- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

A Companion to Wolves Page 20

A Companion to Wolves Read online

Page 20

Isolfr nodded, and tried his voice again. This time, the words were recognizable, if harsh. “Is everyone—”

“No one’s died,” Sokkolfr said, settling beside him. “Ulfrikr’s nose set crooked from where you hit him, though. He breathes with a whistle now. I didn’t think you’d be upset.” He shaded his mouth with his hand. “No one else is, except his shieldmates, for the snoring.”

Isolfr found a smile somewhere. It hurt his mouth, but he stuck with it, and in a minute it got easier. “I feel awful.”

“You look awful. Want to try some broth?”

Shockingly, his stomach rumbled. “Please?”

He didn’t miss the relief on Sokkolfr’s face, and it warmed him. “I’ll fetch it from Jorveig in a minute. Isolfr—”

“Yes?”

“Are you all right? I mean …” A sigh, and a helpless shrug, and that troubled, watchful spark deep in Sokkolfr’s eyes. It surprised and warmed Isolfr to see his friend’s care, even as Sokkolfr continued speaking. “I think even Hrolleif was worried, when you wouldn’t let Viradechtis near.”

Isolfr thought about it. He turned his head on his aching neck and looked the wolf in her unblinking yellow eyes. She whined low and reached out, tentatively, to nose his cheek. He could leave. It wasn’t often spoken of, but he could forswear the wolfheall, forswear the wolf, and leave the pack. It had been done before. Isolfr imagined it would be done again.

But he had chosen this; he had gone into it knowing what sacrifices might be demanded. And he had survived it.

He slid one hand out from under the blankets and fisted it in Viradechtis’ ruff, so she whined again and leaned into him. “I’ll live,” he said, and shivered. Then he looked at Sokkolfr and reached out and grabbed his hand too. “I’m glad you’re back,” he said, and squeezed hard.

Sokkolfr smiled at him, his rare, sweet smile, and said, “Let me fetch that broth.”

But it was Frithulf who brought it, Frithulf who helped him sit, who held the bowl when Isolfr’s shaking hands could not manage. Isolfr could not look at Frithulf, his own screams seeming to echo in his ears. Finally, Frithulf set the bowl aside and said, “Is it my face?”

“What?”

“You won’t look at me. Is it my face?”

“No!” Isolfr’s head came up at that; he turned to look at Frithulf squarely. The scars were ugly, and they were dragging Frithulf’s mouth out of true, but they did not matter and Isolfr was horrified that Frithulf would think they did. “How could you think … ?”

“You wouldn’t be the first,” Frithulf said. “Well, if it isn’t my hideous countenance, what is it?”

“You were right,” Isolfr said; his nerve failed him, and he looked away. “Weak as a girl.”

“Damn my cursed flapping tongue!” Frithulf said, with such vehemence that even Hroi’s ears pricked, and Kothran whined anxiously and licked the scarred side of Frithulf’s face. “Isolfr, as you love me, will you forget the stupid things I say?”

“But—”

“No.” Frithulf was glaring at him, daring him to argue. Isolfr shut his mouth and waited. “Clorulf and Ulfbjorn have told us … what they can. Do you think I’m like Ulfrikr, to mock at you for being in pain?”

“I don’t think you’re like Ulfrikr,” Isolfr said, shocked.

“Then stop expecting me to behave like him.” Frithulf’s face softened, and he reached out, very gently, to touch Isolfr’s face, where his own face was scarred. “You knew what was coming, and you did not turn away from it. That’s bravery, Isolfr, not weakness.” His smile was crooked with scarring, but it was still Frithulf’s smile, still as bright and wicked as a magpie’s saucy glance. “And did Sokkolfr tell you, Ulfrikr whistles when he breathes? I don’t think he’ll be so quick to taunt you as womanish again. Not now that he has a closer acquaintance with your womanish fists.”

Isolfr settled back, surprised to find that Viradechtis had arranged herself as a warm, pillowed chair. Her body eased his aches, and he suspected Jorveig had put some herb or root in the broth; warmth and a sort of numb fuzziness chased through his limbs. He sighed, and leaned his head back on his wolf’s warm flank, and asked, “How goes the war?”

And fell asleep while Frithulf was telling him.

Viradechtis made herself his shadow, even when he was able to rise from his blankets again and totter to the privy or the bathhouse on his own. She even came into the bathhouse with him, and the werthreat laughed and complained, but none of them asked him to make her leave.

Understanding that she was unhappy, he did not try.

