- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

A Companion to Wolves Page 17

A Companion to Wolves Read online

Page 17

“Even when there’s ten of us?”

Sokkolfr glanced over his shoulder; three other wolves, and three men. “Follow, then,” he said, and the five men and their brothers and sister went down into the darkness, in pursuit of whatever fled.

It wasn’t a long chase, though they heard the fighting follow them. They brought the troll to bay against a doorway like the one that had led into the nursery Isolfr remembered all too vividly, and when they had it revealed in the torchlight, Isolfr understood why it had not seemed to move like other trolls. “Priest,” he said, guessing by the drilled stones hanging in the thing’s greasy gray mane and the colored spirals tattooed blue and crimson on its face—and recognizing, horribly, the crude designs on its beaten copper collar as those written in blood at the trellherig near Ravndalr.

“Witch,” another man said, a wolfcarl of Vestfjorthr whose name Isolfr did not know. “It’s a sow.”

“So it is,” Sokkolfr said, and stepped forward, swinging torch and axe.

The old troll did not die easy, and her squeals brought more down on them, two, then a half-dozen. Isolfr stuck to Viradechtis’ side like a burr in her thick barred coat, almost not recognizing his wolf in the frothing, raging creature who reared up and battled trolls fang to tusk, who slashed rubbery, great-thewed legs, who fought through to the nursery beyond the dead trellwitch and did slaughter there like a fox run mad in a chicken coop.

Half the kittens were dead already when they burst into the chamber, spread in a gory fan around one of the holes Isolfr still thought of as the work of stone mice. It was a bigger hole this time, big enough for a trellwolf, and once she had dealt with the rest of the kittens, the trellwolf in the room moved toward it, her brush slung low in determination.

“Sister,” Isolfr said, warning. Viradechtis ignored him, showing no interest in the other door—through which Isolfr could still hear Sokkolfr’s battlecries, among others. She circled piles of rags and nesting filth, stopping to sniff the body of each kitten as she passed—the ones she had murdered and the ones that they had found already dead.

Isolfr almost leaped out of his boots when the third one she nosed startled upward with a shriek. She lunged after it, and—frantic—the thing spidered toward the mouse-hole. “Sister, no!” Isolfr shouted.

He might as well have shouted into the void. She was gone, and there was nothing for it but that he go after her, into the dark of that unknown hole. Because never follow a running troll, Grimolfr had said.

But he had also said never leave your wolf, and Viradechtis was not any wolf. She was the future of the Wolfmaegth, rolled up in a barred red and black hide.

Gingerly balancing his torch, Isolfr followed his sister down into the dark.

Trolls had not dug this tunnel; that, he knew before he had gone three steps. It was too low, for one thing—a bigger man could not have squeezed through—and the grade, while steep, was not wrong in the way that trellwarren tunnels were wrong.

Stone mice, he thought. He could feel Viradechtis ahead of him, feel her fury at the troll kitten that scuttled just ahead of her. But it was not only his sister’s nose telling him this tunnel did not belong to the warren; he could smell it himself, sharper, cleaner than anything dug by trolls. And then a stronger scent, pungent, musky, and Isolfr came to the bottom of the tunnel, falling over Viradechtis before he realized she was there. And found himself face to face with the kitten, freshly dead, black blood still oozing out of its maw—

—pinned to the tunnel floor by a weapon that bore the same resemblance to a troll-spear that Viradechtis did to a mangy village mongrel.

He rolled, instinct moving him while rational thought stared blankly, but before he could get to his feet, the spear came down again, hard, fast, and pinned his shoulder. Most of what it pierced was cloth and leather, but not all. His torch fell and guttered, but did not quite go out.

Blinking against pain and smoke, Isolfr looked up. He found himself regarding, from a not very great distance, a thin, bony face with a jutting nose, curling, tufted eyebrows, heavy sideburns and a mass of elf-locked hair in which metal and jewels gleamed, catching and reflecting the torchlight like stars. It put its head on one side to look at him, eyes small and bright. Quartz, Isolfr thought. I’ve found the stone mice.

Then it said, in a high harsh voice like the wind howling through the narrow defiles of the Iskryne, “Is this your beast?”

