- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

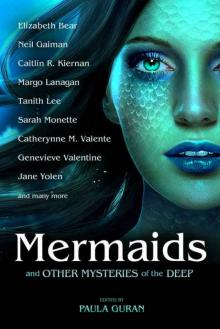

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep Page 2

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep Read online

Page 2

You fish a miniature Maglite out of your pocket and shine it through a grimed louvered window, though you already suspect what you’re going to see inside. Boxes, torn and water stained. Mouse droppings. Blown leaves curled like brown dead spiders. There are footprints in the dirt on the boards, but they stop right inside the door and turn around.

A ghost-story chill chases around your shoulders, or maybe that’s just the wind sneaking between your scarf and your hat. Deep in the woods, the metallic call of a cardinal blurs through naked branches: wheet, wheet, chipchipchipchipchipchip. Nobody lives here, and hasn’t in years.

You catch yourself looking over your shoulder and shake your head. No one is sneaking up behind you and you’d be sure to hear them crunching if they were. Still, when you step back from the window, you hunch your shoulders at more than the cold.

The trail leads around the left side of the house. You stuff your gloved hands into your coat pockets and rub the sleek case of your cellphone with leathered fingertips. You’d call 911, but what would you tell them? I dropped a girl off here late last night and I’m not sure she was really blind? You’re not even sure if she was really here.

If you call, you won’t have to find what you might find in a snowdrift. But then if you call and there’s nothing, what will that look like? Better to go check for yourself, just to make sure.

Maybe somebody was waiting here for her. There’s the other set of footprints. Maybe there’s a carriage house around back, an in-law apartment or something, and that’s where people live.

Sniffing deeply, you can imagine you smell wood smoke. But when you come around the corner into the back yard, there’s nothing but those two sets of tracks, still laid over one another, one big and one little. They cross the yard diagonally, past a trio of blueberry bushes in torn wire cages, and vanish among the trees. The snow is well-trampled, too: you don’t think these are the marks of only one passage, or even just a couple.

You glance over your shoulder again. Then, shoulders squared, eyes front, you start forward, whistling the jaunty cardinal’s song back at him.

You hope to see him flicker through the trees—red wings would be a welcome distraction from a world of white and black—but the only movement is the pall of your breath hung on the air, the way it curls to either side when you move through it. A hundred yards into the trees, just the other side of a snowy scramble over a humped stone wall that must once have marked a field boundary, the paths diverge—larger booted footsteps back towards the road, smaller sneakers deeper into the wood.

“Two roads diverged in a snowy wood,” you mutter, conflating two poems, but Frost isn’t here to correct your misquotation and furthermore, it amuses you. The problem is, neither of them looks particularly less-traveled. But you’re guessing that the smaller feet must be Aisling’s, which means you should go that way. Deeper into the woods, in the fading afternoon.

Well, if it gets dark, you have a flashlight.

The wool socks and your insulated boots keep your toes warm, so when they start to hurt it’s just from walking downhill and getting jammed up against the front of the boots. The slope turns into a hill, and at the bottom of the hill you spot a broad swift brook, running narrow now between ice-gnarled stony banks. The chatter of the water against stone reaches you along with the smell.

Somebody told you once that ice and water don’t smell. When the scent of this fills you up, you wonder if their nose was broken. It’s clean and sharp and somehow, counterintuitively, earthy. Rich. Satisfying.

Aisling’s trail—if it is Aisling’s trail—ends at the ice.

“Shit!” You slalom down the slope, though there’s no point in hurrying. Whatever happened here happened hours ago, and there’s no sign of Aisling. Her footprints vanish when they reach the stream.

There’s an obvious course of action. Wool socks will keep your feet warm even wet, your boots are reasonably waterproof, and it’ll be safer to splash through the water than try to walk on the icy rocks. As you teeter into the brook, arms outstretched, an icy gout leaps up inside the leg of your jeans. You’d shriek, but the cold is so intense it’s silencing.

You’re committed now. You turn upstream, at a guess, because a guess is all you have. Some other bird is singing now, something more flutelike and complicated than the cardinal, and it seems to come from this direction. Under the circumstances, music seems as good a guide as any.

You’re still trying to decide if you’ve chosen the right direction when the brook vanishes among jumbled boulders into the side of the hill.

