- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Hammered Page 3

Hammered Read online

Page 3

She shook her head. “That was like, ancient history.”

A complicated expression crossed his half-concealed face. “So it was,” he agreed. “You should look it up; it’s very interesting.”

She might have felt insulted, except there was something in his tone that said that he really did think that interesting was a good enough reason to look something up. He kind of reminded her of her fifth-grade teacher, Mrs. Kology, who was her favorite teacher so far.

He kept talking, and something about his plain words and animated tone made everything seem very simple. I bet he’s a teacher in real life.

“It’s got a lot to do with gamesmanship,” he said. He hunkered down and ran his fingers through the iron-red dust underfoot, raking four parallel gouges. “Canada’s been in a lot of peacekeeping efforts in the last fifty years, which it couldn’t have done without corporate money. Some of the wars were really unpopular at home, especially after the universal draft instituted by the Military Powers Act, and there were some real problems with terrorism. Also, wars give rise to new technology. And with the United States tangled up in its internal affairs, there’s been nobody else with the—the sheer stubborn—to oppose China’s empire building.”

“I wouldn’t want to live in China,” Leah said definitively. She twisted one foot in the dust, watching it rise in soft puffs.

Tuva’s head bobbed down and he grinned wide. It was the kind of smile that rearranged his entire face, his eyes sparkling like faceted stones, and it drew a twin from Leah. “But politics … It’s very interesting, when you think about it.”

Leah shrugged, feeling young and uninformed. I’ll be fourteen in May. “There’s a lot I don’t know.”

“That just means you get the fun of learning it. Now then, where’s your half of the treasure map?”

Allen-Shipman Research Facility

St. George Street

Toronto, Ontario

Sunday 3 September, 2062

Morning

Elspeth pulled a shiny, never-used key out of her lab-coat pocket and fitted it into the handle of her door, simultaneously applying her thumb to the lock plate. The handle turned with a well-oiled click and she stepped into her office, savoring a sensation that had once been familiar—although she’d never had an office like this.

She couldn’t resist running her fingers over the realwood grain of the door and comparing it to battered yellow laminate with a window reinforced with chicken wire—or to plain barred metal, for that matter. “Lights,” she said, and the lights came on as if by magic. She paused for a moment just inside the door. “Lights off,” she said softly, feeling childish, and then “Lights,” once again.

Such a basic thing, illumination that did what you wanted when you wanted it to.

She set a white canvas bag embossed with a corporate logo down against the wall and wandered to the center of her office, leaving the door open. The scent of brewing coffee informed her that she wasn’t the first one in the building. Evergreen carpeting felt luxurious under feet clad in new oxblood loafers—Valens had given her a corporate card and instructions to outfit herself the previous evening—and pale spruce drapes outlined the long window behind her new desk.

Shelves lined the walls. She recognized the books that filled them: texts and journals on psychology, neurology, artificial intelligence. Beside them, biographies of some of the great minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Old, worn, many of them battered. Here also, holographic data storage crystals in racks, dozens of them. Hers, confiscated thirteen years before. State of the art, then.

Obsolete technology, now.

The dark wood of the desk gleamed with recent waxing under a clear interface plate, stainless-steel-and-gold desk accessories reflected in the shine. Elspeth took a deep breath, imagining that she almost caught the fragrance of traffic and a late summer, early autumn morning over the scrubbed tang of conditioned air. She opened her eyes, crossed the forest-cool confines of her office, and ran a finger along the neat white labels with their red underlines, hand-lettered and stuck on the flat-top surface of the crystal racks.

Handwriting inked in an erratic combination of green, red, and blue was not her own. It belonged to her former research partner. “Jack,” she murmured. Her eye ran down the little sticky tags, making out numerals, dates, and serial letters faded by the years. Farther down the rack, the labels changed and simplified. Dates and names, covering years of work. They had made daily backups, but saved only the monthlies due to space issues. They’d made daily headlines, too, for a while.

July 30, 2048: Truth, Tesla, Fuller, Woolf, Feynman.

November 30, 2048: Truth, Tesla, Fuller,

Woolf, Feynman.

May 30, 2049: Truth, Tesla, Fuller, Woolf, Feynman.

