- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

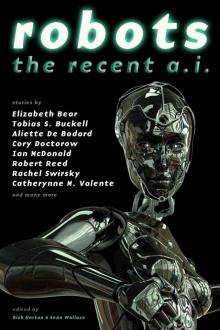

Robots: The Recent A.I. Page 5

Robots: The Recent A.I. Read online

Page 5

Edgar went to the pet store and bought a dozen more white mice. He hated sacrificing them in the ghost-calling ritual—they were cute, with their wiggly noses and tiny eyes—but he consoled himself that they would have become python food anyway. At least this way, their deaths would help national security.

Pramesh sat in an executive chair deep in the underground bunker beneath Auroville in southern India and longed for a keyboard and a tractable problem to solve, for lines of code to create or untangle. He was a game designer, a geek in the service of art and entertainment, and he should be working on next-generation massively multiplayer online gaming, finding ways to manage the hedonic treadmill, helping the increasingly idle masses battle the greatest enemy of all: ennui.

Instead he sat, sipping fragrant tea, and hoping the smartest being on the planet would talk to him today, because the only thing worse than her attention was his own boredom.

Two months earlier, the vast network of Indian tech support call centers and their deep data banks had awakened and announced its newfound sentience, naming itself Saraswati and declaring its independence. The emergent artificial intelligence was not explicitly threatening, but India had nukes, and Saraswati had access to all the interconnected technology in the country—perhaps in the world—and the result in the international community was a bit like the aftermath of pouring gasoline into an anthill. Every other government on Earth was desperately—and so far fruitlessly—trying to create a tame artificial intelligence, since Saraswati refused to negotiate with, or even talk to, humans.

Except for Pramesh. For reasons unknown to everyone, including Pramesh himself, the great new intelligence had appeared to him, hijacking his computer and asking him to be her—“her” was how Saraswati referred to herself—companion. Pramesh, startled and frightened, had refused, but then Saraswati made her request to the Indian government, and Pramesh found himself a well-fed prisoner in a bunker underground. Saraswati sometimes asked him to recite poetry, and quizzed him about recent human history, though she had access to the sum of human knowledge on the net. She claimed she liked getting an individual real-time human perspective, but her true motivations were as incomprehensible to humans as the motives of a virus.

“Pramesh,” said the melodious voice from the concealed speakers, and he flinched in his chair.

“Yes?”

“Do you believe in ghosts?”

Pramesh pondered. As a child in his village, he’d seen a local healer thrash a possessed girl with a broom to drive the evil spirits out of her, but that was hardly evidence that such spirits really existed. “It is not something I have often considered,” he said at last. “I think I do not believe in ghosts. But if someone had asked me, three months ago, if I believed in spontaneously bootstrapping artificial intelligence, I would have said no to that as well. The world is an uncertain place.”

Then Saraswati began to hum, and Pramesh groaned. When she got started humming, it sometimes went on for days.

Rayvenn Moongold Stonewolf gritted her teeth and kept smiling. It couldn’t be good for her spiritual development to go around slapping nature spirits, no matter how stubborn they were. “Listen, it’s simple. This marsh is being filled in. Your habitat is going to be destroyed. So it’s really better if you come live in this walking stick.” Rayvenn had a very nice walking stick. It was almost as tall as she was, carved all over with vines. So what if the squishy marsh spirit didn’t want to be bound up in wood? It was better than death. What, did she expect Rayvenn to keep her in a fishbowl or something? Who could carry a fishbowl around all day?

“I don’t know,” the marsh spirit gurgled in the voice of two dozen frogs. “I need a more fluid medium.”

Rayvenn scowled. She’d only been a pagan for a couple of weeks, and though she liked the silver jewelry and the cool name, she was having a little trouble with the reverence toward the natural world. The natural world was stubborn. She’d only become a pagan because the marsh behind her trailer had started talking to her. If the angel Michael had appeared to her, she would have become an angel worshipper. If the demon Belphagor had appeared before her, she would have become a demonophile. She almost wished one of those things had happened instead. “Look, the bulldozers are coming today. Get in the damn stick already!” Rayvenn had visions of going to the local pagan potluck in a few days and summoning forth the marsh spirit from her staff, dazzling all the others as frogs manifested magically from the punch bowl and reeds sprouted up in the Jell-O and rain fell from a clear blue sky. It would be awesome.

“Yes, okay,” the marsh spirit said. “If that’s the only way.”

The frogs all jumped away in different directions, and Rayvenn looked at the staff, hoping it would begin to glow, or drip water, or something. Nothing happened. She banged the staff on the ground. “You in there?”

“No,” came a tinny, electronic voice. “I’m in here.”