He realized, after a moment’s blankness, that it wasn’t talking to him. It was talking to Viradechtis, who was frozen by the wall, crouched and hesitating, Isolfr thought, because the weird gnarled little person with the spear was bent so close to his throat. She growled, low and soft, and coiled herself like a springing snake.

“I’m not a beast,” Isolfr said, getting his left arm up to grab the shaft of the spear. He thought it had cut a furrow across the top of his shoulder rather than pinning through meat or catching bone, and that was good, because it meant he could probably still use his right arm if he got the stone mouse off him.

It cocked its head from him to Viradechtis, the beads in its ratted locks chiming like crystal, and leaned down into his face, its weight on the spear ripping a gasp of pain out of Isolfr’s throat. “Not a beast, you say?” There were harmonics in the voice, under and overtones, like the far-flung challenge of a wolf’s howl. It rang along Isolfr’s nerves like the bright clatter of the beads in its hair. “And yet you come following your mistress the wolf-queen into the dark under Ice-crown like a good beast, and I see her as ready to defend you as if you were her cub. What then, if not a beast, who speaks with only half a tongue?”

Half a tongue. He thought at first it was a threat, and then he realized it meant his own voice, his speech, unaccented by harmonics. “She is my sister,” Isolfr said. “Her name is Viradechtis, and mine is Isolfr.”

“Isolfr?” It blinked, a big froggy blink for such sharp little eyes. “You’re no wolf-get.” It backed away, though, freeing the blade of its spear from his shoulder with a jerk that left his eyesight blurry. Hot blood spilled down his chest under his tunic; Viradechtis was instantly beside him, whining, trying to nose the wound through his jerkin as the bent little man retreated and Isolfr got his first good look at its weapon and the metal and trellbone ornaments on its leather apron. The craftsmanship was foreign, beautiful.

“Svartalf,” Isolfr said, on a shocked breath. “I’ve come to Nidavellir.”

“No,” it said, and crouched back on its ropy haunches, balancing against the planted butt of the spear, its torch held casually in its left hand. “You’ve come to Trellheim. Or under it. Nidavellir is deeper still.”

Using Viradechtis as a prop, Isolfr sat. His axe lay beside him. The svartalf’s troll-spear had three times the reach, and it wasn’t at any kind of a disadvantage. He left the axe where it was and tore his sleeve to staunch his wound. He had no idea what the proper form of address would be, so he guessed. “What’s your name, then, Master Delver?”

The little man smiled, showing jagged teeth that glittered like jewels. That were set with jewels, Isolfr realized, and decorated with fretted latticeworks of silver that gleamed bright without a hint of tarnish. “No Mastersmith yet,” it said. “I am called Tin, of the smith’s guild and the Iron Kinship. My mother’s name is Molybdenum; the eldest-mother of the line is Copper. If you say you’re not a beast, then you must be a man.”

“Not according to some,” Isolfr answered bitterly, and then looked up and tipped his head at his host. “I’m a man. A wolfcarl; my name you have, my styling is Viradechtisbrother.”

It nodded, and stood. “And what brings you to Trellheim, Isolfr Viradechtisbrother?”

“I come to kill trolls.”

“Ah!” That smile again, the glitter of teeth, the chime of beaded elflocks as it—as Tin—half-scuttled, half-hopped forward. “Excellent. And the queen-wolf too?”

“We had no intention to invade the mountains,” Isolfr said carefully. “We came because the trolls h

ave been raiding our homes, killing our men and our cattle, and we wished to burn the infection out at the source.”

“Then how unfortunate for you that most of the trolls are already gone,” Tin said, gesturing with his spear for Isolfr to rise. Isolfr managed it, clinging to Viradechtis’ ruff, and Tin did not comment when Isolfr bent down woozily and retrieved his axe. “Or perhaps it is fortunate, since some of your men and wolves will live to fight again, and I do not think it would be so if the warrens had been full.” He gestured Isolfr along the corridor, and Isolfr, with a longing glance toward the tunnel he and Viradechtis had scrambled down, went. There was no way his wolf could go back up that slope, and—frankly—he doubted his own ability to make it with only one working arm, even if Tin would let him try.

“Where did they go? The trolls.”

Tin shrugged. “Out of their warrens. I care not where.”

“Why out of their warrens? Why at midsummer?” The torch in Tin’s hand sent his shadow leaping before him. He had to duck and crouch, one arm slung over his wolf’s shoulder for support, to enter the tunnel Tin’s spear-jerks directed him toward. He turned back over his wounded shoulder to get a look at the svartalf, and blinded himself.

