- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Worldwired Page 2

Worldwired Read online

Page 2

“Hi, Fred. I was at lunch,” Constance Riel said, chewing, her image flickering in the cheap holographic display. Valens smoothed the interface plate, cool plastic slightly tacky and gritty with the omnipresent dust. The prime minister covered her mouth with the back of her left hand and swallowed, set her sandwich down on a napkin, reached for her coffee. Careful makeup could not hide the hollows under her eyes, dark as thumbprints. “I was going to call you today anyway. How's the Evac?”

“Stable.” One word, soaked in exhaustion. “I got mail from Elspeth Dunsany today. She says the commonwealth scientists have arrived safely on the Montreal. One Australian and an expat Brit. She and Casey are getting them settled.”

“Paul Perry said the same thing to me this morning,” Riel answered. Her head wobbled when she nodded.

“That isn't why you were going to call me.”

“No. I have the latest climatological data from Richard and Alan. The AIs say that the nanite propagation is going well, despite the effects of the—”

“Nuclear winter? Non-nuclear winter?” Valens said.

“Something like that. They're concerned about the algae die off we were experiencing before the Impact. More algae means less CO2 left in the atmosphere, which means less greenhouse warming when the dust is out of the atmosphere and winter finally ends—”

“—in eighteen months or so. Won't we want a greenhouse effect then?” To counteract the global dimming from the dust.

“Not unless 50° or 60°C is your idea of comfort.”

Valens shook his head, looking down at the pink and green displays that hovered under the surface of the interface plate, awaiting a touch to bring them to multidimensionality. He shook his head and ricocheted uncomfortably to the topic that was the reason for his call. “We've done what we can here. It's time to close up shop. Do you want to tour the exclusion zone?”

“Helicopter tour,” she said, nodding, and took another bite of her sandwich. “You'll come with, of course. Before we open the Evac to reconstruction and send the bulldozers in.”

“You're going to rebuild Toronto?” Valens had years of practice keeping shock out of his voice. He failed utterly, his gut coiling at something that struck him as plain obscenity.

“No,” she said. “We're going to turn it into a park. By the way, are you resigning your commission?”

Valens coughed. Riel's image flickered as the interface panel, released from the pressure of his palm, wrinkled again. “Am I being asked to?”

The prime minister laughed. “You're being asked to get your ass to the provisional capital of Vancouver, Fred. Where, in recognition of your exemplary service handling the Toronto Evac relief effort, you will be promoted to Brigadier General Frederick Valens, and I will have a brand-new shiny cabinet title and a whole new ration of shit to hand you, sir.”

“I'm a Conservative, Connie.”

“That's okay,” she answered. “You can switch.”

HMCSS Montreal, Earth orbit

Thursday September 27, 2063

After dinner

Elspeth touched the corner of her mouth with her napkin, careful of the unaccustomed weight of lipstick. She leaned a shoulder against Jen Casey's upper arm and nudged, the steel armature hard under the rifle-green wool of Jenny's dress uniform. Jen's glass of grapefruit juice clicked against her teeth. She shot Elspeth a tolerant glance. “Doc—”

“Sorry.”

In present company, it wouldn't do for Jen to drop that steel arm around Elspeth's shoulders and give her a hard, infinitely careful hug, but she managed to make her answering jostle almost as comforting.

They had moved into the captain's reception hall after dinner, and Captain Wainwright herself was propping up a wall in the corner by the room's two big ports. It was too cold for Elspeth's taste, that close to the glass, and she'd joined Jen in her relentless stakeout of the nibbles-and-dessert table. Both Jeremy Kirkpatrick—the commonwealth ethnolinguist—and Dr. Tjakamarra were sticking close to the windows, although Elspeth could tell the Australian was shivering. He stood hunched like a worried cat, his arms folded over each other, and divided his attention between Jaime Wainwright and Gabe Castaign, whose hulking presence manned the canapé bucket brigade for the newcomers, in courtesy to their temporary role as distinguished guests. The ecologist Paul Perry—long-fingered, slight, and dark—almost disappeared behind Charles Forster, a paunchy xenobiologist with his vanishing hair shaved close to a shiny scalp. One little, two little, three little Indians. Or should that be we few, we happy few, we band of brothers?

