- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Ink and Steel pa-3 Page 3

Ink and Steel pa-3 Read online

Page 3

“I cannot write as Kit did.”

“You will,” Lord Hunsdon promised. “You’ve a gift in you, man in your Comedy of Errors, and your Henry VI. You’ll write as Kit did, and better.”

“And wind up like Kit as well, no doubt, with a knife in the eye.”

Henry was half Marley’s, Will thought, but didn’t correct the lord Chamberlain. Juice dripped over Will’s hand, but Will did not raise the fruit to his mouth.

“There is that risk,” Oxford allowed. A light wind ruffled his fine hair as the day brightened and warmed. A dove greeted the sunlight with cooing, and starlings fluttered on the grass.

“We have enemies.” Lopez’s accent was less than Will had imagined. He tucked his hands inside the drooping sleeves of his black robe, posture imperious, expression cold. “Mistake it not. Our society was quite infested by traitors, loyal to Spanish Philip or to themselves. We’ve picked them from the ranks, but Kit is not the first of our number to fall to their machinations.”

Perhaps it was the chill in Lopez’s manner, the dismissal. But Will rallied against it, when he might have bent under greater sympathy.

“It’s whispered in the kitchens, Doctor, that your swarthy hand was behind the poisoning of Walsingham.”

“Aye,” said Lopez. “And who spreads the whispers, playmender?”

“Will,” Burbage whispered.

“Won't.”

Burbage took a step back. Will felt six men lean toward him. “Won’t wind up like Kit,” he amended. “I mean to die in mine own bed, warm and comforted. There’s no way out of this once I’ve accepted, is there?”

“There’s no way out of it now, Walsingham said kindly. I won’t lie to you: we stand only for Elizabeth, and nothing else. No Church or love of God or man may come between us and the love of our Queen. Our enemies stand against us with weapons fouler than a knife in the eye.”

“What? Cannon? Sedition? Gunpowder?”

“Plague,” Hunsdon answered. “Poison. Sorcery. Politics. The wiles of men who should be removed from secular things; the Catholic and Puritan factions who plot against the Queen are their dupes.”

“Puritans and Sorcery? Odd bedmates indeed.”

“I’ve seen odder, Walsingham replied, a shadow darkening his brow. “They are puppeted by shadowy hands. Including, it seems, hands I have trusted in the past.” Walsingham’s gaze dropped to the lemon in his hand. He raised it to his mouth, lips pursing tight when he tasted the juice.

Will contemplated his own half fruit. “And all I must do is write plays?”

“All you must do,” Burbage answered when no one else would, “—is write plays. And love Gloriana. Welcome to the Prometheus Club, Master Shakespeare. Long live the Queen.”

When he bit down, Will tasted shocking sour and bitterness, and the salt of Walsingham’s hand.

Act I, scene ii

Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscribed

In one self place. But where we are is hell,

And where hell is there must we ever be.

CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE, Faustus

Kit awoke in darkness, confirming his suspicions. Secretly relieved not to find himself in a lake of fire, he would never have admitted it to a theologian. It was dark, aye, and the right side of his face felt

“Tom. Tom, how could you have betrayed me? Oh. Oh,” he said and tried to sit. Nausea and vertigo swept him supine again. He groaned; cool hands pressed a cloth across his eyes. Long hands and calloused with work, but tapered: a woman’s, redolent of rare herbs and roses.

“In faith, Rosemary,” he said, so he would not hiss in pain. “I hope I’m not dead. I thought death was meant to be an end to worldly cares, and here I find rather less release than might be hoped from a knife in the eye. Tell me then, be I dead, or in Cheapside?”

“Neither dead nor in Cheapside, sir knight,” an amused voice answered. “And you’ll find the legend of your wit precedes you. Drink, if you’ll risk it.” The cool fingers touched his lips, and water dripped into his mouth.

“Water?”

“No, some tisane, sweet with honey and tart with lemons. Rosehips and catmint. Better?”

“No knight, he answered. But a playmaker. Yes, better by far than the taste of my oversleeping. Was I fevered?” He put a hand up to cover hers, but his trembled and hers was strong.

“Bards are honored as much as knights here,” she answered. “And you re a Queen’s Man, which makes you more a servant of the crown than many entitled to a Sir. You are lucky to be alive.”

That did open his eyes—his eye, as the right one seemed swollen shut. He remembered a knife in the hand of his master’s man.