“Because we drive them out,” Tin said, and rattled the butt of his spear encouragingly against the wall. “And take their warrens for our own.”

“Oh,” said Isolfr. And again, “Why?”

A strange noise. Laughter? “In sooth, you are no beast, for such unflagging curiosity can only belong to creatures who are awake, whether they can sing or no.” And he was uneasily aware that those words, awake and sing, meant something to the svartalf that they did not mean to him. “But those reasons, wolfbrother, are not mine to tell you, even if I wished to.”

“Where are you taking me?” Isolfr asked after a moment. The tunnel was sloping down again, and he could not help remembering what Tin had said about Trellheim and Nidavellir.

“To the—” Tin said a word Isolfr did not know, and the strange harmonics of the svartalf’s voice made it impossible for him even to guess at its meaning. He glanced over his shoulder inquiringly, and Tin hissed through his jeweled teeth and said, “The … Master Harrier, I suppose you might say. The leader of this our expedition.”

“You killed the kittens,” Isolfr said and cursed his own slow wits. And—of course—that skull he’d seen in the first nursery hadn’t been a human skull at all, but a svartalf skull.

“Kittens, thralls, artisans, priests … we open rooms and kill what we find within them. Then we retreat, and the trolls are too wise to seek us in the lower tunnels.”

Never follow a running troll. Isolfr shuddered.

“We are a small people, wolfbrother. We rely on cunning where trolls rely on strength. And men, apparently, rely on wolves.”

“We do not have tunnels to retreat to,” Isolfr said, feeling a vague sense of defensiveness on behalf of his race.

“No, you live on the skin of the earth, yes? Or so I was told as a child.”

“Yes,” Isolfr said, a little uncertainly.

“And the bright goddesses watch you always?” Tin sounded genuinely curious.

“The sun and moon, you mean? Yes, I suppose so.”

“The world is full of marvels,” Tin said. “You will want to watch your head, I believe, for you are much taller, and although it is shameful to delve in haste, sometimes it is also necessary.”

Isolfr, who was already ducked almost double, was about to say that watching his head more closely would require a second pair of eyes, when the hand he had in front of him for precisely that purpose jarred hard against a lump of rock hanging down from the ceiling of the tunnel like a tooth. He couldn’t quite bite back a yelp.

“Chalcopyrite. Er. Copper ore, you see,” Tin said, not quite apologetically, but as one who realized that strange creatures might not understand the natural and obvious. “We haven’t time to mine the vein properly now, and it would be waste more shameful than haste to discard it in the rubble.”

“Of course,” Isolfr said politely and proceeded from there with even greater caution.

The way went downward until Isolfr swore he could feel the weight of the mountains like Mimir’s knee on his back. Better Mimir’s knee than Tin’s troll-spear, though. Viradechtis seemed to agree—or, perhaps, to feel that there was no need for caution. She trotted forward boldly, nails clicking on the hewn stone underfoot, stopping every dozen yards to crane back over her shoulder and see what might be taking Isolfr so long.

Isolfr wished he were better reassured by her lack of caution, but he followed with what trust was in him and eventually they came to a tunnel that was greater than the first, where he could stand upright. His thighs and calves and his lower back protested when he straightened, to the point where he thought he might almost rather have stayed cramped. This tunnel was nothing like the rough-hewn one that led to the trellwarren; it was spacious, wide enough for five svartalfar or three men abreast, and tallow lanterns flickered every few hundred feet, casting warm yellow pools of light through panes that looked like smoke-ambered crystal. By the nearest, Isolfr could make out the fine fluted patterns that curled along the walls of the hall. Hall, because he could not in honesty call it a tunnel. Not after the trellwarren.

“Follow me,” Tin said, striding past as if he no longer needed to keep Isolfr under watch.

That alone would have warned Isolfr that his behavior would be measured. The high queer resonance of svartalfar voices rang around corners and echoed from place to place, and Isolfr could no more say whence they spoke than he could say how many there were. He laid a hand on Viradechtis’ shoulder, and as she seemed inclined to follow Tin, so he followed her.