“Well, fuck,” you say. Water can go where you can’t. Downstream, then, you think, and turn.

The music is coming from out of the ground. An acoustic illusion, some trick of how sound conducts around the stones. But you turn back nonetheless, unable to resist the lure of a mystery, and inch closer to the stones. Wool socks or not, your toes numb in their boots. Despite that, when you kick a rock by accident, the pain spikes to your knee.

When you put a hand on the rocks and lean into the gap, the echoes tell you where it goes. The entrance is tight, but you could squeeze through without stripping. The rock under your hand tells you something else, too: it’s a known cave, one with regular visitors. The stone is polished as if in a tumbler, rubbed smooth by many years of passages, the wear of cloth against stone.

You grope in your pocket for the light, twist it on. The floor’s all mud within, frozen and sticky, but you can see a trail down the corridor where someone’s crunched through surface ice into the muck beneath.

Inside, the singing reverberates. There’s no mistaking it now: it’s a human voice, distorted by resonances, rippling with overtones and echoes. And it’s singing one of your songs.

Your heart squeezes so hard it chokes you, a triphammer beat of relief and excitement and fear. You have to clear your throat twice to speak, but when you get your voice unstuck you shape a breath and call out “Aisling?”

The singing stops, but the echoes trail, complexifying before they die. Away in the cave you hear a splash, and that echoes too.

“Aisling? I have a light. Talk to me, so I can find you?”

There’s a pause, when you expected hysterical calls for help. And then she says, “I’m back where the water is. Come and find me.”

You follow the stream again, this time through the muddy deposits and then over clean stones. Your light skitters over gray and black and pale, streaks and circles, and some of that must be fossils because you don’t think stones grow in those shapes. You’ve always heard that the dark in a cave is supposed to be oppressive, that the weight of stone over your head should press you down. But it’s peaceful here, quiet and sweet, calm as a cathedral. The water rings on stone like a Zen fountain, and Aisling sings harmonies around it to guide you.

The deeper into the cave you get, the warmer the air becomes. Not warm, actually, but no longer freezing either. The mud underfoot stops crunching, and when the stream drops off sharply you step out of the flow and onto the well-worn trail beside it.

When you step on the bra, you almost drop your light.

It’s a black bra, the stiff seamless under-a-T-shirt kind, and piled beside it, soaked on the cave floor, are white panties and a thin blue T-shirt. No jeans and no shoes. Sometimes, don’t people get crazy with hypothermia and take off their clothes because they think they’re dying of heat when they’re already freezing?

“Aisling?”

“Down here,” she says. “In the water.”

You shine the light down, to where the cave opens away from a winding braided channel and becomes something like a room. Its rays reflect from a rippled surface, the limpid waters of an underground lake, so transparent that even with the flashlight glare you can see the weird white limestone structures that hump and glide across its bottom. And you can see Aisling in the water, through the water, her colorless hair all around her like seaweed, teacup breasts white as the rock she floats over, the featureless flesh where he

r eyes should be, the wide slash of her lipless mouth, and the ragged plumy sweep of her long, light-scattering tail.

“You’re a mermaid,” you say, as if it were the most natural thing in the world. Listening to your own level voice shocks you more, right now, than Aisling does. “You’re a mermaid in a cave.”

“Very good,” she tells you, her voice a reedy, layered thing. “Most people are much worse about denying the evidence of their eyes. Come on in, my darling. The water’s fine.”

The water, in point of fact, is freezing, or very nearly so. Ice crystals brush your naked arms and legs, the water sucking heat from your liver and ovaries. You start to shiver before you’re even fully immersed, a bone-rattling chill that makes you fear for your tongue should you attempt to speak. And yet you still walk to her, until the cave water laps your collarbones like desperate tongues, until the finny spikes of her webbed outreached fingertips scratch the calluses on your own.

The flashlight, left propped on a stone, spreads sallow light around the cave, inadequate to touch its corners. The blind mermaid still seems clearly delineated, as if she collected light or as if some inner light illuminated her. Maybe mermaids are bioluminescent. Maybe nobody’s ever done the research.

Don’t be an idiot. The research?