Five scientists, a programmer, a pilot, and an artificial intelligence. And a partridge in a pear tree. And the biggest scientific puzzle of the century.

You've come a bit far for a bout of impostor syndrome, El.

“What do you think of the new kids?” Jen said, dropping her half-full glass on a passing tray with a grimace of distaste.

“They made it through the rubber-chicken dinner with a minimum of fuss.” The tilt of Elspeth's head indicated the mess hall on the other side of one of Montreal's few irising doors.

“Especially since it was rubber tofu.” Jen grinned, that wry mocking twist of her mouth that was as contagious as the common cold, and Elspeth had to grin back. “I haven't had a chance to talk to Kirkpatrick yet, but the Australian's all right.” She shrugged. “My heart's not in it, Doc—”

“No.” Elspeth reached for a drink herself, tomato juice and a stalk of celery, wishing there were less Virgin and more Bloody in it. “I don't think any of our hearts are in it, after last Christmas.” After Toronto. “But it's got to be done. They scare me.” She tipped her head to indicate the long ornate outline of the shiptree, visible beyond the port, winking lights and elegant curves like hand-smoothed wood. “And Richard says Fred says something has to break on the PanChinese front shortly. Riel's going to demand restitution for Toronto—”

“She wants to get Richard admitted as a witness.”

“Right. And there's that Chinese pilot, the one who tried to prevent the attack—”

“He's safe at Lake Simcoe,” Jen said, her voice dripping mockery. Both she and Elspeth had a longstanding acquaintance with the high-security military prison there. “Protective custody.” She cocked her head, that listening gesture that told Elspeth—to Elspeth's infinite frustration—that she was talking to Richard.

Their eyes met for a moment, a shared frown. “You heard that Fred is Brigadier General Fred as of this afternoon, I assume?”

The irony in Jen's expression made her eyes glitter like a bird's. “Richard says to let him and Fred and Riel handle Earth and China, and worry about talking to the Benefactors.” Jen swallowed and glanced about for the drink she'd discarded. Thwarted, she shoved her hand into the pocket of her uniform.

“Can't we worry about everything at once?” Elspeth wandered toward the snack table, Jen trailing, and picked up a plate. She started loading it with canapés, inspecting each one.

“Richard says it might not be a bad idea to have figured out how to talk to the Benefactors by the time the PanChinese start shooting at us again. If they start shooting at us again. In case the Benefactors take that as evidence that the hairless apes are too uppity to be permitted to roam the universe at large, and decide to do something permanent about us.”

“Richard is a bloodthirsty son of a bitch.” Elspeth bit a cracker in half and chewed in an unladylike fashion. So much for the lipstick. I need to get VR implants at least. She hated not being able to listen to Richard directly, the way that Jenny and Patricia Valens, the Montreal's apprentice pilot, could. “Very well. ‘We cannot weep for the whole world.' I guess we hold up our end of the table and trust in Fred to hold up his. We'll have a summit meeting tomorrow, us two and Gabe and Charlie and Paul and the new kids. And Dick, onscreen so everybody can talk to him.” She swallowed the other half of the canapé, cracker corners scratching her throat. “What're you doing for your birthday?”

“Birthday?”<

br />

“Sunday? The day you turn fifty-one?”

“Don't remind me—”

Elspeth grinned. “Okay, I won't. Gabe and I will plan something. It'll be just us and Genie.” Her voice wanted to hitch on Genie's name; it wasn't supposed to be just Genie. It was supposed to be Genie-and-Leah, but the second name hung between them, chronically unsaid. Elspeth brushed it aside with the back of her hand. “You just promise to show up and be a good sport.”

Jen's expression warred between resignation, delight, and trepidation. Finally, she nodded and studied the carpeted floor, scrubbing her gloved iron hand against her flesh one as if dusting away a fistful of crumbs. “Patty,” she said. “Patty Valens. Invite her, too? She's all alone up here—”

“More than fair.” Elspeth's hesitation was strong enough that Jen looked up and frowned, meeting her gaze directly.

“What?”

“This meeting tomorrow—”

“Yes?”