It took time for the question to rise from her mind to his, from instinct and scent into words. Three days after he woke clearheaded, when he was sitting with Frithulf rewrapping axe leathers while Kothran dozed belly-up in the weak winter sunlight and Viradechtis paced the courtyard thoughtfully, the words were there, simple words, almost childish words: mating hurt you. It was more images than words even then, but it was as close as Viradechtis would ever or could ever come to speaking to him, as a man spoke to his friend.

It startled him. Shocked him. Trellwolves did not speak in words.

But she was Viradechtis, and she was not like other wolves.

Yes, Isolfr agreed, because there was no point in trying to lie.

She paced the length of the courtyard again, and he felt his answer sinking down into her understanding. Frithulf was telling him tales of Franangford, and he listened with half his mind while the other half waited for his sister’s response.

When it came, it shocked him into dropping the axe hilt he was checking for damage: I hurt you.

“You’re lucky I took the blade,” Frithulf said, staring at him. “Isolfr? What’s wrong?”

Isolfr held out his hands to Viradechtis, and she came to him willingly, tail wagging, but her ears down. “Sister, no,” he said softly, trying to give it in her language as she had struggled to give her question in his. “I do not fault you.”

Her concern had outstripped her small store of words, but he could feel her love for him with astonishing depth and clarity. He had known that she would die for him, as he would die for her, but he had not realized that she would as willingly die for his happiness as for his life, that her loyalty was so much larger and simpler than anything men’s minds could comprehend. She understood that he had been hurt, but she did not understand how, and he could feel behind her that the wolfthreat did not understand either.

“Isolfr?” Frithulf said, and he shook himself awake to the fact that his friend was becoming as anxious as his sister.

“It’s all right, Frithulf. I need … I think Viradechtis and I need to walk.”

“And you don’t want company.”

“No.” The politics of wolves: say what you mean.

“Don’t go far,” Frithulf said, leaning to pick up the dropped axe haft. “Or we’ll have to send Kothran and Tindr to sledge you home.”

Isolfr grinned at the image and got slowly to his feet. “Come, sister,” he said, and Viradechtis followed him.

He had not gone deep into the pack-sense since the rut-madness had died away, but he took a deep breath, clearing head and lungs, and let himself open to it, let himself feel what he had been closing out. Pine-boughs-in-sunlight strongly, and then, with a strange formal feeling, the wolves who had topped Viradechtis: Mar, Glaedir, Ingjaldr, Guthleifr, Nagli, Egill. An honor guard, he thought, dimly understanding that they considered themselves … bound? Was bound the right word? Bound to Viradechtis while she carried their pups. And if they were bound to her, then they were bound to him. To the wolves it was that simple, and he did not look beyond them to their brothers. Not yet. And past Viradechtis’ males, the wolfthreat, its great warm awareness enfolding him, and he knew that if he had left the wolfheall he would for the rest of his life have been like a blind man yearning for the sight of sunlight.

With the pack-sense, it was easier to show her, because the wolves were certainly aware of their brothers’

couplings with women, with other men, and Vigdis, from the distance of a long patrol circling back home, unexpectedly contributed her memories of Hrolleif and Grimolfr, showing her daughter—perhaps for the last time as mother to daughter rather than konigenwolf to konigenwolf—the difference for a man between a mating with one other and a mating with many.

Viradechtis listened; he could feel her thinking, feel her sharp mind striving to comprehend something that was entirely outside its ken. Then he blushed scarlet when she put forward her memories of his couplings with Hjordis and, previously, the thrall-women. Those encounters had made her uncomfortable, making her groom her sex irritably and sometimes driving her to mount her brother Kothran, although it was not the same and did not appease the itch Isolfr’s couplings awoke. But it did not … her comparison was the bite of a horsefly, and he snorted embarrassed laughter, hoping that Hrolleif had his mind on something other than the pack-sense at the moment.

It took him several tries, but he found a way to show her that men did not rut as wolves did. She gave him a picture, unintentionally brutal: himself, on his knees, begging with every fiber of his body for Skjaldwulf’s touch. And he said, as firmly as he could, wolfbrother.

Her version of Gunnarr, stringy and bad-smelling and conspicuously without a wolf by his side. And he agreed with her, biting his cheek savagely to keep from laughing, that Gunnarr did not rut. She showed him Grimolfr, whose wolfname Isolfr caught for the first time: the smell of cold black iron. And Isolfr pointed her back to Vigdis’ sharing of Hrolleif and Grimolfr. Grimolfr felt rut. Wolfbrother, he thought again, not in words, but in the feel of it, what it felt to be a man bonded to a wolf.

