- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Page 4

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Read online

Page 4

Unexpectedly, Victor’s crew seemed glad to be shut in more securely. They moved most activities to the upper floor of the front wing, avoiding the shuttered darkness downstairs. They went to bed earlier to conserve candles. They partied in the dark.

The electric pumps had stopped, but an old hand-pump at the basement laundry tubs was rigged to draw water from the well into the pipes in the house. They tore up part of the well yard in the process, getting dust everywhere, but in the end they even got a battered old boiler working over a wood-fire in the basement. A bath rota was eagerly subscribed to, although Alicia, the wig-girl, was forbidden to use hot water to bathe her Yorkie any more.

Victor rallied his troops that evening. He was not a tall man but he was energetic and his big, handsome face radiated confidence and determination. “Look at us—we’re movie people, spinners of dreams that ordinary people pay money to share! Who needs a screening room, computers, TV? We can entertain ourselves, or we shouldn’t be here!”

Sickly grins all around, but they rose at once to his challenge.

They put on skits, plays, take-offs of popular TV shows. They even had concerts, since several people could play piano or guitar well and Walter was not the only one with a good singing voice. Someone found a violin in a display case downstairs, but no one knew how to play that. Krista and the youngest of the cooks told fortunes, using tea leaves and playing cards from the game room. The fortunes were all fabulous.

Miriam did not think about the future. She occupied herself taking pictures. One of the camera men reminded her that there would be no more recharging of batteries now; if she turned off the LCD screen on the Canon G9 its picture-taking capacity would last longer. Most of the camcorders were already dead from profligate over-use.

It was always noisy after sunset now; people fought back this way against the darkness outside the walls of La Bastide. Miriam made earplugs out of candle wax and locked her bedroom door at night. On an evening of lively revels (it was Walter’s birthday party) she quietly got hold of all the keys to her room that she knew of, including one from Bulgarian Bob’s set. B. Bob was busy at the time with one of the drivers, as they groped each other urgently on the second floor landing.

There was more sex now, and more tension. Fistfights erupted over a card game, an edgy joke, the misplacement of someone’s plastic water bottle. Victor had Security drag one pair of scuffling men apart and hustle them into the courtyard.

“What’s this about?” he demanded.

Skip Reiker panted, “He was boasting about some Rachman al Haj concert he went to! That guy is a goddamn A-rab, a crazy damn Muslim!’

“Bullshit!” Sam Landry muttered, rubbing at a red patch on his cheek. “Music is music.”

“Where did the god damned Sweat start, jerk? Africa!” Skip yelled. “The ragheads passed it around among themselves for years, and then they decided to share it. How do you think it spread to Europe? They brought it here on purpose, poisoning the food and water with their contaminated spit and blood. Who could do that better than musicians ‘on tour’?”

“Asshole!” hissed Sam. “That’s what they said about the Jews during the Black Plague, that they’d poisoned village wells! What are you, a Nazi?”

“Fucker!” Skip screamed.

Miriam guessed it was withdrawal that had him so raw; coke supplies were running low, and many people were having a bad time of it.

Victor ordered Bulgarian Bob to open the front gates.

“Quit it, right now, both of you,” Victor said, “or take it outside.”

Everyone stared out at the dusty row of cars, the rough lawn, and the trees shading the weedy driveway as it corkscrewed downhill toward the paved road below. The combatants slunk off, one to his bed and the other to the kitchen to get his bruises seen to.

Jill, Cameron’s hair stylist, pouted as B. Bob pushed the heavy front gates shut again. “Bummer! We could have watched from the roof, like at a joust.”

B. Bob said, “They wouldn’t have gone out. They know Victor won’t let them back in.”

“Why not?” said the girl. “Who’s even alive out there to catch the Sweat from anymore?”

“You never know.” B. Bob slammed the big bolts home. Then he caught Jill around her pale midriff, made mock-growling noises, and swept her back into the house. B. Bob was good at smoothing ruffled feathers. He needed to be. Tensions escalated. It occurred to Miriam that someone at La Bastide might attack her, just for being from the continent on which the disease had first appeared. Mike Bellows, a black script doctor from Chicago, had vanished the weekend before; climbed the wall and ran away, they said.

