- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Dust jl-1 Page 4

Dust jl-1 Read online

Page 4

"Oh," Perceval said. "I wondered, when I didn't see you." She sat down on the pallet, wrapping her arms around her knees, wincing when she moved. Somebody had made it up tight, and Rien did not think Roger would have done so.

Rien crouched beside her. There was enough cloth in the trousers to make a pair of skirts, and they puddled on the floor around her feet when she squatted. She laid her left hand on Perceval's arm, without looking at the prisoner, and was shocked to feel her skin so dry, crepey and hot.

"If you got back to Engine," Rien said, "do you think that they would stop the war?"

She hadn't understood her plan until she spoke it.

For a long time, Perceval did nothing. Then she turned, tendons stretching in the long line of her neck, and said, "It depends, don't you think? Tell me what's going on."

Quickly, softly, Rien told her. That Perceval's capture and mutilation had been the trigger of Lady Ariane's plan. That she had meant, no doubt, to overthrow her father and bring Rule to war with Engine, from the start.

That Engine had obliged.

Fever-bright, Perceval listened. And then she folded her bony forearms one over the other and rested them on her knees, the chains a long silver-blue sweep framing her on either side, her chin pillowed on her bony wrist. "It doesn't matter," she said, after chewing her lip a little. "I'm never getting home, am I?"

Not believing what she was doing, Rien reached into her pocket, down into the depths of the soft swinging dark cloth, and drew out the control. "But I don't know the way out of Rule," she said, when Perceval's eyes finally focused on it.

"Oh," Perceval said. "That's all right. I do."

When the chains slid from her wrists and ankles, Perceval thought the sting in her eyes would blind her. She shuddered, forehead on her arms, and almost wept.

And then she gathered her courage, tented her fingers on the pallet, and pushed to her feet. "We'll go to Father," she said, decisively. "Rien, may I have the key?"

Rien hesitated, but seemed to have made up her mind. She gave Perceval the box, and Perceval used it to tweak the draped chains into a sleeveless column dress, something to hold heat against her skin. She shed the blanket without a glance, and though she winced when she raised her arms to wriggle in and the touch of the fabric made her skin crawl, it was good to have something between her and the world. "Father," Rien said. "Lord Benedick." "Who else?" For a moment, Perceval considered crushing the controller, locking the dress into that shape unless and until the colony could be reprogrammed. But there was the risk that someone in Rule had another control for this colony, and it was far too useful a tool to abandon.

"Isn't that..." Rien, when Perceval turned back to her, stood with her face screwed up, seeking the right word. "... presumptuous?"

Perceval bit her lip. This was probably not the best of times for her to admit how distant her own acquaintanceship with Benedick was, but she would not lie. So she said only, "For his daughters to call in time of need?"

There was a pause. A lingering contemplation. And then Rien shook her head. "You meant it. That we are sisters."

"Yes," Perceval said. And when Rien just stood, staring and shaking her head, she grabbed the young woman's wrist and dragged her along.

Climbing was anything but easy. Perceval was fevered, and her blood—still shocked by the unblade and the amputation of her wings—was not fighting as it should. She must haul herself ten or fifteen spiral steps and then pause, resting one hand on the wall, reeling. But after the third time, Rien seemed both to understand and come back to herself, and begin steadying Perceval up the stairs.

It went faster then.

When they came to the courtyard level, everything was still the indigo of evening. Rien stopped Perceval with a hand on her shoulder and stepped forward first, just to the edge of the door. She glanced cautiously each way—about as nonchalant as a stalking cat, but Perceval wasn't about to tell her so—and then stepped forward.

If there was a night watch—as there would be in any sensible holde: who would wish to trust his breath only to automatic alarms?—it was elsewhere.

Or so she hoped, until they crossed between a massive tree that must have been planted when the world was made, turned down a side corridor, and found themselves face-to-face with a young woman with a stunner at her hip and a lightstick in her hand.

"Rien—?"

The girl was a Mean, pink of skin and slow to move. In pity, Perceval only broke her wrist and struck her once hard over the sternum to silence and disable her. She pushed past Rien—she had merely reached over her before—and snatched the stunner from the guard's belt. A quick reversal, the ozone scorch of a bridging spark, and the guard went down.

