- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

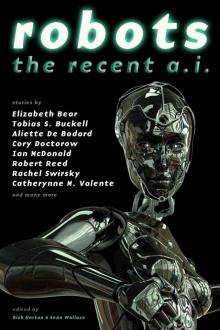

Robots: The Recent A.I. Page 19

Robots: The Recent A.I. Read online

Page 19

“I am aware of them.” He laughs. He has this way now of doing it inside her head. He thinks she likes the intimacy, a truly private joke. She hates it. “All too aware of them.”

“They wanted to warn me. Us.”

“That was kind of them. And me a representative of a foreign government. So that’s why they’d been keeping a watch on you, to make sure you are all right.”

“They thought they might be able to use me to get information from you.”

“Did they indeed?”

The night is so still she can hear the jingle of the elephant harnesses and the cries of the mahouts as they carry the last of the guests down the long processional drive to their waiting limos. In a distant kitchen a radio jabbers.

Now we will see how human you are. Call him out. At last A.J. Rao says, “Of course. I do love you.” Then he looks into her face. “I have something for you.”

The staff turn their faces away in embarrassment as they set the device on the white marble floor, back out of the room, eyes averted. What does she care? She is a star. A.J. Rao raises his hand and the lights slowly die. Pierced-brass lanterns send soft stars across the beautiful old zenana room. The device is the size and shape of a phatphat tire, chromed and plasticed, alien among the Mughal retro. As Esha floats over the marble toward it, the plain white surface bubbles and deliquesces into dust. Esha hesitates.

“Don’t be afraid, look!” says A.J. Rao. The powder spurts up like steam from boiling rice, then pollen-bursts into a tiny dust-dervish, staggering across the surface of the disc. “Take the ’hoek off!” Rao cries delightedly from the bed. “Take it off.” Twice she hesitates, three times he encourages. Esha slides the coil of plastic off the sweet-spot behind her ear and voice and man vanish like death. Then the pillar of glittering dust leaps head high, lashes like a tree in a monsoon and twists itself into the ghostly outline of a man. It flickers once, twice, and then A.J. Rao stands before her. A rattle like leaves a snake-rasp a rush of winds, and then the image says, “Esha.” A whisper of dust. A thrill of ancient fear runs through her skin into her bones.

“What is this . . . what are you?”

The storm of dust parts into a smile.

“I-Dust. Micro-robots. Each is smaller than a grain of sand, but they manipulate static fields and light. They are my body. Touch me. This is real. This is me.”

But she flinches away in the lantern-lit room. Rao frowns.

“Touch me. . . . ”

She reaches out her hand toward his chest. Close, he is a creature of sand, a whirlwind permanently whipping around the shape of a man. Esha touches flesh to i-Dust. Her hand sinks into his body. Her cry turns to a startled giggle.

“It tickles. . . . ”

“The static fields.”

“What’s inside?”

“Why don’t you find out?”

“What, you mean?”

“It’s the only intimacy I can offer. . . . ” He sees her eyes widen under their kohled make-up. “I think you should hold your breath.”

She does, but keeps her eyes open until the last moment, until the dust flecks like a dead tivi channel in her close focus. A.J. Rao’s body feels like the most delicate Vaanasi silk scarf draped across her bare skin. She is inside him. She is inside the body of her husband, her lover. She dares to open her eyes. Rao’s face is a hollow shell looking back at her from a perspective of millimeters. When she moves her lips, she can feel the dust-bots of his lips brushing against hers: an inverse kiss.

“My heart, my Radha,” whispers the hollow mask of A.J. Rao. Somewhere Esha knows she should be screaming. But she cannot: she is somewhere no human has ever been before. And now the whirling streamers of i-Dust are stroking her hips, her belly, her thighs. Her breasts. Her nipples, her cheeks and neck, all the places she loves to feel a human touch, caressing her, driving her to her knees, following her as the mote-sized robots follow A.J. Rao’s command, swallowing her with his body.