Miriam saw how Skip Reiker, a film editor with no film to edit now, stared at her when he thought she wasn’t looking. She had never liked Mike Bellows, who was an arrogant and impatient man; perhaps Skip had liked him even less, and had made him disappear.

What she needed, she thought, was to find some passage for herself, some unwatched door to the outside, that she could use to slip away if things turned bad here. That was how a survivor must think. So far, the ease of life at La Bastide—the plentiful food and sunshine, the wine from the cellars, the scavenger hunts and skits, the games in the big salon, the fancy-dress parties—had bled off the worst of people’s edginess. Everyone, so far, accepted Victor’s rules. They knew that he was their bulwark against anarchy.

But: Victor had only as much authority as he had willing obedience. Food rationing, always a dangerous move, was inevitable. The ultimate loyalty of these bought-and-paid-for friends and attendants would be to themselves (except maybe for Bulgarian Bob, who seemed to really love Victor).

Only Jeff, one of the drivers, went outside now, tinkering for hours with the engines of the row of parked cars. One morning Miriam and Krista sat on the front steps in the sun, watching him.

“Look,” Krista whispered, tugging at Miriam’s sleeve with anxious, pecking fingers. Down near the roadway a dozen dogs, some with chains or leads dragging from their collars, harried a running figure across a field of withered vines in a soundless pantomime of hunting.

They both stood up, exclaiming. Jeff looked where they were looking. He grabbed up his tools and herded them both back inside with him. The front gates stayed closed after that.

Next morning Miriam saw the dogs again, from her balcony. At the foot of the driveway they snarled and scuffled, pulling and tugging at something too mangled and filthy to identify. She did not tell Krista, but perhaps someone else saw too and spread the word (there was a shortage of news in La Bastide these days, as even radio signals had become rare).

Searching for toothpaste, Miriam found Krista crying in her room. “That was Tommy Mullroy,” Krista sobbed, “that boy that wanted to make computer games from movies. He was the one with those dogs.”

Tommy Mullroy, a minor hanger-on and a late riser by habit, hadn’t made it to the cars on the morning of Victor’ hasty retreat from Cannes. Miriam was doubtful that Tommy could have found his way across the plague-stricken landscape to La Bastide on his own, and after so much time.

“How could you tell, from so far?” Miriam sat down beside her on the bed and stroked Krista’s hand. “I didn’t know you liked him.”

“No, no, I hate that horrible monkey-boy!” Krista cried, shaking her head furiously. “Bad jokes, and pinching! But now he is dead.” She buried her face in her pillow.

Miriam did not think the man chased by dogs had been Tommy Mullroy, but why argue? There was plenty to cry about in any case.

Winter had still not come; the cordwood stored to feed the building’s six fireplaces was still stacked high against the courtyard walls. Since they had plenty of water everyone used a lot of it, heated in the old boiler. Every day a load of wood ash had to be dumped out of the side gate.

Miriam and Krista took their turns at this chore together.

They stood a while (in spite of the reeking garbage overflowing the alley outside, as no one came to take it away any more).

The road below was empty today. Up close, Krista smelled of perspiration and liquor. Some in the house were becoming neglectful of themselves.

“My mother would use this ash for making soap,” Krista said, “but you need also—what is it? Lime?”

Miriam said, “What will they do when all the soap is gone?”

Krista laughed. “Riots! Me, too. When I was kid, I thought luxury was change bedsheets every day for fresh.” Then she turned to Miriam with wide eyes and whispered, “We must go away from here, Mimi. They have no Red Sweat in my country for sure! People are farmers, villagers, they live healthy, outside the cities! We can go there and be safe.”

“More safe than in here?” Miriam shook her head. “Go in, Krista, Victor’s little boys must be crying for you. I’ll come with you and take some pictures.”

The silence outside the walls was a heavy presence, bitter with drifting smoke that tasted harsh; some of the big new villas up the valley, built with expensive synthetic materials, smoldered slowly for days once they caught fire. Now and then thick smoke became visible much further away. Someone would say, “There’s a fire to the west,” and everyone would go out on the terrace to watch until the smoke died down or was drifted away out of sight on the wind. They saw no planes and no troop transports now. Dead bodies appeared on the road from time to time, their presence signaled by crows calling others to the feast.