“Is it too much to ask for you to brainstorm and come up with something we can do to get the Benefactors' interest, other than balancing our checkbooks back and forth at each other?”

Jen laughed dryly. “I've got an idea you're going to love, if Wainwright doesn't shoot me for suggesting it.”

“Well, don't leave me hanging.”

Genevieve Casey arched her long neck back, stared at the ceiling, laced her hands together in front of her, and said with studied casualness, “I want to find out what happens if we EVA over to the birdcage and wander around inside.”

Thursday 27 September 2063

HMCSS Montreal processor core

HMCSS Calgary processor core

Whole-Earth Benefactor nanonetwork (worldwire)

21:28:28:35–21:43:28:39

When Dick took over the planet, he'd been prepared for surprises. But the ache of the Toronto Evac Zone like a runner's stitch in his side had not been one of them.

He'd comprehended the scale of the damage, of course; of all the sentiences in his sphere of experience, he was uniquely qualified to do so. He'd understood that the global nanotech infection that Leah Castaign and Trevor Koske had given their lives to engender would be a mitigating factor at best, and not even the temporary magic bullet of a penicillin cure. He'd thought he understood what spreading his consciousness through a planet-sized, quantum-connected worldwire would entail. If he could call it his consciousness anymore, as he evolved from a discrete intelligence into a multithreaded entity that might be compared to a human with disassociative identity disorder—

—if such a disorder were a native state of affairs, and if the various personalities carried on a constant, raucous, and very rarified debate regarding every serious action they undertook. If portions of that entity brushed feather-light fingertips across the waking and sleeping minds of certain augmented humans, and other portions moved through the ruined waters of Lake Ontario, and hovered in the well-shielded brain of Her Majesty's Canadian starship Calgary in its position of rest at the bottom of the ocean; if other portions infected fish and birds and bushes and topsoil and atmosphere, and extended like a meat intelligence's subconscious through eleven-dimensional space and into the alien nanotools of the far-flung Benefactor empire, or confederacy, or kinship system—or whatever the hell it might be, Richard mused, with the fragment of himself that never stopped musing on such things. If.

I never began to imagine what I was in for, he thought, shifting focus as Constance Riel touched her earpiece and accepted his call. She wasn't in her temporary office in the provisional capitol, but a mobile one aboard her customized airliner. “Good evening, Dr. Feynman.”

“The same to you, Prime Minister. I understand that you will be touring the Evac with Dr. Valens tomorrow.”

“Preparatory to closing the relief effort, yes. I'm on my way there now. And on behalf of the Canadian people”—she leaned forward—“I want to formally thank you for your efforts. Which I am about to ask you to redouble.”

“Restoring the Evac is a lower priority than mitigating the climatic damage, you realize.”

A quick, dismissive flip of her hand reinforced her curt nod of agreement. “We have an official complaint on record from the PanChinese ambassador to the Netherlands, by the way. It seems he's attempting to get the nanotech infestation classed as an invasion of the sovereign territory of the PanChinese Alliance, and get it heard by the International Court of Justice.”

“You don't sound displeased.”

Riel grinned wolfishly. “We can't bring our suit for attempted genocide unless they consent to be a party to the case. Which they just did, more or less—or we can spin it so they did. Of course, Premier Xiong can't put up much of a fight, since he's still pretending the attack was the work of fringe elements.”

“If Premier Xiong was not privy to the attack, he may have a coup on his hands before too much longer. My analysis—which is based on severely inadequate data, and the preliminary testimony of Pilot Xie—is that the orders to attack must have come from high up in the PanChinese government.”

“I agree. Unfortunately, there's not much I can do about that currently. In a more immediate concern, though, World Health is on my ass again. We need a policy on use of your nanotech in medical emergencies.”

Richard sighed, pushing aside the “itch” that was the infestation's response to the damage surrounding the Impact. Life-threatening conditions first. Superficial wounds, no matter how unsightly, can wait. “This whole thing is a moral—”

“Quandary?”