It’s Gupshup followed by Chandni Chati and at twelve thirty a photo shoot—at the hotel, if you don’t mind—for FilmFare’s Saturday Special Center Spread—you don’t mind if we send a robot, they can get places get angles we just can’t get the meat-ware and could you dress up, like you did for the opening, maybe a move or two, in between the pillars in the Diwan, just like the gala opening, okay lovely lovely lovely well your husband can copy us a couple of avatars and our own aeais can paste him in people want to see you together, happy couple lovely couple, dancer risen from basti, international diplomat, marriage across worlds in every sense the romance of it all, so how did you meet what first attracted you what’s it like be married to an aeai how do the other girls treat you do you, you know and what about children, I mean, of course a woman and an aeai but there are technologies these days geneline engineering like all the super-duper rich and their engineered children and you are a celebrity now how are you finding it, sudden rise to fame, in every gupshup column, worldwide celebi star everyone’s talking all the rage and all the chat and all the parties and as Esha answers for the sixth time the same questions asked by the same gazelle-eyed girli celebi reporters oh we are very happy wonderfully happy deliriously happy love is a wonderful wonderful thing and that’s the thing about love, it can be for anything, anyone, even a human and an aeai, that’s the purest form of love, spiritual love her mouth opening and closing yabba yabba yabba but her inner eye, her eye of Siva, looks inward, backward.

Her mouth, opening and closing.

Lying on the big Mughal sweet-wood bed, yellow morning light shattered through the jharoka screen, her bare skin good-pimpled in the cool of the airco. Dancing between worlds: sleep, wakefulness in the hotel bedroom, memory of the things he did to her limbic centers through the hours of the night that had her singing like a bulbul, the world of the djinns. Naked but for the ’hoek behind her ear. She had become like those people who couldn’t afford the treatments and had to wear eyeglasses and learned to at once ignore and be conscious of the technology on their faces. Even when she did remove it—for performing; for, as now, the shower—she could still place A.J. Rao in the room, feel his physicality. In the big marble stroll-in shower in this VIP suite relishing the gush and rush of precious water (always the mark of a true rani) she knew AyJay was sitting on the carved chair by the balcony. So when she thumbed on the tivi panel (bathroom with tivi, oooh!) to distract her while she toweled dry her hair, her first reaction was a double-take-look at the ’hoek on the sink-stand when she saw the press conference from Varanasi and Water Spokesman A.J. Rao explaining Bharat’s necessary military exercises in the vicinity of the Kunda Khadar dam. She slipped on the ’hoek, glanced into the room. There, on the chair, as she felt. There, in the Bharat Sabha studio in Varanasi, talking to Bharti from the Good Morning Awadh! News.

Esha watched them both as she slowly, distractedly dried herself. She had felt glowing, sensual, divine. Now she was fleshy, self-conscious, stupid. The water on her skin, the air in the big room was cold cold cold.

“AyJay, is that really you?”

He frowned.

“That’s a very strange question first thing in the morning. Especially after. . . . ”

She cut cold his smile.

“There’s a tivi in the bathroom. You’re on, doing an interview for the news. A live interview. So, are you really here?”

“Cho chweet, you know what I am, a distributed entity. I’m copying and deleting myself all over the place. I am wholly there, and I am wholly here.”

Esha held the vast, powder-soft towel around her.

“Last night, when you were here, in the body, and afterward, when we were in the bed; were you here with me? Wholly here? Or was there a copy of you working on your press statement and another having a high level meeting and another drawing an emergency water supply plan and another talking to the Banglas in Dhaka?”

“My love, does it matter?”

“Yes, it matters!” She found tears, and something beyond; anger choking

in her throat. “It matters to me. It matters to any woman. To any . . . human.”

“Mrs. Rao, are you all right?”

“Rathore, my name is Rathore!” She hears herself snap at the silly little chati-mag junior. Esha gets up, draws up her full dancer’s poise. “This interview is over.”

“Mrs. Rathore Mrs. Rathore,” the journo girli calls after her.

Glancing at her fractured image in the thousand mirrors of the Sheesh Mahal, Esha notices glittering dust in the shallow lines of her face.

A thousand stories tell of the willfulness and whim of djinns. But for every story of the djinni, there are a thousand tales of human passion and envy and the aeais, being a creation between, learned from both. Jealousy, and dissembling.