Miriam noticed that the crows did not chase others of their kind away but announced good pickings far and wide. Maybe that worked well if you were a bird.

A day came when Krista confided in a panic that one of the twins was ill.

“You must tell Victor,” Miriam said, holding the back of her hand to the forehead of Kevin, who whimpered. “This child has fever.”

“I can’t say anything! He is so scared of the Sweat, he’ll throw the child outside!”

“His own little boy?” Miriam thought of the village man who drove out his son as a witch. “That’s just foolishness,” she told Krista; but she knew better, having known worse.

Neither of them said anything about it to Victor. Two days later, Krista jumped from the terrace with Kevin’s small body clutched to her chest. Through tears, Miriam aimed her camera down and took a picture of the slack, twisted jumble of the two of them. They were left there on the driveway gravel with its fuzz of weeds and, soon after, its busy crows.

The days grew shorter. Victor’s crowd partied every night, never mind about the candles. Bulgarian Bob slept on a cot in Victor’s bedroom, with a gun in his hand: another thing that everyone knew but nobody talked about.

On a damp and cloudy morning Victor found Miriam in the nursery with little Leif, who was on the floor playing with a dozen empty medicine bottles. Leif played very quietly and did not look up. Victor touched the child’s head briefly and then sat down across the table from Miriam, where Krista used to sit. He was so cleanshaven that his cheeks gleamed. He was sweating.

“Miriam, my dear,” he said, “I need a great favor. Walter saw lights last night in the village. The army must have arrived, at long last. They’ll have medicine. They’ll have news. Will you go down and speak with them? I’d go myself, but everyone depends on me here to keep up some discipline, some hope. We can’t have more people giving up, like Krista.”

“I’m taking care of Leif now—” Miriam began faintly.

“Oh, Cammie can do that.”

Miriam quickly looked away from him, her heart beating hard. Did he really believe that he had taken his current wife into La Bastide after all, in her spangly green party dress?

“This is so important,” he urged, leaning closer and blinking his large, blue eyes in the way that (B. Bob always said) the camera loved. “There’s a very, very large bonus in it for you, Miriam, enough to set you up very well on your own when this is all over. I can’t ask anyone else, I wouldn’t trust them to come back safe and sound. But you, you’re so levelheaded and you’ve had experience of bad times, not like some of these spoiled, silly people here. Things must have gotten better outside, but how would we know, shut up in here? Everyone agrees: we need you to do this.

“The contagion must have died down by now,” he coaxed. “We haven’t seen movement outside in days. Everyone has gone, or holed up, like us. Soldiers wouldn’t be in the village if it was still dangerous down there.”

Just yesterday Miriam had seen a lone rider on a squeaky bicycle peddling down the highway. But she heard what Victor was not saying: that he needed to be able to convince others to go outside, convince them that it was safe, as the more crucial supplies (dope, toilet paper) dwindled; that he controlled those supplies; that he could, after all, have her put out by force.

Listening to the tink of the bottles in Leif’s little hands, she realized that she could hardly wait to get away; in fact, she had to go. She would find amazing prizes, bring back news, and they would all be so grateful that she would be safe here forever. She would make up good news if she had to, to please them; to keep her place here, inside La Bastide.

But for now, go she must.

Bulgarian Bob found her sitting in dazed silence on the edge of her bed.

“Don’t worry, Little Mi,” he said. “I’m very sorry about Krista. I’ll look out for your interest here.”

“Thank you,” she said, not looking him in the eyes. Everyone agrees. It was hard to think; her mind kept jumping.

“Take your camera with you,” he said. “It’s still working, yes? You’ve been sparing with it, smarter than some of these idiots. Here’s a fresh card for it, just in case. We need to see how it is out there now. We can’t print anything, of course, but we can look at your snaps on the LCD when you get back.”

The evening’s feast was dedicated to “our intrepid scout Miriam.” Eyes glittering, the beautiful people of Victor’s court toasted her (and, of course, their own good luck in not having been chosen to venture outside). Then they began a boisterous game: who could remember accurately the greatest number of deaths in the Final Destination movies, with details?

To Miriam, they looked like crazy witches, cannibals, in the candlelight. She could hardly wait to leave.