Poultice or no, he sat, pulling the wet cloth aside. His ring was missing, the gold-and-iron ring Edward had given him.

“Where did you hear such deviltry, woman?”

She was tall. Hair black and coarse as wire, gray at the temples, strong and fine of feature with an aristocratic nose. If she’d not had her hair twisted into a simple straight braid and been dressed in gray-green linsey-woolsey, he might have said she was like enough his Queen to be Elizabeth’s own cousin.

“From Gloriana,” she replied, straightening her spine like a Queen herself. “And before you ask why you live, Kit Marley, Queen’s Man, call it a favor from one Queen to another.”

She plucked the cloth from his hand, and he winced to realize that it was daubed with clotted blood and a few red streaks that were fresher. And that he was shirtless as well, and the skin of his chest was damp. His head pounded at the assault of the light.

Kit decided he’d as well err on the side of caution. “Beg pardon, my lady.”

“Head wounds are bloody, she said, turning away. Art pardoned. What?”

“Your name, that I may repay this service?”

She stopped with a fresh soaked cloth in her hand. And smiled. “May a man serve two Queens?”

He opened his mouth to answer, but she waved him still. “You’d know me as Fata Morgana.” She held out her cloth. He took it, and she turned away again. “But you may call me Morgan. Welcome to the Bless’d Isle, Christofer Marley, like many a bard stolen before you.”

He blinked, and his head felt so much better for closed eyes that he kept them that way. “You speak a fair modern tongue for a wench a thousand years dead.”

“One strives to be current.” Her hands on his again, and a smell of wine as she pressed a goblet on him. “Drink.”

“And have you drug me?”

“Would have done it with the tisane, Sir Kit, had I mind.”

“Again you sir me, Rosemary. Or is your name Rue?” he said, but he drank. I twas black currant wine, or perhaps elderberry: sweeter than the grape, and more potent. He tasted herbs in it, and sandalwood and myrrh. “Yppocras.”

“To strengthen your blood. You were hurt. Stabbed and left for dead. And buried without a wake.”

“How badly?” He opened his left eye. “May I see a glass?”

The chamber was homely, despite rich furnishings that did not match the plainness of her gown or hairdressing. He judged it hers, though, by the dress laid across the clothespress and the comfortable way she moved about, barefoot over golden flagstones and heavy patterned carpets in place of rushes an enormous luxury. A cool breeze blew in, the shutters standing open to the night. It did not feel like May.

“We’ve no steel,” she answered. “But here.” From her belt she drew a silver blade, a dagger twice the length of his hand, polished like a looking glass. She held it up; he tilted his head to get the lamplight at a likely angle.

The right side of his face was seamed with dried blood, for all the lady’s bathing, and as ugly a cut as he’d seen laid bone plain from brow to a cheekbone almost lost in a welter of puffed flesh and purpling bruises.

“S’blood, I can see why they left me for dead.” He frowned when she flinched at the oath. “Pardon, my lady.” She might be mad, but she had been kind.

“It’s not the cu

rsing. It’s the oath.”

“Your pardon in any matter,” he answered as prettily as he could. “For if I have your pardon, it cannot matter what fault enjoined it, and if I have not your pardon, then I shall have to facet my flaws to the light until you find one that sparkles prettily enough for forgiving.”

She snorted. “Not a knight indeed. Ferret-quick, she lifted the poignard in her hand. Before he could flinch, she slapped him hard with the flat on each shoulder, numbing his left arm from shoulder to wrist.

“There. That’s done it. I dub you Sir Christofer. I’d make you a Knight of the Table Round, but if my brother ever wakes I’d hear of it. So you’ll have to settle for Cornwall and Orkney and Gore. Twill serve?” She studied his face intently, birdlike.

“Twill serve.” He made as if to stand, sliding his legs over the edge of her bed. She’d left his breeches where they belonged, at least, but her frank appraisal as she drew the curtain aside pulled a blush across his cheeks and made his swollen face ache. With a smile like that, were I less hurt, I’d try my luck with her. No blushing maiden, this. “My lady?”

“It will scar, she replied,” as if he’d asked the whole question. “And badly. But a Queen’s Man’s the better for a few of those, earned with honor.”

He flinched again. ‘So much for any secrecy I might have been left. But I can’t fault her herbwifery. And at least she hasn’t mentioned blasphemy. Or sedition. Or sodomy.’ He wondered if she might be one of Queen Elizabeth’s rumored bastards. The longer he looked, the stronger the likeness grew.