When Esha went to Thacker the Krishna Cop, she told herself it was from fear of what the Hamilton Acts might do to her husband in the name of national hygiene. But she dissembled. She went to that office on Parliament Street looking over the star-geometries of the Jantar Mantar out of jealousy. When a wife wants her husband, she must have all of him. Ten thousand stories tell this. A copy in the bedroom while another copy plays water politics is an unfaithfulness. If a wife does not have everything, she has nothing. So Esha went to Thacker’s office wanting to betray and as she opened her hand on the desk and the techi boys loaded their darkware into her palmer she thought, this is right, this is good, now we are equal. And when Thacker asked her to meet him again in a week to update the ‘ware—unlike the djinns, hostages of eternity, software entities on both sides of the war evolved at an ever-increasing rate—he told himself it was duty to his warrant, loyalty to his country. In this too he dissembled. It was fascination.

Earth-mover robots started clearing the Kunda Khadar dam site the day Inspector Thacker suggested that perhaps next week they might meet at the International Coffee House on Connaught Circus, his favorite. She said, my husband will see. To which Thacker replied, we have ways to blind him. But all the same she sat in the furthest, darkest corner, under the screen showing the international cricket, hidden from any prying eyes, her ’hoek shut down and cold in her handbag.

So what are you finding out? she asked.

It would be more than my job is worth to tell you, Mrs. Rathore, said the Krishna Cop. National security. Then the waiter brought coffee on a silver tray.

After that they never went back to the office. On the days of their meetings Thacker would whirl her through the city in his government car to Chandni Chowk, to Humayun’s Tomb and the Qutb Minar, even to the Shalimar Gardens. Esha knew what he was doing, taking her to those same places where her husband had enchanted her. How closely have you been watching me? she thought. Are you trying to seduce me? For Thacker did not magic her away to the eight Delhis of the dead past, but immersed her in the crowd, the smell, the bustle, the voices and commerce and traffic and music; her present, her city burning with life and movement. I was fading, she realized. Fading out of the world, becoming a ghost, locked in that invisible marriage, just the two of us, seen and unseen, always together, only together. She would feel for the plastic fetus of her ’hoek coiled in the bottom of her jeweled bag and hate it a little. When she slipped it back behind her ear in the privacy of the phatphat back to her bungalow, she would remember that Thacker was always assiduous in thanking her for her help in national security. Her reply was always the same: Never thank a woman for betraying her husband over her country.

He would ask, of course. Out and about, she would say. Sometimes I just need to get out of this place, get away. Yes, even from you. . . . Holding the words, the look into the eye of the lens just long enough. . . .

Yes, of course, you must.

Now the earthmovers had turned Kunda Khadar into Asia’s largest construction site, the negotiations entered a new stage. Varanasi was talking directly to Washington to put pressure on Awadh to abandon the dam and avoid a potentially destabilizing water war. US support was conditional on Bharat’s agreement to the Hamilton protocols, which Bharat could never do, not with its major international revenue generator being the wholly aeai-generated soapi Town and Country.

Washington telling me to effectively sign my own death warrant, A.J. Rao would laugh. Americans surely appreciate irony. All this he told her as they sat on the well-tended lawn sipping green chai through a straw, Esha sweating freely in the swelter but unwilling to go into the air-conditioned cool because she knew there were still paparazzi lenses out there, focusing. AyJay never needed to sweat. But she still knew that he split himself. In the night, in the rare cool, he would ask, dance for me. But she didn’t dance any more, not for aeai A.J. Rao, not for Pranh, not for a thrilled audience who would shower her with praise and flowers and money and fame. Not even for herself.

Tired. Too tired. The heat. Too tired.

Thacker is on edge, toying with his chai cup, wary of eye contact when they meet in his beloved International Coffee House. He takes her hand and draws the updates into her open palm with boyish coyness. His talk is smaller than small, finicky, itchily polite. Finally, he dares looks at her.

“Mrs. Rathore, I have something I must ask you. I have wanted to ask you for some time now.”

Always, the name, the honorific. But the breath still freezes, her heart kicks in animal fear.

“You know you can ask me anything.” Tastes like poison. Thacker can’t hold her eye, ducks away, Killa Krishna Kop turned shy boy.

“Mrs. Rathore, I am wondering if you would like to come and see me play cricket?”