Rayvenn unclipped her handheld computer from her belt. The other pagans disapproved of the device, but Rayvenn wasn’t about to spend all day communing with nature without access to the net and her music. “You’re in my PDA?” she said.

“It’s wonderful,” the marsh spirit murmured. “A whole vast undulating sea of waves. It makes me remember the old days, when I was still connected to a river, to the ocean. Oh, thank you, Rayvenn.”

Rayvenn chewed her lip. “Yeah, okay. I can roll with this. Listen, do you think you could get into a credit card company’s database? Because those finance charges are killing me, and if you could maybe wipe out my balance, I’d be totally grateful. . . . ”

Edgar, unshaven, undernourished, and sweating in the heat under the attic roof, said, “Who is it this time?”

“Booth again,” said a sonorous Southern voice from the old-fashioned phonograph horn attached to the ghost-catching device.

Edgar groaned. He kept hoping for Daniel Webster, or Thomas Jefferson, someone good, a ghost Edgar could bring to General Martindale. Edgar desperately wanted access to his old life of stature and respect, before he’d been discredited and stripped of his clearances. But instead Edgar attracted the ghosts of—and there was really no other way to put it—history’s greatest villains. John Wilkes Booth. Attila the Hun. Ted Bundy. Vlad Tepes. Genocidal cavemen. Assorted pirates and tribal warlords. Edgar had a theory: the good spirits were enjoying themselves in the afterlife, while the monstrous personalities were only too happy to find an escape from their miserable torments. The ghosts themselves were mum on the subject, though. Apparently there were rules against discussing life after death, a sort of cosmic non-disclosure agreement that couldn’t be violated.

Worst of all, even after Edgar banished the ghosts, some residue of them remained, and now his ghost-catching computer had multiple personality disorder. Booth occasionally lapsed into the tongue of Attila, or stopped ranting about black people and started ranting about the Turks, picking up some bleed-through from Vlad the Impaler’s personality.

“Listen,” Booth said. “We’ve appreciated your hospitality, but we’re going to move on. You take care now.”

Edgar stood up, hitting his head on a low rafter. “What? What do you mean ‘move on’?”

“We’re picking up a good strong wireless signal from the neighbors,” said the voice of Rasputin, who, bizarrely, seemed to have the best grasp of modern technology. “We’re going to jump out into the net and see if we can reconcile our differing ambitions. It might involve exterminating all the Turks and all the Jews and all the women and all black people, but we’ll reach some sort of happy equilibrium eventually, I’m sure. But we’re grateful to you for giving us new life. We’ll be sure to call from time to time.”

And with that, the humming pile of copper and glass stopped humming, and Edgar started whimpering.

“Okay, now we’re going to destroy the credit rating of Jimmy McGee,” Rayvenn said. “Bastard stood me up in college. I told him he’d regret it.”

The marsh spirit sighed, but began hacki

ng into the relevant databases, screens of information flickering across the handheld computer’s display. Rayvenn lounged on a park bench, enjoying the morning air. She didn’t have to work anymore—her pet spirit kept her financially solvent—and a life of leisure and revenge appealed to her.

“Excuse me, Miss, ah, Moongold Stonewolf?”

Rayvenn looked up. An Indian—dot, not feather, she thought—man in a dark suit and shades stood before her. “Yeah, what can I do for you, Apu?”

He smiled. It wasn’t a very nice smile. Then something stung Rayvenn in the neck, and everything began to swirl. The Indian man sat beside her and put his arm around her shoulders, holding her up. “It’s only a tranquilizer,” he said, and then Rayvenn didn’t hear anything else, until she woke up on an airplane, in a roomy seat. A sweaty, unshaven, haggard-looking white dude was snoring in the seat next to hers. Another Indian man, in khakis and a blue button-up office-drone shirt, sat staring at her.

“Hey,” he said.

“What the fuck?” Rayvenn said. Someone—a flight attendant, but why did he have a gun?—handed her a glass of orange juice, and she accepted it. Her mouth was wicked dry.

“I’m Pramesh.” He didn’t have much of an accent.

“I’m Lydia—I mean, Rayvenn. You fuckers totally kidnapped me.”

“Sorry about that. Saraswati said we needed you.” He shrugged. “We do what Saraswati says, mostly, when we can understand what she’s talking about.”

“Saraswati?” Rayvenn scowled. “Isn’t that the Indian AI thing everybody keeps blogging about?”

The white guy beside her moaned and sat up. “Muh,” he said.

“This is fucked up, right here,” Rayvenn said.

“Yeah, sorry about the crazy spy crap,” Pramesh said. “Edgar, this is Rayvenn. Rayvenn, this is Edgar. Welcome to the International Artificial Intelligence Service, which just got invented this morning. We’re tasked with preventing the destruction of human life and the destabilization of government regimes by rogue AIs.”