A good technology. So much safer than anything equally incapacitating Perceval could have done with her hands.

Briefly, she thought of murder. Her hands itched for the wash of blood. But this blood was not the blood she wanted.

"Run," she said, and grabbed Rien's wrist again. "Run! Lead me to an air lock. Run!"

Rien stared at her, blinked, blinked at the woman on the floor—then caught her hand in turn and pulled her on.

Good. Good, because Perceval needed it* Needed the hand and the tug, needed the other woman's strength to keep her moving. She had no momentum of her own. Every lifted foot was dragged as if through porridge. The gravity pulled like hands.

They had been running some ninety-three seconds by Perceval's atomic clock when the shriek of alarms began.

"Oh, space," Rien swore, and then covered her mouth with her hand. Were they so strict of their speech in Rule, then? Perceval forced her feet to lift, fall, lift again as fluid soaked her bandages, slicked the inside of the imporous dress. "They'll turn off the hydraulics. We won't be able to open the lock. And I can't go Outside anyway. I haven't a suit. We haven't a go-pack."

"We've my dress," Perceval said. "It'll do."

"I can't breathe vacuum." Rien let go Perceval's fingers, slumped against the corridor wall.

Perceval staggered two steps past her, turned, and caught herself on a twist of ductwork when she almost fell. But she lifted her eyes to Rien's and met them. "Where's the bck, Rien?"

"Aren't you listening?"

"Rien."

Rien rolled her eyes, shoved her frizzing tangles off her face, and jerked her chin down a side corridor. "Here."

"Come on." Perceval was dragging Rien again, but once she turned the corner she could see the massive vault door of the air lock. It gave her strength. They were alone in the corridor, though the wail of the siren and the thump of emergency lights on her retinas made her shudder with adrenaline.

Perceval grabbed the great old use-polished wheel on the air-lock door and twisted. Rien, surprising her, grabbed and strained as well. "Told you," she said, when the weight resisted them. But then she gasped, and leaned into it harder, as—under Perceval's strength, even without mechanical assistance—the lock began to turn.

Perceval might be light as a ghost, made of twigs and wire. But she was Exalt, daughter of Engineers and the House of Conn, and there was machine strength in her blood. From behind them, she heard running footsteps. She ducked her head and covered Rien with her body as a needle-gun sprayed the bulkhead.

The flesh of her palms broke open on the steel. But that steel yielded and, by inches, the door—thicker than her waist—cracked open. She dropped one arm around Rien and pulled her through and in.

Sealing the door was easier. She thought she felt hands fighting her as she dogged and locked it, but there was an emergency override, and she slapped it. Spring-loaded, ceramic bolts shot home, the impact shivering through the walls of the world.

One would need to cut through to open the interior door.

"Safe," Perceval said, and sagged against the wall for a moment. The pain of the contact shocked her back to her feet; she had forgotten the wounds. When she lurched forward she tripped and would have fallen if Rien had not steadied her. Without her wings, she was a

wkward and easily overbalanced.

"Trapped," Rien replied, turning to look at the exterior door. Her shoulders hunched. She knotted her hands together. "We don't keep suits in the locks. I told you."

"You won't need a suit," Perceval said, "if you will trust me."

"Trust you to what?"

"Exalt you." Perceval stroked Rien's arm. The flesh felt cool under the cardigan, but Perceval thought that was just her own fever.

"Infect me?" Rien turned, abruptly, light on the balls of her feet, and backed away from Perceval's touch. "You want to colonize me."

Perceval shrugged. "You've the blood to sustain it. You're old enough. You should have received a colony years ago. And it will keep you alive"—a gesture at the exterior air-lock door—"Outside."

Rien had put her back to the Outside. And on the inside door, Perceval now heard rhythmic hammering.

"What if I'm not?"

"Not?"

"Not your sister." She shook her head, her hair moving on her neck the way Perceval's once had. "Not Benedick's daughter."

Perceval could not help herself. She spread out her hands, palms toward Rien, and tilted her head. "Then it will kill you, Mean."

Rien gestured over Perceval's shoulder. "And so will they."

"Yes."