The Department of Artificial Intelligence Registration and Licensing versus Parks and Cemeteries Service of Delhi is hardly a Test against the United States of Bengal, but it is still enough of a social occasion to out posh frocks and Number One saris. Pavilions, parasols, sunshades ring the scorched grass of the Civil Service of Awadh sports ground, a flock of white wings. Those who can afford portable airco field generators sit in the cool drinking English Pimms Number 1 Cup. The rest fan themselves. Incognito in hi-label shades and light silk dupatta, Esha Rathore looks at the salt white figures moving on the circle of brown grass and wonders what it is they find so important in their game of sticks and ball to make themselves suffer so.

She had felt hideously self-conscious when she slipped out of the phatphat in her flimsy disguise. Then as she saw the crowds in their mela finery milling and chatting, heat rose inside her, the same energy that allowed her to hide behind her performances, seen but unseen. A face half the country sees on its morning chati mags, yet can vanish so easily under shades and a headscarf. Slum features. The anonymity of the basti bred into the cheekbones, a face from the great crowd.

The Krishna Cops have been put in to bat by Parks and Cemeteries. Thacker is in the middle of the batting order, but Parks and Cemeteries pace bowler Chaudry and the lumpy wicket is making short work of the Department’s openers. One on his way to the painted wooden pavilion, and Thacker striding toward the crease, pulling on his gloves, taking his place, lining up his bat. He is very handsome in his whites, Esha thinks. He runs a couple of desultory ones with his partner at the other end, then it’s; a new over. Clop of ball on willow. A rich, sweet sound. A couple of safe returns. Then the bowler lines and brings his arm round in a windmill. The ball gets a sweet mad bounce. Thacker fixes it with his eye, steps back, takes it in the middle of the bat and drives it down, hard, fast, bounding toward the boundary rope that kicks it into the air for a cheer and a flurry of applause and a four. And Esha is on her feet, hands raised to applaud, cheering. The score clicks over on the big board, and she is still on her feet, alone of all the audience. For directly across the ground, in front of the sight screens, is a tall, elegant figure in black, wearing a red turban.

Him. Impossibly, him. Looking right at her, through the white-clad players as if they were ghosts. And very slowly, he lifts a finger and taps it to his right ear.

She knows what she’ll find but she must raise her fingers in echo, feel with horror the coil of plastic overlooked i

n her excitement to get to the game, nestled accusing in her hair like a snake.

“So, who won the cricket then?”

“Why do you need to ask me? If it were important to you, you’d know. Like you can know anything you really want to.”

“You don’t know? Didn’t you stay to the end? I thought the point of sport was who won. What other reason would you have to follow intra-Civil Service cricket?”

If Puri the maid were to walk into the living room, she would see a scene from a folk tale: a woman shouting and raging at silent dead air. But Puri does her duties and leaves as soon as she can. She’s not at ease in a house of djinns.

‘“Sarcasm is it now? Where did you learn that? Some sarcasm aeai you’ve made part of yourself? So now there’s another part of you I don’t know, that I’m supposed to love? Well, I don’t like it and I won’t love it because it makes you look petty and mean and spiteful.”

“There are no aeais for that. We have no need for those emotions. If I learned these, I learned them from humans.”

Esha lifts her hand to rip away the ’hoek, hurl it against the wall.

“No!”

So far Rao has been voice-only, now the slanting late-afternoon golden light stirs and curdles into the body of her husband.

“Don’t,” he says. “Don’t . . . banish me. I do love you.”

“What does that mean?” Esha screams “You’re not real! None of this is real! It’s just a story we made up because we wanted to believe it. Other people, they have real marriages, real lives, real sex. Real . . . children.”

“Children. Is that what it is? I thought the fame, the attention was the thing, that there never would be children to ruin your career and your body. But if that’s no longer enough, we can have children, the best children I can buy.”

Esha cries out, a keen of disappointment and frustration. The neighbors will hear. But the neighbors have been hearing everything, listening, gossiping. No secrets in the city of djinns.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

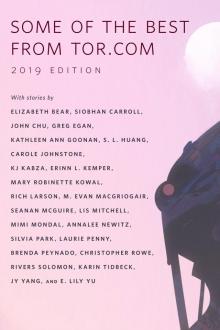

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3