Her knobbled-slick hands close on your wrists and she draws you into water so cold you can’t feel it, can’t really feel the moment when your feet lose contact with the knobbled-slick limestone floor. Her brawny tail pries between your legs, fish-slippery, hard muscle rasping-rough with the scales that sparkled. Fins hook your ankles, glass-sharp on knobby bone, and her hands glide wide on your scapulae, so you can feel the prickle of their roughness and also the way your bony edges press into her palms. She has breasts, and why on earth would a mermaid have milk and mammal breasts when she is so obviously not a mammal? But there they are, floating against your own, nipples as hard and white as the rest of her.

When she kisses you on the mouth you feel the prick of all her sharp sharp teeth. You kiss her back, eyes drifting closed, shivering so hard you barely find her mouth, and her best of voices whispers, “Open your eyes.”

You do, and see the dim light glitter on the cave roof as she floats you. The cold is sinking deep, deep into your meat and organs, so you shake already like a woman in orgasm.

The blind mermaid doesn’t care. You put your hands in the dilute cloud of her hair, so she pulls against your grip as she kisses down your throat—leaving rings of pinpricks on your collarbone—down the slopes of your breasts until you grind against her strong uncooperative body, arching back, crying out.

She scrapes your belly like rough stone, her hands pressing the small of your back up to hold your face in air. She hums to you as she kisses until you could drown here, drown in her voice, drown in this desperate cold and die happy. Water falls from the cave roof, strikes your mouth and eyes. You imagine the stalactites it’s forming, each single droplet a force for legacy.

“Sing for me,” she says, half-underwater. Her lips scrape the skin over your hip ridge until you whine. She likes to kiss where the bones come up under the surface of your body like gliding fish. “Sing for me, or I kiss no more.”

“Cold,” you manage, though it falls from you like a whisper. Your teeth aren’t knocking themselves to pieces in your head anymore. You think that means you’re dying: that your body won’t shiver any more.

“Sing,” she says, with a flicker of her tongue that—cold or not—makes you cry.

So you sing in the mermaid’s arms, in whispers and tiny sharp gasps of breath that blues your lips with cold, expecting her touch will be your death and not caring, for the beauty of the frozen song.

You awaken stiff and alone with your scrapes and bruises, when you expected not to awaken at all. Someone has heaped stained cloth and a torn old sleeping bag under and over you. In sleep you’ve curled tight as a grub, your abdominal muscles aching with contraction. There’s light: it must be the next morning.

You hope it’s only the next morning. When you lift your head, you realize that you’re not in the cave any longer.

You lie on a plywood floor before the soot-stained brick pad that supports a cast-iron woodstove. The walls are peeling metal and seem very close to either side and from about waist-height they’re mostly made of rows of windows, as if you were in an airplane fuselage. The windows are covered in a layer of transparent plastic, condensation misting the enclosed side and turning to frost on the metal-framed windows.

That woodstove ripples with heat. Radiant energy flattens against your face, picking moisture from your cheeks and eyelids. You turn from it and try to find the strength to roll away, but your arms won’t move you, so you pull the edge of the sleeping bag up as a shield instead, and assess the damage.

Your skin burns everywhere she kissed you, swollen in chilblains red as lipstick prints. They smart when you press them, though your fingertips are cold enough that all you can feel is how much they hurt when you touch anything.

The plywood shudders with footsteps, and this time the adrenaline gives you enough energy to sit. Half-sit, anyway, slumped forward on locked elbows with your hair draggled in your eyes like a shipwrecked survivor pushing herself out up from the surf. You feel castaway, cast-off. Sea-wracked and adrift, or maybe fetched up hard against the rocks and dashed there.

“Oh, good,” a voice says, too loud. “You lived. Don’t bother talking until you can look at me. Save your strength, ’cause I can’t hear you.”

You get your head up as he squats down, scarred boots laced only partway and the ragged cuffs of his dungarees spattered with salt and mud and (mostly) sawdust. He’s a white guy, hair gray and thinning on top and not long. His cheeks were clean-shaven about three days ago: now silver hairs sparkle against dull skin. He’s not a big guy and he’s not a young guy, and even though he’s dirty and ragged and you’re naked on the floor under a pile of rags he doesn’t make you scared. You wonder if you’ll ever feel scared again, after the cave, after the mermaid inside it.

He tugs the sleeping bag up over your shoulders with a rough-skinned hand and steps back. “I’ll get you some coffee,” he says. “And some clothes.”