"Fine then," Rien said, all hollow bravado, and stepped forward into Perceval's arms.

Rien thought it would hurt. She imagined it would be hard, the initiation, that there would be some sense of transformation or wildfire intimation of change.

Not so.

Perceval embraced her, and she smelled the blood and the antiseptic, and when she lowered her mouth over Rien's, Rien tasted the faint sourness of uncleaned teeth. One would think her colony would take care of that for her, but then, it had perhaps been busy.

The kiss was long and soft, fever-hot and gentle, although holding Perceval in her arms was not unlike embracing a rope ladder. Her lips were soft and cracked over the firmness of her teeth, and it seemed as if Rien expanded on her breath like a blown balloon. Rien was reminded that she had always preferred young women.

She giggled, embarrassed, and stepped back—

—and felt, of a sudden, not outside herself, but rather inside herself as she had never felt before. It snapped in, as a whole, abrupt and perfect, the image and awareness of every nerve and every cell. She felt the colony engage her, accept her, rush with each beat of her heart on oxygenated blood to every extremity.

It felt curiously natural.

"Oh," she said.

"Breathe deep." Perceval was fiddling with the key, reshaping her dress into something else. A propulsion pack.

"Let the colony get as much oxygen as it can. We should have about fifteen minutes. I can get us out of Rule in fifteen minutes, and safe back inside."

If it was bravado, Rien would rather not know. "What about the cold?" she asked. "And ebullism?"

"Don't worry; your colony can maintain pressure. It will keep your eyeballs from freezing or your fluids from boiling until long after we run out of oxygen."

"Oh. Good to know."

Perceval laughed. "Hold onto my harness. I'm going to break the door open now. I won't be able to talk to you once we're outside, so just—-for the love of all your ancestors, when we get out there—hang on."

Hold on. Breathe deep.

Simple enough.

When the massive door swung open, though, and the puff of escaping air sailed them grandly into the crooked sunlight between the world's vast webworked cables, Rien forgot anything but the cold black fire-pricked vault of the universe stretching out forever, and the wheeling world that framed it on each side.

6 the beast in the heart of the world

In the sweat of thy fate shalt thou eat bread, till thou return unto the ground; but out of it wast thou taken: dust thou art, yet absent dust shalt thou be exalted.

—GENESIS 3:19, New Evolutionist Bible

Everyone else had forgotten, or was forbidden from remembering, which came to the same thing. Dust had never been human, but he remembered.

He remembered more of being human than the humans did. He contained novels and dramas, actors and singers, stories long untold. He contained histories dead a thousand Earth years. Dead to the world, anyway.

The same thing. The same.

No one in the world had seen a single yellow sun, dug fingers into crumbling natural earth, felt an acid rain trace down her face. Dust had never seen, felt, tasted any of these things either. But he recollected them.

In proper terms, he could not see, feel, taste in any case. But he could approximate. Smell was only a matter of detecting and sorting drifting molecules. Seeing was only a matter of detecting and sorting bounced light.

And what he could not approximate, he could remember.

"The world is mine," said Jacob Dust. "Mine. It has my name on it."

No argument.

No answer.

He hadn't expected one.

Dust hung in soft threads all through the atmosphere of his domaine. It was mostly water vapor now; the world had healed its wounds, and as Dust's need for the luxuries necessary to carbon-based life was small, he did not trouble himself to normalize.

Too much oxygen would only encourage the mortal and unmodified to seek him, anyway.

Dust believed in conserving resources. Energy came from the suns, a vast crimson sphere and a tiny white dwarf that whipped about their common center of gravity with a rotational period of only hours, tethered by a luminous banner dragged from the former, accreting to the latter. Material resources were more limited: only what was in the world, and what the world was made of. But Dust's years were long, and the suns burned bright.

By that brightening, he knew the hours of his safety were numbered. The dwarf star had entered its period of convection. At any point, it might commence a deflagration phase, fusing carbon and then oxygen.

Because the integrity of a dwarf star was dependent on the quantum degeneracy pressure of the core, it would be unable to expand and cool to maintain stability in response to an increase in thermal energy caused by accretion, as a main-sequence star would.