An empty socket in the rack for June 30 stood out, obvious as a missing kernel on a cob of corn. The last slot, the one labeled Feynman, was empty.

Elspeth licked her lips and glanced around her office. She didn’t see the cameras concealed among sylvan trappings, but she knew they must be there, recording every move. Nevertheless, she could not resist reaching out and running her finger across that last label—June 30, 2049: Feynman—and allowing herself a little, secret smile.

“Godspeed, Richard,” she whispered, and, turning away, walked to her desk, seated herself, and tapped her terminal on.

Twenty-five years earlier:

Approximately 1300 hours

Wednesday 15 July, 2037

Near Pretoria, South Africa

Fire is a bad way to die.

Even as I jerk back against my restraints, consciousness returning with the caress of flames on my face, I know I am dreaming. It’s not always the same dream, but I always know I am dreaming. And in the dream, I always know I am going to die.

I suck in air to scream, choke on acrid smoke and heat. The sweet thick taste of blood clots my mouth; something sharp twists inside of me with every breath. Coughing hurts more than anything survivable should have a right to. The panel clamors for attention, but I can’t feel my left hand or move it to slap the cutoff. Jammed crash webbing binds me tightly into my chair.

I breathe shallowly against the smoke, against the pain in my chest, retching as I fumble for my knife with blood-slick fingers. The hilt of the thing skitters away from my hand. As I scrabble after it, seething agony like a runnel of lava bathes my left arm. I think I liked it better when I couldn’t feel.

The world goes dim around the edges, and the flames gutter and kiss me again.

The pain reminds me of a son-of-a-bitch I used to know, a piece of street trash named Chrétien. I never thought I could like a kiss less than I did his. I guess I know better now.

I try to turn my head to get a glimpse of what’s going on with my left arm, and that’s when I realize that I can’t see out of my left eye and I’m dying. Oh God, I’m going to burn up right here in the hot, tight coffin of my cockpit.

If I die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take … Hah. Right. The hell you say. Pain is God’s way of telling you it’s not time to quit kicking yet.

Whimpering, I stretch away from the flames, reaching out toward the impossibly distant hilt of my knife. I’m listening for movement or voices from the back of my A.P.C. Nothing. I hope to hell they’re all dead back there, or far enough gone that they won’t wake up to burn.

Something tears in my left arm as I lean against the pain, clinging to it as my vision darkens again and I hear myself sob, coughing, terrified.

Please, Jesus, I don’t want to burn alive. Well, we don’t always get what we want, Jenny Casey.

And then I hear voices, and the complaint of warped metal, and a rush of light and air that makes the flames gutter and then flare. They reach for me again, and I draw a single excruciating breath and scream with all my little might. A voice from outside, Québecois accent like the voice of an angel. “Mon Dieu! The driver is alive!”

And then scrabbling, hands tugging at my

restraints, my would-be savior groaning as the flames kiss him as well. I catch a glimpse of fair skin, captain’s insignia, Canadian Army special forces desert uniform, the burns and blisters on his hands. Another voice from outside pleads with the captain to get out and leave me.

He squeezes my right shoulder, and for a second his gaze meets mine. Blue eyes burn into my memory, the eyes of an angel in a stained-glass window. “I won’t let you burn to death, Corporal.” And then he slides back across the ragged metal and out of my little patch of Hell.

The voices come from outside, from Heaven. That’s part of Hell: knowing that you can look up at any time and see salvation. “His goddamned arm is pinned. I can reach him, but I can’t get him out.” That explains why I can’t move it. I am suddenly, curiously calm. They’re arguing with him, and he cuts them off. “I wouldn’t leave a dog to die that way. Clive, you got slugs in that thing? Good, give it here.”

I hear him before I see him, thud of his boots, scrape of the shotgun as he pushes it ahead. What the hell. At least this will be quick.

I turn my head to look at him. He has a boot knife in his hand as well as the twelve gauge, and I just don’t understand why he’s cutting the straps of my crash harness. He cuts me, too, and I jerk against the straps, against my left arm. “Dammit, Corporal, just sit still, will you?” I force myself to hold quiet, remembering my sidearm and worrying that the heat will make the cartridges cook off before I remember how soon I’m going to be dead.