He had stopped walking as soon as he was far enough from the wolfheall to be safe from interruptions, stopped and sat down, a little more heavily than he liked, on a fallen tree. The sun was falling down the sky, the wind picking up, but he wanted this clear between them before they headed back. So he sat and shivered and waited while Viradechtis thought.

She laid her head across his knees and gave him another image of himself, this time a younger version, saying, she is worth it. He was astonished at her memory, that she could give him the sounds accurately, even though she did not entirely understand what they meant. But the feeling that went with them … there was her question, there was the root of her question, and there was another flash of memory, there and gone, of him turning away from her, refusing her touch, and he understood that he had hurt her as surely as he had been hurt.

But her question was not so easy to answer. He remembered his younger self, discovering that “honor” was not a simple daylight concept, and now he thought he was discovering that “worth” was not, either.

He doubted he would ever say again, so glibly, that she was worth it. But she was his, and he was hers, and whatever price he’d paid was paid already. There was no use in demanding it back—and was it any greater cost than Frithulf’s scars, when it came right down to it?

“I belong to you,” he said to Viradechtis, knowing that that was truth, that “worth”—whatever it was—was not even the point between them. “I love you.”

Neither of those made any more sense to her than “worth” did. He went deeper into the pack-sense again, trying to find something that she could feel, something that would ease her. And he found it, found it in her own uncomplicated loyalty that did not care what he did or how he treated her. He gave that back to her, as clearly as he could, with as little taint of the overcomplications of his own relentless mind as he could manage.

She pushed her head harder into his stomach. Wolves did not apologize, for it was not their nature, but she was not quite a wolf any longer, just as he was not quite a man. She was sorry he had been hurt, sorry—though the concepts were as elusive as fishes to her—that her nature and his did not match. And she loved him, with such joy, such fierceness, that she ended up pushing him backwards off the log, to land with a thump in the dead leaves, the wind half knocked out of him and unable to catch his breath for some minutes because he was laughing so hard.

EIGHT

It wasn’t so hard to find tithe-boys after Othinnsaesc. The wolfless men were scared, and the boys, imaginations fired with tales of the campaign in the Iskryne, were eager. Viradechtis was fretful and snappish as her girth increased. Ingrun and Kolgrimna came into heat in quick succession, as if Viradechtis had set them off, which Hrolleif said wasn’t unlikely.

This time, Viradechtis got the records-room. The litter was seven pups, all dogs. Isolfr stayed with her as much as he could, but there always seemed to be something demanding his attention—messages from Franangford, which Hrolleif insisted he listen to, and understand.

It was nearly spring and Viradechtis was outside, teaching her pups the skills they would need as trellhunters, when Hrolleif pulled Isolfr into the records-room and explained with the simple bluntness of wolves, “Your little girl’s next heat will be her last one as second at Nithogsfjoll. She’s ready for her own pack, Isolfr, and you must be ready to be her wolfsprechend. Franangford will need strong pack leaders to take the place of the fallen.”

Isolfr nodded, biting his lower lip. His beard was coming in heavier, a patchy, itching thatch that was long enough to plait, now, and the wolfheall’s women had been letting the seams out of his shirts across the shoulders. And Viradechtis was unapologetically ready to be matriarch of her own pack. “We’ll have to alert the other wolfheallan,” he said, uncomfortably. “Before the mating. But that’s a year or two hence—”

Hrolleif shrugged. “It could be six months,” he said. “She won’t fall neatly into her mother’s pattern anymore, Isolfr. Ingrun and Kolgrimna are evidence enough of that.” Isolfr must have blanched visibly, because Hrolleif laughed, and reached out to clap Isolfr’s shoulder. “Don’t worry. Next time, she’ll be choosing her wolfjarl as well as the father of her cubs. It will be different.”

“Different,” Isolfr said, letting his lips twist wryly. “Aye. The strongest and best of eleven wolfheallan will be there, and every arrogant hopeful therein.” He frowned, thinking of the hard way Eyjolfr watched him now, remembering the biting wit of tall Vethulf and Viradechtis’ interest in his odd-eyed brother, and then he almost laughed when he realized that the most tolerable outcome would be Skjaldwulf and Mar. At least they were gentle.

And he knew and trusted them.

He didn’t think Mar was the strongest wolf in the Wolfmaegth, though.

Hrolleif seemed content to let him contemplate his future for the time being, but their companionable silence was interrupted by a scratching at the records-room door. “Come,” Hrolleif called.

It was Ulfbjorn, his broad shoulders brushing the door-posts. He glanced from Isolfr to Hrolleif, as if not quite sure where to begin. “There’s a man and his brother from Franangford, with news of the war.”