“Will I keep the eye?”

“No,” she said flatly. “Not a chance. You could let it scar closed, but there’s less chance it will take a taint and kill you if you wash with clean boiled water and let it drain.”

“Oh.” He sat back against the bed, his bare feet flat on her carpeted floor.

“Sir Kit One-eye.”

She spiked him a frown, and he grinned in return, although it stung.

“Oh, Tom.” After everything It was an ache in his chest as if cold fingers closed over his heart, stopped his breath. He laughed past it. “Could have been Kit-in-his-Coffin, though.”

“By the breadth of a finger. Finish your wine. When you re dressed, if you can walk, you’ll see the Queen.”

The Queen, he thought, and breathed out in relief as he raised the cup.

Morgan showed him a white-painted wooden tub behind a screen, with flannels and cakes of scented soap attending steaming water. The screen was a delicate lacework of pale stone. “Soapstone,” she said when she saw him running curious fingers over it. “From the Orient. You have clever hands, Sir Christofer.” She caught one and studied it, then lifted direct gray eyes.

“How many have you killed with them?”

Despite the silver in her hair, her face was no older than his; her thumb traced circles on his palm. Every sentence from her lips was a fresh assault on his practiced masks, and he swayed between stepping forward and stepping back.

“More than I wanted.” His plain tone was its own surprise. “Fewer than I should. I must get a message to Walsingham.”

She touched his face lightly before letting her hand trail across his collarbone and the bruise her dagger had left.

“Your murderers know not that the corpse they planted was but glamourie, and gone by sunrise of the day following and in a year, who could find the grave? They buried you in a winding sheet, without a marking stone. They said you died blaspheming. Not the first knight to fall so.”

“I did? I remember Ingrim, the great oaf, slinging me about by a hand in my hair, and with a dagger in his other. And Poley and Skeres held me down.” There were other memories in that, old ones Kit wanted not, though they came up anyway on a spasm like bating wings. Then pain, and great blackness.

“Blaspheming? No truth in the accusation, but vilest contumely! I do attract it: my wit and good looks.” He touched his ruined face lightly, came away with gummy blood on his fingertips.

“Can you get a message to Walsingham?”

“Twas Walsingham’s men did this to you.”

Kit shook his head and regretted it.

“Sir Francis, not that book-chewing rat of a Thomas, who had the gall to call himself a friend to me.”

He wondered if she could hear the grief in his tone. From the way her head cocked, birdlike, she did.

“I must advise Sir Francis that I live.”

Sensation was returning to the right side of his face. It would have hurt less if it had been carved clean away.

“He’s dead himself, Kit. Hast the blow to thy head addled thee? Gone from thy Queen’s service these five years, and gone to his reward these three. However Queen’s spymasters are rewarded. Unjustly, if earth models heaven.”

She stepped away, leaving his flesh burning where her hand had pressed it.

So she doesn’t know all my secrets. Lacrima Christi. He let his breath trickle out, relieved and enflamed. The Privy Council, the Queen must have interceded, to bring me here and under care. At least I’ve the proof I give good service.

Morgan’s black braid flagged against her shoulder like a banner.

“You’ll want to scrub that wound with soap once you’re in the water.”

“Is that wise?”

Her hem whispered over stone as she vanished around the screen. “It’s all that could save you. If the wound goes bad so close to the brain, well, it’s not as if we can amputate. Soap will cleanse the wound. And hurt. Not so much as when I sew and poultice it. As I’ll have to if you want a neat, straight scar and not a mess of proud flesh.”

He winced at the thought, then unlaced his breeches and tested the water on his wrist.

“Do you care for a man in an eye patch, my lady?” No answer, but he thought he heard a chuckle. The water came to his chin and was hot enough to make his heart pound once he settled in. A deep ache spread across his back, thighs, and shoulders as tight muscles considered relaxation. He leaned against the carved headboard and stretched his toes to meet the foot.

“Scrub,” she reminded. He sighed and picked up the soap.

When he was half dressed again, she washed the cut with liquor until white, clean pain streamed tears down his face. But it throbbed less after, and his head felt cooler. The stitching was worse, for all she fed him brandy before. The needle scraped bone as she tugged his scalp together and sewed it tight; he whined like a kicked pup before she finished.