His voice hauls me back when I start to drift. “Corporal. What’s your name, eh?”

Spider, I start to say, but I want to die with my right name on someone’s lips, not my rank, not my handle. “Casey. Jenny Casey.”

I feel him hesitate, see his searching glance at my face. He hadn’t known I was a girl. I must look pretty bad. “Gabe Castaign,” he tells me.

Gabriel. Mon ange. It’s one of those funny, fixed-time, incongruous thoughts you get when you know you’re going to die. And then the knife moves, parting the last restraint, and he drops it to bring the gun up and brace it. I look at the barrel, fascinated, unable to look away. “Sorry about this, Casey.”

“S’aright,” I answer. “’Preciate it.”

And then the gun roars and I feel the jarring shudder of the impact, and there is only blackness, blessed blackness …

1930 hours, Monday 4 September, 2062

Hartford, Connecticut

Sigourney Street

Abandoned North End

… and the buzz of the door com hauling me out of cobwebby darkness and into the blinking light. My hand’s on my automatic, the safety thumbed off—“If I catch any of you using his finger, I will break it.” Master Corporal, I believe you would have—before I’m fully awake and the reality of the situation comes back to me.

My clothes are wet, my neck is killing me, and my damn glass has broken on the floor, littering it with pale blue shards and a wet stain that soaks into the cement. The book I was reading is still sliding from my lap, the arrogant, aristocratic silhouette of a long-dead movie director embossed on the spine. I catch it before it hits the floor, check the page number, and toss it into a crate with the others I haven’t gotten around to yet. They are all paperback, ancient, and crumbling. They—the universal them—don’t print much light reading anymore.

Holstering the sidearm, I creak upright and limp to the sink after grabbing my jacket off the chair I fell asleep in. I’ll be paying for that lapse of judgment for a while.

The buzzer again, the echo made harsh by the cementlined, metal-cluttered cavern I call home. I raise my eyes to my monitors. Activity on only one—the side door, a single figure in a familiar dark coat. Wet hair straggles into his eyes; he stares up at the optic and gives me the finger. Male, Caucasian, under six feet, slender but not skinny. The monitor is black and white, but I happen to know that he has brown hair and hazel eyes and a propensity for loud ties.

I lean over the sink and thumb on the com with my left hand. “Mitch.”

“Maker. You gonna let me in?”

“Got a warrant?”

“Hah. It’s raining. Buzz me in or I’ll go get one.”

He’s kidding. I think. “Got probable cause?”

“You don’t wanna know.” There is a certain grimness in his voice that cuts through the banter. I stump over to the door and open it. He drifts in with a smell of sea salt and Caribbean foliage—the alien breath of tropical storm Quigley, which left its fury over the Outer Banks two days before. Seems like we get farther into the alphabet every year.

Turning my back and trusting Mitch to lock up, I think, I have to fix the buzzer one of these days.

I put my jacket down on the counter and turn on the water, cold. Splash my face. Watching Mitch in the mirror, I stick my toothbrush into my mouth. Mitch slips into the shop and shuts the door firmly, checking to make sure it latches. Then he picks his way catlike between the hulk of an Opel Manta much older than I am and a 2030 fuel cell Cadillac that probably has another life left in it.

Mitch circumnavigates a bucket and saunters over to my little nest of old furniture and ancient books. He pauses once to stoop and offer a greeting to Boris, the dignified old tomcat that comes by to get out of the rain.

I grin at myself and salute the mirror with my toothbrush. Spit in the sink, rinse, and turn off the water as Mitch leaves Boris and ducks under a hanging engine block. “Damn, Maker. It’s like a blast furnace in here.”

Cops are a lot like cats, come to think of it. They can tell when you don’t want company. That’s when they drop by.

“Been cold enough in my life.” I tuck the hem of my T-shirt into the top of my worn black fatigues and tighten the belt. Mitch stares for a second overlong at my chest, and then his eyes flick up to meet mine. He grins and I grunt.

“Save the flattery, eh? I own a mirror.”

He crosses the last few feet between us. “I like tough girls.” Matter-of-fact tone. Good God.

