- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Grail jl-3 Page 4

Grail jl-3 Read online

Page 4

Gain offered Amanda a respectful nod. Amanda returned it. “Research is my primary. Driving spaceships is a tertiary, but I need it for my work.”

“Well done,” Gain said.

Amanda looked down. “There are risks to sending out a scull—and even bigger risks to boarding the ship, if that is the choice we make. Debris, antagonizing any residents, contagion. I would recommend drones before any manned mission, although we should limit those contacts. Drones can seem quite threatening.”

Gain turned from the waist to face Danilaw directly. “You mentioned that they are still using radio broadcast technology. You may not know that there is a culture of radio hobbyists here on Fortune who still play with primitive equipment. I know a few; I think they could be brought in as consultants. We could contact them in advance.”

Jesse made a noise of agreement. Gain, finished speaking, seemed to be taking notes on her infothing. Amanda lifted a jug of water from the surface of the table, leaving a ring of condensation.

As she poured, she resumed. “I speak the language, though—or I speak the language they used when they left Earth. But as you can imagine, it’s been centuries for them as well, and no doubt the language has diverged.”

Danilaw spoke the tongue, too, or had accrued a tolerable understanding over the years, given how he fulfilled the arts requirement of his Obligation. A significant fraction of the seminal twentieth- and twenty-first-century rock and roll was in English, and the people consigned to—or escaping in—the Jacob’s Ladder had spoken primarily that language.

He’d have to arrange backup childcare for his sister’s kids, but that was a minor inconvenience. He could go.

“The good news,” Gain said, “is they don’t seem to be sneaking. But that doesn’t explain why they haven’t hailed us. If they had, those radio operators I mentioned would be talking of nothing else.”

Danilaw pulled another glass over and pushed it toward Amanda with his fingertips. She finished with her own and filled it without looking up, then offered the pitcher to Gain and Jesse. Jesse accepted and filled two more cups.

Danilaw drank and spoke. “There’s a possibility they don’t know we’re here. Remember, they left Earth just at the beginning of the quantum revolution. They should have artificial gravity, but we can’t be sure what directions their research will have taken since then—assuming they have advanced and not regressed. They are broadcasting on radio frequencies, which means they’re subject to lightspeed lag. And if they’re looking for evidence of habitation on those same frequencies, they won’t find anything. Or at least, not much—I assume your friends are a small group?”

“Not the biggest,” Gain admitted with a smile. “There’s a few dozen of us.”

“They may not even be looking.” Amanda set her water glass down and twirled it between her fingers. “Why would they expect us to have leapfrogged them? When they left Earth, its society seemed more likely to knock itself back to the Paleolithic—if it was lucky—rather than survive into the quantum age. As far as they know, they fled a smoking cinder, a world rendered uninhabitable by ecological collapse.”

Her words fell into a silent room. Jesse fidgeted. Gain leaned forward on her elbows and, after a few moments, quietly said, “Will they want to fight us?”

Danilaw rolled his cup between his hands, stopping when the bottom squeaked painfully on the tabletop. “I don’t know,” he said. “Possibly.”

4

a library once

Though he heap up silver as the dust, and prepare raiment as the clay; He may prepare it, but the just shall put it on, and the innocent shall divide the silver.

—Job 27:16–17, King James Version

Benedick watched the recording of the captured probe twice, leaning over Caitlin’s shoulder, trying not to think about the smell of her hair. So many mistakes; so many regrettable events in an existence measured in centuries. You never stopped wondering what might have been different.

Even now, with incontrovertible evidence of aliens—human aliens, admittedly, and not so alien as Leviathan, but almost certain to prove weirder than all the nonhuman intelligences that filled up the walls of the world—Benedick found Cat’s presence a reminder of all the errors of a long life. The years and the work had eased things between them, and they were friends again, which was good, because they needed to be able to work together.

But he missed her, as simply as that. And he had never quite stopped wanting her back.

Still, he’d settled for what he could earn, and reconstructing the friendship had also served to reconstruct the trust. He didn’t think there were many people she’d allow to stand over her like this so calmly, invading her personal space while she worked.