“Quagmire.” He shrugged, hands opened broadly in one of the little gestures he'd inherited from the human subject his personality was modeled on. “I've got 60 percent global coverage right now and growing, and we used the nanosurgeons successfully on a few of the worst-injured Impact victims—and unsuccessfully on a whole lot more—but I've got extensive climatic damage to consider. I'm expecting mass extinctions, once the field biologists get some hard data back to us, and another spike in dieoffs once the dust clears and the temperature increase starts. Practically speaking, we can get a certain amount of the carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere before then, but not enough to prevent the damage. We're talking mitigation at best, and we should expect a much warmer global climate overall.”

“How much warmer?”

“Think dinosaurs tromping through steamy tropical forests, and shallow inland seas. And wild weather. Also, we should expect earthquakes as the polar ice melts. It's heavy, you know—”

“These are all secondary concerns, aren't they?”

“Not in the long term.”

“They sound infinitely better than that snowball Earth you and Paul were talking about last year. Look, tell me about your moral quagmire first. The climate issues are easy; we mitigate as much as we can, and whatever we can't, we suck up. I'm worried about the personal cost.”

A moment of silent understanding passed between them, intermediated by the technology that permitted them to look eye-to-eye. Riel glanced down first. Since Richard's image floated in her contact lens, it didn't break the connection. “I'm tempted to tell you to restrict the damned nanosurgeons from PanChinese territory. But then they would claim we were sabotaging their environmental efforts and failing to make resources freely available on an equal basis . . . It's a mess, Dick. And once we move Canada off a crisis footing, smaller wolves than China are going to be sniffing about for a piece of the corpse as well. Russia and the EU have provided aid; it's not like I'm in a position to turn them away—” She choked off, shaking her head. “I love my job. I just keep telling myself that I wouldn't rather be doing anything else in the world.”

A shared grin, and Richard cleared his throat and hesitated—another simulation of human behavior. Most of the humans were more comfortable with him, rather than Alan—the only other AI persona who had had significant interpersonal contact. In fact, most of the humans had no idea the rest of the threaded personalities existed, yet.

Richard had never been o

ne to spoil a surprise. “The least complex solution would be to prepare a contract and ask any country that wishes my intervention to sign it.”

“What are we going to do about sick people who wish to volunteer for nanosurgical treatment?”

“We'll have to let them volunteer,” Richard answered. “We've already used the nanites on Canadians in a widespread fashion. It would be . . . inhumane to restrict the benefits to your own citizens. But the volunteers will need to be apprised of the risks, which are significant.”

“Ever the master of understatement.” She pressed a fountain pen between her lips absently, sucking on the gold-plated barrel. Richard quelled the irrational—and impossible—urge to reach out and take it out of her mouth. “The promise of free medical treatment will open some borders. What about the nations that demand access to the augmentation program?”

“Military applications of technology have always been handled differently than medical ones.”

“Touché. People will scream.”

“People are screaming. This isn't magic, Prime Minister.”

“No,” she said, leaning back in her chair. “Just something that will look like magic to desperate people, and they'll be angry when it doesn't work like magic, won't they? Oh, that reminds me. I'd like to keep as many people—commonwealth citizens and otherwise—uninfected as possible.”

“Most people are going to encounter a life-threatening incident sooner or later.” But that wasn't disagreement. She was right; they didn't know what the Benefactors were capable of, or what they wanted, and it was their technology with which Richard had so cavalierly infected the planet.

It seemed like a good idea at the time.

And cavalier wasn't a good word, though the process had been less cautiously handled than Richard would have preferred.

Less cautiously handled than Riel would have preferred, too, and she was talking again. “Most people are. Some will refuse treatment. Some won't need treatment. It's a unique situation; this stuff is loose in the ecosystem, but unlike every other contaminant in history, we have perfect control over it.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

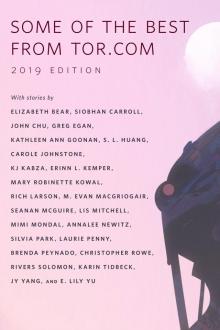

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

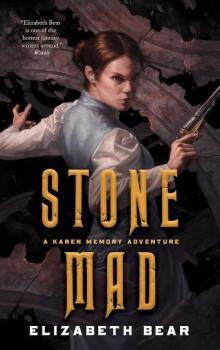

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3