judge that everyone has mingled and networked enough, the word will be given and everyone will switch off their glittering disguises and return to being wholesalers and lunch vendors and software rajahs. Then the serious stuff begins, the matter of finding a bride. For now Esha can enjoy wandering anonymous in company of her friendly djinn.

She has been wandering much these weeks, through heat streets to ancient places, seeing her city fresh through the eyes of a creature that lives across many spaces and times. At the Sikh gurdwara she saw Tegh Bahadur, the Ninth Guru, beheaded by fundamentalist Aurangzeb’s guards. The gyring traffic around Vijay Chowk melted into the Bentley cavalcade of Mountbatten, the Last Viceroy, as he forever quit Lutyen’s stupendous palace. The tourist clutter and shoving curio vendors around the Qutb Minar turned to ghosts and it was 1193 and the muezzins of the first Mughal conquerors sang out the adhaan. Illusions. Little lies. But it is all right, when it is done in love. Everything is all right in love. Can you read my mind? she asked as she moved with her invisible guide through the thronging streets, that every day grew less raucous, less substantial. Do you know what I am thinking about you, Aeai Rao? Little by little, she slips away from the human world into the city of the djinns.

Sensation at the gate. The male stars of Town and Country buzz around a woman in an ivory sequined dress. It’s a bit damn clever: she’s come as Yana Mitra, freshest fittest fastest boli sing-star. And boli girlis, like Kathak dancers, are still meat and ego, though Yana, like every Item-singer, has had her computer avatar guest on T’n’C.

A.J. Rao laughs. “If they only knew. Very clever. What better disguise than to go as yourself. It really is Yana Mitra. Esha Rathore, what’s the matter, where are you going?”

Why do you have to ask don’t you know everything then you know it’s hot and noisy and the ultrasonics are doing my head and the yap yap yap is going right through me and they’re all only after one thing, are you married are you engaged are you looking and I wish I hadn’t come I wish I’d just gone out somewhere with you and that dark corner under the gulmohar bushes by the bhati-rig looks the place to get away from all the stupid stupid people.

Neeta and Priya, who know her disguise, shout over, “So Esha, are we finally going to meet that man of yours?”

He’s already waiting for her among the golden blossoms. Djinns travel at the speed of thought.

“What is it, what’s the matter. . . ?”

She whispers, “You know sometimes I wish, I really wish you could get me a drink.”

“Why certainly, I will summon a waiter.”

“No!” Too loud. Can’t be seen talking to the bushes. “No; I mean, hand me one. Just hand me one.” But he cannot, and never will. She says, “I started when I was five, did you know that? Oh, you probably did, you know everything about me. But I bet you didn’t know how it happened: I was playing with the other girls, dancing round the tank, when this old woman from the gharana went up to my mother and said, I will give you a hundred thousand rupees if you give her to me. I will turn her into a dancer; maybe, if she applies herself, a dancer famous through all of India. And my mother said, why her? And do you know what that woman said? Because she shows rudimentary talent for movement, but, mostly, because you are willing to sell her to me for one lakh rupees. She took the money there and then, my mother. The old woman took me to the gharana. She had once been a great dancer but she got rheumatism and couldn’t move and that made her bad. She used to beat me with lathis, I had to be up before dawn to get everyone chai and eggs. She would make me practice until my feet bled. They would hold up my arms in slings to perform the mudras until I couldn’t put them down again without screaming. I never once got home—and do you know something? I never once wanted to. And despite her, I applied myself, and I became a great dancer. And do you know what? No one cares. I spent seventeen years mastering something no one cares about. But bring in some boli girl who’s been around five minutes to flash her teeth and tits. . . . ”

“Jealous?” asks A.J. Rao, mildly scolding.

“Don’t I deserve to be?”

Then bhati-boy One blinks up “You Are My Soniya” on his palmer and that’s the signal to demask. Yane Mitra claps her hands in delight and sings along as all around her glimmering soapi stars dissolve into mundane accountants and engineers and cosmetic nano-surgeons and the pink walls and roof gardens and thousand thousands stars of Old Brahmpur melt and run down the sky.

It’s seeing them, exposed in their naked need, melting like that soap-world before the sun of celebrity, that calls back the madness Esha knows from her childhood in the gharana. The brooch makes a piercing, ringing chime against the cocktail glass she has snatched from a waiter. She climbs up on to a table. At last, that boli bitch shuts up. All eyes are on her.

“Ladies, but mostly gentlemen, I have an announcement to make.” Even the city behind the sound-curtain seems to be holding its breath. “I am engaged to be married!” Gasps

. Oohs. Polite applause who is she, is she on tivi, isn’t she something arty? Neeta and Priya are wide-eyed at the back. “I’m very very lucky because my husband-to-be is here tonight. In fact, he’s been with me all evening. Oh, silly me. Of course, I forgot, not all of you can see him. Darling, would you mind? Gentlemen and ladies, would you mind slipping on your hoeks for just a moment. I’m sure you don’t need any introduction to my wonderful wonderful fiancé, A.J. Rao.”

And she knows from the eyes, the mouths, the low murmur that threatens to break into applause, then fails, then is taken up by Neeta and Priya to turn into a decorous ovation, that they can all see Rao as tall and elegant and handsome as she sees him, at her side, hand draped over hers.

She can’t see that boli girl anywhere.

He’s been quiet all the way back in the phatphat. He’s quiet now, in the house. They’re alone. Neeta and Priya should have been home hours ago, but Esha knows they’re scared of her.

“You’re very quiet.” This, to the coil of cigarette smoke rising up toward the ceiling fan as she lies on her bed. She’d love a bidi; a good, dirty street smoke for once, not some Big Name Western brand.

“We were followed as we drove back after the party. An aeai aircraft surveilled your phatphat. A network analysis aeai system sniffed at my router net to try to track this com channel. I know for certain street cameras were tasked on us. The Krishna Cop who lifted you after the Red Fort durbar was at the end of the street. He is not very good at subterfuge.”

Esha goes to the window to spy out the Krishna Cop, call him out, demand of him what he thinks he’s doing?

“He’s long gone,” says Rao. “They have been keeping you under light surveillance for some time now. I would imagine your announcement has upped your level.”

“They were there?”

“As I said . . . ”

“Light surveillance.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

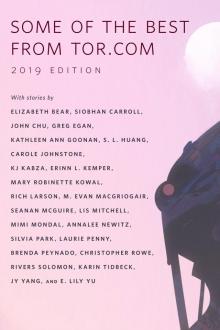

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3