“Brave Sir Kit,” she whispered when she’d tied the final knot.

He leaned spent against a bedpost.

“Braver than lance was over his wounds, when I dressed them. He spat and swatted like a cat.” She gave him more brandy and bound a poultice across the right side of his face. When he set the cup aside she leaned down and licked the last sweet drop from the corner of his mouth. He startled, gasping, but regretted it when she leaned back, eyes narrowed at the corners with her smile.

“My lady, I am not at my best.” And then he worried at the knot in his gut, the fascination with which he followed her.

‘This is not like me. Anything to think of, but Tom.’

“Welcome to Hy Brásil, poet.” She balled up the cream silk hanging on the pale oaken bedpost and threw it against his chest. “Put your shirt and doublet on. It pleases the Queen to greet you.”

He dressed in haste: the shirt was finer stuff than he’d worn, and the dark velvet doublet stitched with black pearls and pale threads of gold, sleeves slashed with silk the color of blued steel.

“What royal palace is this?” he asked as she helped him button the fourteen pearls at each wrist.

“The Queen s. They re all the Queen’s.”

“Westminster or Hampton Court? Whitehall? Placentia?” He scrubbed golden flagstones with a toe and noticed that someone had polished his riding boots until they shone like his shirt. The pressure of bandages across his face calmed the pain; he hazarded a smile.

“Call it Underhill.” She tugged

his collar straight. “Or Oversea, and you won’t be far wrong. Names aren’t much matter, unless they re the right name. There.” She stepped back to admire her work. “Fair.”

“Art my mirror, then?”

“The only mirror you’ll get but a blade.” She’d changed her dress while he was bathing and wore gray moir : no less plain than the green dress, but of finer stuff and stitched with a tight small hand. Slippers of white fur peeked under the hem, and he stole a second glance to be sure. Ermine. He was glad he hadn’t taken advantage of what the mad-woman offered, and resolved not to absentmindedly thee her again.

“Her Majesty does me honor.”

Morgan offered him her arm. He held the door open as she gathered her skirts.

“She has an eye for a well-turned calf.”

“I’ve an eye as well,” Kit admitted. “Only one anymore, alas. But it serves to notice a fair turn of ankle still.”

His voice faltered as they came through the doorway. His knees and his bowels went to water, as they hadn’t when Morgan showed him the gaping wound across his face. As they hadn’t when she kissed his mouth.

The door opened on a narrow railed walkway over a gallery that yearned heavenward like the vault of a church. The whole structure was translucent golden stone, carved in arches airier than any gothic-work, the struts blending overhead like twining branches. Between those branches sparkled the largest panes of glass he’d seen. Beyond the glass roof, through it, shone a full moon attended by her company of stars. People moved in eddies on the stone-tiled floor several lofty stories below; they passed through a guarded, carven double door two stories from threshold to lintel. Even from this vantage Kit could see not all were human. Their wings and tails and horns were not the artifice of a masque. He licked his lips and tasted herbs and brandy, and a kiss.

Fairy wine, he said, half-breathless with awe and loss and betrayal. I drank fairy wine. I cannot leave. Morgan le Fey stepped closer on his blind side, resting her strong hand in the curve of his elbow. I warned you about the tisane. And as long as you’re tricked already, we may as well see this ended so we can get dinner. Come along, poet. Your new Queen waits.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

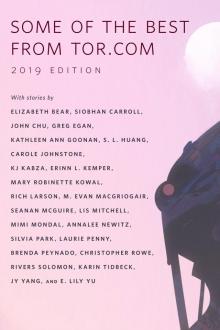

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

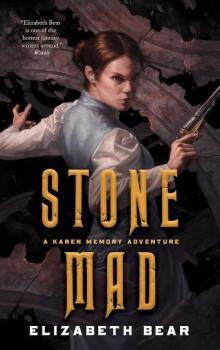

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

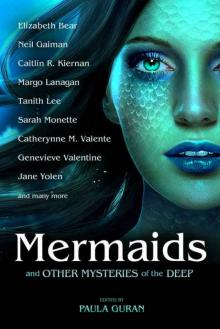

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

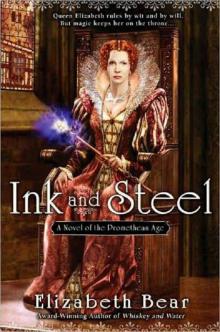

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3