By the time he comes back with a flannel shirt, T-shirt, cardigan, and too-big men’s jeans washed soft, you’ve managed to edge away from the crisping heat of the woodstove and get yourself wedged into a ladderback chair. An enamel pan sits atop the stove, steam rising from the water that must be simmering inside, but you can’t tell that it’s making any difference to the humidity. A few steps away from the stove, you can feel the baffling cold seeping through the metal walls of what you know realize is an ancient school bus, probably up on blocks and definitely not in any condition to ever go anywhere again, because from here you can see the holes in the firewall where the steering column and gearshift used to go.

He leaves the clothes and turns his back, except you’re not sure you can get the pants on by yourself. You’d call him, but you don’t know his name, and after you say “Hey!” a couple of times you remember what he said about not being able to hear, and how loud he spoke.

Well, you made it into the chair. You can probably make it into the trousers.

With a little help from the chair you do. You’re pulling the flannel shirt over the T-shirt when he comes back with a big blue plastic travel mug with a gas station logo on the side. It steams when he gives it over. Some of the warmth within seeps through the empty spaces between its inner and outer walls and stings your hands, but you cup it close anyway. It’s white, which makes it cool enough to drink, and you don’t stop until you’ve drained it to the bottom. It tastes like oily vanilla creamer and boiled coffee grounds and enough sugar to make your teeth ache and leave grit on your tongue and at the bottom of the cup, which right this second makes it the best thing you’ve ever tasted.

When you hand the cup back to the man, he fills it up from a thermos that sits on a knocked-together wood table along one side of

the school bus. He must sleep underneath it, because a cot mattress is just visible behind the curtains tacked up to its underside. The second mug of coffee, you cradle between your palms and savor, and when he’s looking at your mouth you say “Thank you.”

Your voice startles you a little. Maybe it’s the cold stopping up your ears, but it sounds plummier and more resonant than it should.

“T’ain’t nothing,” he says, and grins. “You’re not the first one to meet the girl in the cave and come off worse—and better—for it.” He touches his ear. “I can’t hear her singing anymore, but I keep an eye out for anybody else who does.”

“Are there a lot of us?”

He shrugs. “Every five, ten years or so. It’s been a while since the last one. You’ll probably more or less recover, given time.”

“More or less?” You swallow more coffee, scrub the sweet sand of sugar across your palate with your tongue.

“Don’t expect you won’t be changed. By the way, I’m Marty.”

“I’m Missy,” you say, which is what your mom called you when she wasn’t mad. You nerve yourself, as if bracing against some cold that’s inside you, and say, “She’s under my skin.”

“She gets there,” he says. “What are you going to do about it?”

You shrug. He hands you a pair of wool socks—your own socks, washed out and damp still.

“I’ve got some work,” he says. “You’re welcome to stay in here until you feel well enough to go. There’s soup in the cupboard. You can heat it on the stove if you want.”

He points, tins in a series of stacked Guida Dairy crates. You see Progresso lentil, Campbell’s clam chowder. Boxes of crackers stuffed inside plastic freezer bags so the mice don’t smell them.

“Thanks,” you say. “I’m good. What kind of work?”

“Excuse me?”

“Your work,” you say. “What kind of work do you do?”

“Oh.” He stares down at his hands. “I make dulcimers and stuff.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

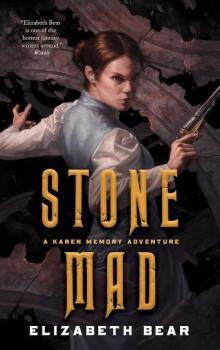

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

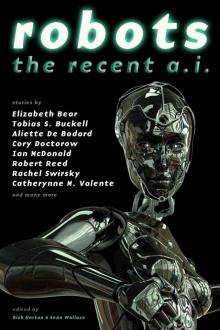

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

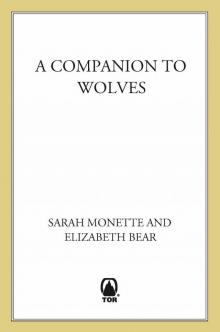

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

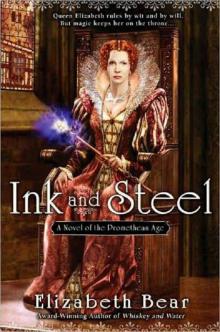

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3