Finally, he could tell that the voices—or some of them, at least—came from ahead. There was more light there, too, pools of it, and it occurred to him that there must be ventilation shafts somewhere because the air he breathed was cool and fresh, and the fires burned clear. “Hold your spears,” Tin said and stepped forward through a narrow place in the hall. “I am accompanied.”

Viradechtis was untroubled, and so Isolfr went boldly, comforting himself that if he died here, it would be with his wolf at his side.

What he found beyond the stricture in the passage was a cavern perhaps the size of a herdsman’s hut, a dozen or so svartalfar gathered around a fire that flickered hot and ghostly close to the coals. They looked as like Tin as Isolfr looked like his threatbrothers—which was to say, to a type, but not a matched set—and somehow that simple hominess made it possible for him to draw a breath.

“Fellows,” Tin said, standing aside as more than one of his companions laid hands on their weapons, “May I present Isolfr Viradechtisbrother, and his mistress, Viradechtis Konigenwolf.”

The svartalfar tipped their heads to look at him, birdlike, first one eye and then the other. He could see now, in the better light, that they had long arms for their low stature. He could not tell the length of their legs, but he wondered if their lack of height was more a matter of twisted backbones. Certainly their reach—as one stretched a hand out, beckoning imperiously, jewels gleaming on his hand—was frightening. “Come closer to the light, creature.”

Viradechtis regarded them all with lively interest, and Isolfr knew that creature had been directed at him. He swallowed hard against a mixture of indignation and anxiety, and stepped forward.

“So,” said the svartalf who had spoken. “We have heard your racket echoing down through the trellwarren and wondered what manner of beast it was that sang so.” And again, sing did not mean what Isolfr was accustomed to it meaning.

Tin coughed and said, “Not beast. He says he is a man.”

Eyebrows went up around the circle, rendering the svartalfar’s faces even more grotesque in the firelight. “There have not been men seen near Nidavellir since my mother’s mother’s time,” said one of the other svartalfar. “What brings you north then, creature, or do you but follow where your mistre

ss leads?”

“She is not my mistress,” Isolfr said carefully, “any more than I am her master. She is my sister. And she and I and the Wolfmaegth and wolfless men of the North came into these mountains to kill trolls. We did not know that Nidavellir lay beneath them.”

“Then where did you imagine it to lie?” He could not tell if their curiosity was honest, as Tin’s had been, or if they mocked him.

“You say men have not been seen near Nidavellir since your grandmother’s time,” he said, with a bow to the svartalf who had so spoken. “It is more generations of men than that since we last had any knowledge of the svartalfar. I knew of you—before today—only from stories.”

“As it should be,” another svartalf said. This one, he thought, was older than the others; it had something of an old man’s querulousness. “We want nothing to do with men.”

“Yes. Why did you bring it down here, Tin?”

“The queen-wolf would hardly have stirred without him,” Tin said, unperturbed by the note of accusation. “And it is true, as he says, that he and his kind are killing trolls. The warren above us is no more.”

That seemed to please them, if he was hearing the harmonics of their mutterings correctly. But, “We want no men in our delvings,” the old svartalf said stridently over the others. “Just because it kills trolls, Tin, doesn’t mean it’s a friend.”

“I do not wish to be an enemy,” Isolfr said, and that made all of them laugh.

“With a queen-wolf at your side, we will believe you,” said the svartalf whom he had tentatively identified as the jarl. It cocked its head at him. “Though we would believe you more readily if you would put down your axe.”

Isolfr hesitated only a moment before complying. The odds against him were not substantially worse without the axe, and Viradechtis still seemed content to sit and observe. They might care little for him, but he thought they would not kill him in the face of Viradechtis’ obvious favor.

The jarl leaned sideways—that terrifying reach again—and picked up his axe, turning it over in his long, knob-knuckled hands. “Primitive,” he said, “though I imagine your smiths do the best they can, given what they have to work with.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

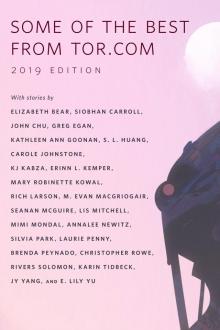

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

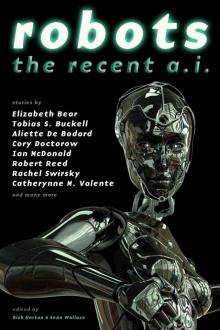

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3