“Who?” Hrolleif dusted his hands on his trews, already moving toward the door.

There was a pause before Ulfbjorn replied, and Hrolleif stopped, his eyebrows rising.

“Kari. And his brother Hrafn,” Ulfbjorn said.

“Well,” said Hrolleif. He shared a glance with Isolfr, and Isolfr remembered where he had heard those names before—a bonded pair, and neither name the name of a wolfcarl.

The Wolfmaegth subsisted on gossip. Isolfr’s own reputation was his despair, even subsumed as it mostly was in his sister’s, and he knew werthreat and wolfthreat alike were waiting with undisguised interest to see what sort of pack Viradechtis would create. But Isolfr and Viradechtis were not the only ones attracting interest this winter; Kari and Hrafn had been the source of some very choice gossip indeed. “The wildlings,” Isolfr said. Hrolleif nodded, preceding him through the door.

As the story went, Kari had been the sole survivor of the troll attack on Jorhus. He had fled to the woods, and when the burning of Jorhus spread—for trolls were careless with fire—he rescued and bonded with a wild half-grown trellwolf, whom he had named Hrafn. The two had lived on t

heir own for the better part of a year before presenting themselves at Franangford, where they had been taken in. Kari, however, had flatly refused to take a wolfcarl’s name.

Franangford had lost both konigenwolf and wolfsprechend that winter to a troll sortie—unexpectedly encountered less than five miles from the wolfheall—and had been all but annexed by Arakensberg. Frithulf had had things to say about that, and a wicked gift for acting out the bitter rivalry between Grimolfr and Ulfsvith Iron-Tongue; he’d even made Hrolleif laugh once. So Grimolfr’s choice of this particular wolfcarl as messenger meant something, and Isolfr wondered just where Kari stood in the uneasy tug-o-war between Arakensberg and Nithogsfjoll.

Then he blinked and had to smile at himself, playing politics as if he’d been born to the Wolfmaegth.

Whatever his father might have done since Isolfr left the manor, Gunnarr had prepared his children well.

Kari was neither tall nor stern, and if anything he was a summer or two younger than Isolfr, lightly mustached and not yet showing more than a trace of beard. But he had a wiry, wild sort of dignity, even with his mouse-colored hair worked loose from its braids to straggle into his eyes, sweat plastering stray strands to his cheeks and forehead. The rangy wolf crouched at his side was black, darker even than Mar, marked with a mask like a stippling of hoarfrost, watching the proceedings with pale yellow eyes.

“Hrolleif,” the boy said, and then his eyes flicked curiously to Isolfr.

Hrolleif made no introductions, so Isolfr said his name, which seemed to satisfy the messenger. Around the wolfheall, others—wolves and wolfcarls—were watching, but Kari pitched his voice low, so that it would not carry. “Grimolfr bids you greeting, wolfsprechend—and Isolfr, as well.”

It was obviously Kari’s own addendum, but Isolfr found he appreciated the gesture. “The news is ill,” he said, not quite asking, with a glance to Hrolleif for permission. Hrolleif nodded and shifted his weight back, folding his arms.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

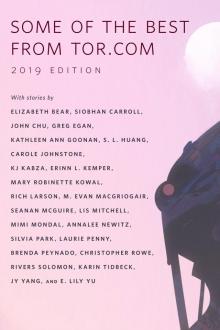

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

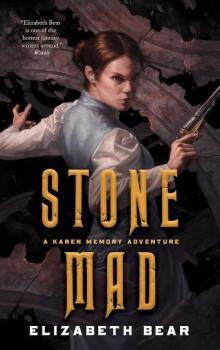

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

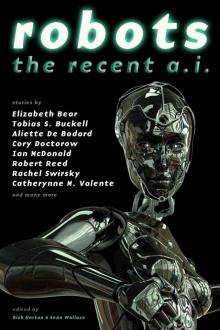

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

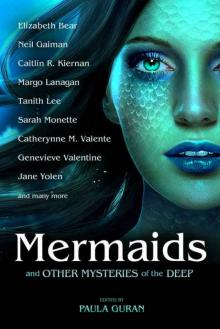

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

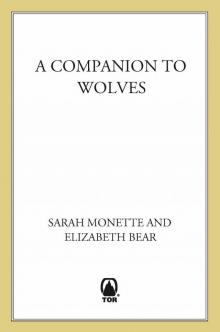

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

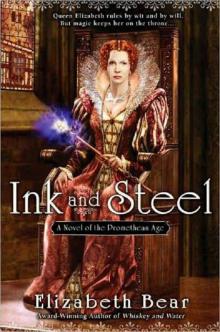

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3