“I’m not exactly a girl anymore.” I’m old enough to be his mother, and I wouldn’t have had to start real young, either. “And I look like I’ve been through the wars.”

His grin widens. “You have been through the wars, Maker.” He hops onto the edge of the old steel table, his jacket falling open to reveal the butt of his gun. Hip holster, not shoulder. He wants to be able to get at it fast, and he doesn’t care who knows he has it.

I turn my back on him and pick up my own jacket from the edge of the sink, shrugging into it before turning my attention to the buckles. Despite the weapon on my own leg, I have an itch between my shoulder blades. Some people get used to guns, with practice. I never did. Guess I’ve been on both ends of them too many times. “To what do I owe the pleasure?”

I glance back as his smile turns grim. “A bunch of dead people.”

“We get a lot of those around here.” I tighten the last buckle on my jacket, well-beloved leather creaking. The coat is on its third lining, and I stopped replacing the zippers long ago. I got it in … Rio? I think. The cities all blur together, after a while. It was my present to myself after surviving my second helicopter crash.

There hasn’t been a third one. Small mercies. I turn back and take three limping steps to fuss with the coffeepot. Damn knee hurts again, no doubt from the storm. What’s worse is when my arm hurts. Metal can’t ache, but you could sure fool me.

“These dead people might worry you some.”

“Why’s that?” I pull my gloves from my pocket and yank them on. Driving gloves. The metal hand slips on the wheel, without. It’s an excuse not to look him in the eye as I ever-so-carefully adjust black leather over rain-cold steel.

“Because you know something about the Hammer, Maker. From when you ‘weren’t’ in the army. Special forces, was it? Nobody else gets that stuff.”

In the silence that follows, the coffeepot burbles its last and I jump, fingers of my right hand twitching toward the piece strapped to my thigh before I stop them. Wisely

, Mitch does not laugh. Jenny Casey’s law of cops: there are three kinds—5 percent are good, 10 percent are bad, and the rest are just cops. The good ones want to help somebody. The bad ones want power. The rest want to ride around in a car with a light that lights up on the top.

I tolerate Mitch because he’s one of the 5 percent. Snotass attitude and all.

He gets up off the counter and reaches for the coffeepot, turning his back to me.

“What makes you think I was army?”

“Where’d you get the scars?” He hands me a cup of coffee before pouring one for himself.

I take it in my right hand, savoring the heat of the mug. “Playing with matches.”

He laughs again, and again it does not sound forced. Stares at my tits, laughs at my jokes, the boy knows the way to an old woman’s heart. “Did Razor ever find that dealer?”

I don’t wonder how he knows. “Any bodies turn up in the river?” The broad, blue Connecticut. Lake Ontario, it isn’t. But hell, it’s a decent-sized river—and every time they drag it, they find a couple of people they didn’t know were missing.

Mitch sets his cup aside and pins the floor between his lace-up boots with a glare. He’s wearing brown corduroy trousers, ten years out of style.

I wonder if I’m still drunk. The glass on the floor annoys me, and I turn away to get the broom and dustpan. Stooping over, I look up at Mitch. He’s stuffed his hands into his pockets, and he leans back against the table to watch while I sweep the concrete. I have to drop down to hands and knees to get the shards that scattered under the chair, and I wince and groan out loud when I do it. Something that feels like shattered pottery grinds in my knee and hip when I straighten.

Mitch chews his lip. “Getting old, Maker.”

“Still kick your boyish bottom from here to Boston, Detective.” I carry my loaded dustpan over to the trash.

“Where the hell does that name come from, anyway? Maker. Radio handle? You guys used those, didn’t you?”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

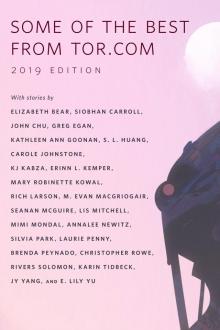

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

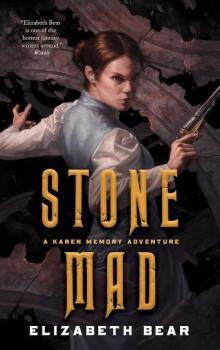

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3