He straightened up and came around the display tank to face her. “We can’t assume their intentions,” he said quietly, when he knew he had her attention. It was just a shift of the eyes, but it was enough. They were still a team.

“You’re worried about what will happen when we start exchanging diplomats.”

He shrugged, brushing his hair behind his shoulders. “Nanotechnology, inducer viruses—or whatever they have that’s similar—bacterial agents, engineered or accidental. There’s no telling what could come in on their shoes. And we can’t assume, after centuries of isolation, that we have any reciprocal immunities.”

“And they’re very likely to be Means,” Caitlin said. “Our bugs might just kill them—not to mention the colonies. Are they going to want to become Exalt?”

“It’s something we can bargain with,” Benedick said. “It’s an advantage and possibly a trade good.”

“But it’s combat you’re worried about.”

He felt himself smile. As well as he knew her, it was reciprocated. “Combat. Or treachery.”

She had a peculiar gesture of rubbing her nose that was all hers. “Well, you are our father’s son.”

Benedick folded his hands under his arms. Don’t remind me. “Yes, he would have assumed the worst. But that does not universally indicate that he would have been wrong.”

Her mouth worked around whatever she was thinking of saying. Because it was Caitlin, he would never know how many options she chewed over and discarded before she settled. “I am sorry,” she said. “I was trying to provoke you.”

That he could smile for. “Cheap sport,” he said. “I’d have thought such an easy opponent beneath you.”

She stood and punched him lightly on the shoulder. “I’ve got to keep in trim for the aliens. So what do we recommend to the Captain?”

The Captain, their daughter. “We’re going to have to meet with them,” Benedick said. “Especially when we’re asking to share a planet, because I don’t think they’ll cede either of those two potentially habitable worlds to us entirely. It’s not human nature.”

“So even if they are inhumanly gracious, we’re going to have to live with them.”

“And when we do, we need to be aware of and guarded against all the possibilities for disaster.”

Caitlin turned her head, glancing over her shoulder at the system diagrams spinning with stately indifference in the big image tank. “I hope we’re aware of that,” she said. “I hate to think we’re underselling it to ourselves.”

Very little in the world knows more about keeping quiet than does a library.

Dust, who had been a library once, huddled in his ringspotted fur coat, paws dry-washing, all the active senses that might have told him enough about his environment to move in safety drawn inward, turned passive, locked down. He felt the new Angel all around, the web of her presence a veil made of trip wires and snares. If she found him she would eat him, as she had eaten most of him already. As she had eaten every other angel and remnants of angels she had found. If she found him, she would devour him whole. So, with perfect logic, he decided she would not find him at all.

The world had changed from what he knew. While he died, slept, and grew back from a spark, it had evolved from a hulk to a hav

en, from a shell to a ship.

Who had preserved the spark of him? And who had caused it to awaken here, into the helpful-animal consciousness of this furry toolkit with its deft hands and keen, twitching nose?

And who had thought that this, the eve of landfall, would be an opportune time to return him from the quiet cold of storage?

It seemed to Dust that, first, he must learn who had preserved him, and what that person or those persons intended. And then, having done that, he must decide how he was going to use those intentions to suit his own designs.

Dust was small now. Dust scurried. Dust moved without notice through the channels in the walls of the world. Dust only half recollected himself, but from what he remembered of the angel he had been, he would have left himself resources. Resources baled, blindered, and buried against future need. He had always been a hoarder—that was also after the nature of libraries.

His spotted pink and brown nose twitched. He sniffed, careful of whose spores he brought into the lungs of his insufficient, temporary form. If he could not extend his senses out into the world for fear of drawing the new Angel’s attention, he’d bring the world into himself and parse it that way. Primitive, but it should be effective enough if he were painstaking and meticulous.

He’d find the resources. He’d answer the questions. He’d learn who had brought him back.

He’d reclaim his ship, and he’d win his freedom again.

Dust filtered mouse-soft into the cracks in the walls and was gone.