Within seconds, a considerable portion of the carbon and oxygen within the star would be fused into heavier elements. Because the star was supported by degenerate pressure rather than by thermal pressure, this thermonuclear event would cause the core temperature to skyrocket—to employ an entirely inadequate metaphor—by billions of degrees, causing further fusion.

The sun would unbind.

The white dwarf would explode, its outer layers hurled clear in a single apocalyptic paroxysm, a shock front moving at nearly 3 percent the speed of light. In a flare of brilliance that would outshine entire galaxies fiftyfold, the world would end.

The sunlight that warmed Dust, which fed all his inhabitants, heralded the furnace that would burn him. And through that sunlight hurtled a pair of half-grown women, whom Dust watched with amusement and a bit of approval. When the angels were otherwise occupied, he could still use their thousands of eyes, all over the skin of the world.

Those eyes showed him Perceval, Rien clutched in her arms, gliding soundlessly across the hub of the turning world. The go-pack on her back trailed wisps of vapor, a trickle of reactive mass. The sort of thing one usually avoided sacrificing to the great cold Enemy, but then, one made exceptions in an emergency. A sacrifice. A burnt offering to Entropy.

Which, like most gods, took no notice.

Dust was different from other gods. And he was not particular about the intended consecration. It attracted his attention—well, to be fair, his attention had been held already—and that was enough.

Dust could not reach Perceval's colony. It would not see him; it would not hear him. It was blinded and deafened to any of his blandishments. He could not see through her eyes, speak through her lips. She possessed it fully, and all its service, and Rien's new daughter-colony was likely forbidden to Dust as well, and would only grow more so

as Rien mastered it, and imprinted it with her personality.

But the chains that had become a dress and which now were a simple propulsion device, trickling pressurized atmosphere—that colony had no guiding intelligence.

Dust reached out through wireless connections, through the constant soft hum of telemetry in which the world floated, embedded. He saw as the colony saw—not that it was seeing, exactly. He tasted Perceval's skin, felt her fever-heat (she was very brave, and very ill), felt the bones and skin pressed to the go-pack like a man might feel a lover's spine pressed to his chest. He felt Rien's hands clenched on his straps as she clung against Perceval's chest, shivering and awed.

Like a man waking a child who must not cry out, Dust tickled the edges of the go-pack colony. It was stupid, lobotomized, an idiot system. He made it whole, alert, aware. It was fit only for following orders. He gave it autonomy—of a sort.

Perceval and Rien passed under the stark shadows of the cabling, which with no atmosphere to refract or soften the light remained razor-edged upon their skin. They passed by the hub of the world, where Dust's house was, and where the abandoned bridge moldered. Rien's eyes moved as she read the gold and black lettering upon the hull.

Jacob's Ladder.

Behind the words was painted a double helix, green and yellow, red and white and blue.

"This is my world," said Jacob Dust, as they passed the skin of his domaine, Perceval and Rien in the arms of his newborn son. "My world. My name."

Phantom pain.

It was only phantom pain. Except it wasn't pain, exactly, because it didn't hurt. Rather, Perceval thought she felt her wings stretch and cup, pulling against the knotted, insulted muscles of her chest and back.

It must be only the cold of space on her unhealed wounds, the severed nerves and the reprogramming damage of the unblade. It was still bleeding, she thought, her blood and her colony still groping for lost members and severed flesh. She would have to make it stop bleeding somehow. She would have to heal the unhealable wound.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

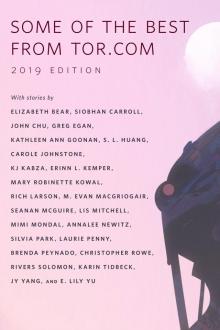

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

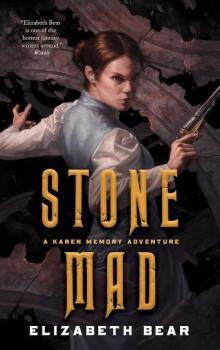

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

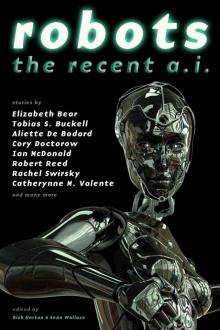

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3