Victor himself came to see her off early in the morning. He gave her a bottle of water, a ham sandwich, and some dried apricots to put in her red ripstop knapsack. “I’ll be worrying my head off until you get back!” he said.

She turned away from him and looked at the driveway, at the dust-coated cars squatting on their flattened tires, and the shrunken, darkened body of Krista.

“You know what to look for,” Victor said. “Matches. Soldiers. Tools, candles; you know.”

The likelihood of finding anything valuable was small (and she would go out of her way not to find soldiers). But when he gave her shoulder a propulsive pat, she started down the driveway like a wind-up toy.

Fat dogs dodged away when they saw her coming. She picked up some stones to throw but did not need them.

She walked past the abandoned farmhouses and vacation homes on the valley’s upper reaches, and then the village buildings, some burned and some spared; the empty vehicles, dead as fossils; the remains of human beings. Being sold away, she had been spared such sights back home. She had not seen for herself the corpses in sun-faded shirts and dresses, the grass blades growing up into empty eye sockets, that others had photographed there. Now she paused to take her own carefully chosen, precious pictures.

There were only a few bodies in the streets. Most people had died indoors, hiding from death. Why had her life bothered to bring her such a long way round, only to arrive where she would have been anyway had she remained at home?

Breezes ruffled weeds and trash, lifted dusty hair and rags fluttering from grimy bones, and made the occasional loose shutter or door creak as it swung. A few cows—too skittish now to fall easily to roaming dog packs—grazed watchfully on the plantings around the village fountain, which still dribbled dispiritedly.

If there were ghosts, they did not show t

hemselves to her.

She looked into deserted shops and houses, gathering stray bits of paper, candle stubs, tinned food, ballpoint pens. She took old magazines from a beauty salon, two paperback novels from a deserted coffee house. Venturing into a wine shop got her a cut on the ankle: the place had been smashed to smithereens. Others had come here before her, like that dead man curled up beside the till.

In a desk drawer she found a chocolate bar. She ate it as she headed back up the valley, walking through empty fields to skirt the village this time. The chocolate was crumbly and dry and dizzyingly delicious.

When she arrived at the gates of La Bastide, the men on watch sent word to Bulgarian Bob. He stood at the iron balustrade above her and called down questions: What had she seen, where exactly had she gone, had she entered the buildings, seen anyone alive?

“Where is Victor?” Miriam asked, her mouth suddenly very dry.

“I’ll tell you what; you wait down there till morning,” Bulgarian Bob said. “We must be sure you don’t have the contagion, Miriam. You know.”

Miriam, not Little Mi. Her heart drummed painfully. She felt injected into her own memory of Cammie and Paul standing here, pleading to come in. Only now she was looking up at the wall of La Bastide, not down from the terrace.

Sitting on the bonnet of one of one of the cars, she stirred her memory and dredged up old prayers to speak or sing softly into the dusk. Smells of food cooking and wood smoke wafted down to her. Once, late, she heard squabbling voices at a second floor window. No doubt they were discussing who would be sent out the next time Victor wanted news of the world and one less mouth to feed.

In the morning, she held up her arms for inspection. She took off her blouse and showed them her bare back.

“I’m sorry, Miriam,” Victor called down to her. His face was full of compassion. “I think I see a rash on your shoulders. It may be nothing, but you must understand—at least for now, we can’t let you in. I really do want to see your pictures, though. You haven’t used up all your camera’s battery power, have you? We’ll lower a basket for it.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

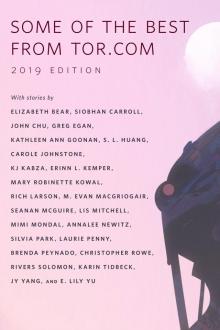

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

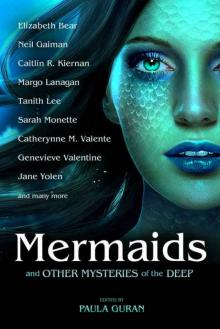

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

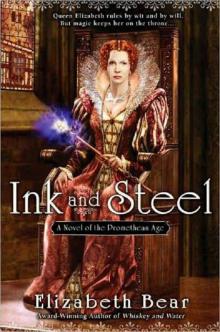

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3