Caitlin Conn did not have to travel from Engine to the Bridge to speak to, or even to see, her daughter. But she often did, walking down the long corridor past the venerable New Evolutionist Bible and climbing through the irising door to the Bridge before it was entirely open, and for this Perceval was grateful. The loneliness of command was one thing, and the loneliness of missing your family quite another. And seeing and speaking weren’t the same thing as physical contact, oxytocin, pheromones—the bonding chemicals that managed stress and settled cortisol levels.

Perceval managed her own neurochemistry through her symbiont, but manual manipulation of any system so complex, nuanced, and responsive was inevitably cruder and more granular than what the healthy brain managed on its own, with the proper stimulus.

And sometimes it was nice to see her mother and collect a hug.

Caitlin arrived dressed for off-duty, which was another endocrine signal Perceval didn’t get enough of. When the Bridge door dilated to reveal Caitlin’s broad-hipped, broad-shouldered form in blousing trousers and barefoot, it was as if somebody had pulled a plug in Perceval’s spine and let all the stress run out.

To puddle on the floor, she thought, with a grimace. Where you will have to mop it up later.

The Captain kept the cynicism out of her voice as she said, “Hey, Mom.”

She hadn’t thought she was trying to sound particularly nonchalant, but if the words had come out that way, Caitlin wasn’t buying it. She cleared the doorway quickly and stood just inside while it sealed, hands on her hips and head cocked appraisingly. Caitlin still wore her black unblade, Charity—but there was off-duty, and there was stupidity.

Although Perceval stood still to greet her, her white trousers and shift falling about her with folds unstirred even by the movement of air, Caitlin huffed and glanced around the Bridge as if she could see every moment of Perceval’s last hour.

And perhaps she could, if she were checking in the infrared. The cold Captain’s chair, and the warmth of footsteps sprinkled over the grass and meadow flowers of the Bridge decking. The evidence of Perceval’s tight-reined distress lay everywhere.

“Wearing a groove in the planking?” Caitlin said. Grass whisked between her toes as she came to her daughter. Perceval might be taller, but Caitlin still outmassed her by half. She hunched herself down to accept her mother’s hug, wishing to feel enfolded in it, protected. Nobody could be impervious all the time. Except, Perceval thought ruefully as she straightened, possibly Benedick.

“Pacing the Bridge is the Captain’s prerogative,” Perceval said.

In old days, the Bridge would have been a gathering place for senior crew. But the Jacob’s Ladder was alive now, and the world’s control center could be wherever Perceval went. The Bridge was now her retreat, her hermitage.

And like all such places, it could be painfully lonely.

“And provoking the Captain is the Chief Engineer’s,” Caitlin replied. She plunked herself unceremoniously on the grass and stretched out. “Nova, amplified sunlight, please.”

Perceval’s pupils contracted, cones swelling to replace rods in her eyes as the wide windows arching across the surface of the sky paled and depolarized, screens sliding back to widen the apertures. Elements of the world’s halo of symbiotic nanocolonies—which also, along with its ramscoop and other electromagnetic fields, served to insulate it from space debris—became reflective and refractive. Biomimetic sensors in the ship’s colony cloud, and on her hull, helped the prisms and mirrors train themselves on the distant star, gathering its light. Like a sunflower, the Jacob’s Ladder focused itself on distant warmth.

The Bridge shivered with radiation—alien comfort after so many years in the dark.

Perceval was also still getting used to living in a world where more things worked than didn’t.

Caitlin patted the gentle swell of the bank beside her. “Sit, child. Enjoy the light.”

Perceval sat. She composed herself and reclined beside her mother, closing her eyes. But she did not close off the datastreams that painted the inside of her head with a constant flow of information, making her eyes largely extraneous for most purposes more complex than—well—navigating around a room.

She sighed, knowing Caitlin would read the complex of emotions in it—contentment, distress—and also knowing that Caitlin, being a mother, would ask.

Predictability in a parent was a good thing.

“Out with it,” Caitlin said. “What troubles you? Our journey is at an end, our rest in sight. Or rather, different work confronts us, but with luck and the cooperation or capitulation of the current residents, we can fold this world up and live someplace a little easier to maintain.”

“A planet is a closed ecology, too, Mother,” Perceval said. “Do you really think it will be easier to maintain? We know how the world works. We have no idea how we’ll interact with a planet.”

Natural ecologies were famously fragile, easy to overset—as Earth’s had been.

“We’ll do the best we can,” Caitlin said. “But is that really what’s bothering you? A question of environmental ethics?”

Perceval sighed, though this time it was to buy time, not to invite her mother in. The radiation on her face did feel good. She could feel the ancient evolved systems of her body responding, producing melanin and vitamin D, her muscles relaxing in the heat, her digestion becoming more efficient. Her stomach grumbled quietly and she smiled.

“No,” she said. “I miss Rien. Right now—” She stretched her back against the grass, the smell of chlorophyll and bruised flower petals rising around her. “I wish Rien were here to see this.”

Caitlin’s hand stole out to brush Perceval’s, first back to back and then clasping fingers. “You are not alone.”

Perceval sat up, hunching forward over her hollow belly, and disentangled her fingers from her mother’s. She hugged her knees tight and pulled her forehead almost down to her shins. “Sometimes I wish I were.”

She wasn’t expecting Caitlin’s bark of laughter. One of the joys of adulthood was dealing with her mother as a peer, as an ally and a friend.

“Sir Perceval,” Caitlin said, invoking a title Perceval had not heard often since she first sat in the Captain’s chair. From the change in her voice and the rustle of grass, Perceval knew that Caitlin sat up, too. “You have never stopped being a knight-errant, my dear. Did you go looking for her?”

Did you go looking for Rien’s remains in Nova? was what Caitlin meant. Had P

erceval sieved through the Angel’s personality for the fragments that had once been Rien, to reassemble them into some parody of her beloved, much as Cynric was—according to Tristen—a sort of parody of what she once had been?

Perceval wasn’t sure if she shook her head slightly or if it was a pressure change that ruffled her hair. She tossed it back, swinging herself again into a sitting position, and shook the brown locks down her shoulders like a snapped-out banner. “I would not have liked what I found.”

“Wise child,” Caitlin said, and kissed her on the top of the head.

Perceval exhaled a breath she did not remember holding. But before she could take in another, Nova’s voice broke the stillness and insect-drone of the meadow. The words sounded to Perceval’s inner and outer ears simultaneously.

“Captain, Chief Engineer. Five intruders have accessed the Bridge corridor. I have called for support and await your recommendation.”

Perceval found herself on her feet, her mother beside her. “How did intruders penetrate this far? Nova, the approaches are full of your colony corona.”

“Unknown,” Nova said.

Caitlin drew out her unblade. In the loudness of Perceval’s heart, it made no sound at all. Her voice rang clean across the Bridge, however, just as if more than one ear must hear her commands. “For any defensive technology, there is an equal and opposite countermeasure.”

“Great,” Perceval said. “They’ve hacked through it somehow. Nova, my armor please?”

The suit was in the Bridge closet. It was a trivial matter for Nova to disassemble it there and reassemble the component molecules in their proper configurations around Perceval while Perceval held her breath and stilled her movements. Caitlin’s was a little more complex, as she’d left the physical suit in Engineering, so the Angel must pattern it and reconstitute it from available materials here.

“Are they attempting to broach the Bridge?” Perceval asked, as Caitlin’s vermilion-and-gold armor began to take shape around her.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

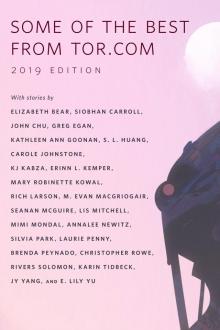

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

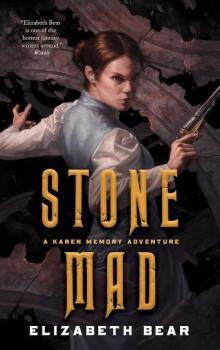

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3