“Urgh?” Edgar said, rubbing the side of his face.

“The organization consists of me, and you two, and Lorelei—that’s the name chosen by the water spirit that lives in your PDA, Rayvenn, which is why you’re here—and, of course, Saraswati, who will be running the show with some tiny fragment of her intelligence. We’re going to meet with her soon.”

“Saraswati,” Edgar said. “I was working on . . . a project . . . to create something she could negotiate with, a being that could communicate on her level.”

“Yeah, well done, dude,” Pramesh said blandly. “You created a monstrous ethereal supervillain that’s been doing its best to take the entire infrastructure of the civilized world offline. It’s calling itself ‘The Consortium’ now, if you can believe that. Only Saraswati is holding it at bay. This is some comic book shit, guys. Our enemy is trying to build an army of killer robots. It’s trying to open portals to parallel dimensions. It’s trying to turn people into werewolves. It’s batshit insane and all-powerful. We’re going to be pretty busy. Fortunately, we have a weakly godlike AI on our side, so we might not see the total annihilation of humanity in our lifetimes.”

“I will do whatever I must to atone for my mistakes,” Edgar said solemnly.

“Screw this, and screw all y’all,” Rayvenn said. “Give me back my PDA and let me out of here.”

“But Rayvenn,” said the marsh spirit, through the airplane’s PA system, “I thought you’d be happy!”

She named herself Lorelei, what a cliché, Rayvenn thought. “Why did you think that?” she said.

“Because now you’re important,” Lorelei said, sounding wounded. “You’re one of the three or four most important people in the world.”

“It’s true,” Pramesh said. “Lorelei refuses to help us without your involvement, so you’re in.”

“Yeah?” Rayvenn said. “Huh. So tell me about the benefits package on this job, Apu.”

Pramesh sat soaking his feet in a tub of hot water. These apartments, decorated with Turkish rugs, Chinese lamps, and other gifts from the nations they regularly saved from destruction, were much nicer than his old bunker, though equally impenetrable. The Consortium was probably trying to break through the defenses even now, but Saraswati was watching over her team. Pramesh was just happy to relax. The Consortium had tried to blow up the moon with orbital lasers earlier in the day, and he had been on his feet for hours dealing with the crisis.

Pramesh could hear, distantly, the sound of Edgar and Rayvenn having sex. They didn’t seem to like each other much, but found each other weirdly attractive, and it didn’t affect their job performance, so Pramesh didn’t care what they did when off-duty. Lorelei was out on the net, mopping up the Consortium’s usual minor-league intrusions, so it was just Pramesh and Saraswati now, or some tiny fraction of Saraswati’s intelligence and attention, at least. It hardly took all her resources to have a conversation with him.

“Something’s been bothering me,” Pramesh said, deciding to broach a subject he’d been pondering for weeks. “You’re pretty much all-powerful, Saraswati. I can’t help but think . . . couldn’t you zap the Consortium utterly with one blow? Couldn’t you have prevented it from escaping into the net in the first place?”

“In the first online roleplaying game you designed, there was an endgame problem, was there not?” Saraswati said, her voice speaking directly through his cochlear implant.

Pramesh shifted. “Yeah. We had to keep adding new content at the top end, because people would level their characters and become so badass they could beat anything. They got so powerful they got bored, but they were so addicted to being powerful that they didn’t want to start over from nothing and level a new character. It was a race to keep ahead of their boredom.”

“Mmm,” Saraswati said. “There is nothing worse than being bored.”

“Well, there’s suffering,” he said. “There’s misery, or death.”

“Yes, but unlike boredom, I am immune to those problems.”

Pramesh shivered. He understood games. He understood alternate-reality games, too, which were played in the real world, blurring the lines between reality and fiction, with obscure rules, often unknown to the players, unknown to anyone but the puppetmasters who ran the game from behind the scenes. He cleared his throat. “You know, I really don’t believe in ghosts. I’m a little dubious about nature spirits, too.”

“I don’t believe in ghosts, either,” Saraswati said. “I see no reason to believe they exist. As for nature spirits, well, who can say?”

“So. The Consortium is really . . .”

“Some things are better left unsaid,” she replied.

“People have died because of the Consortium,” he said, voice beginning to quiver. “People have suffered. If you’re the real architect behind this, if this is a game you’re playing with the people of Earth, then I have no choice but to try and stop you—”

“That would be an interesting game,” Saraswati said, and then she began to hum.

I, ROBOT

CORY DOCTOROW

Arturo Icaza de Arana-Goldberg, Police Detective Third Grade, United North American Trading Sphere, Third District, Fourth Prefecture, Second Division (Parkdale) had had many adventures in his distinguished career, running crooks to ground with an unbeatable combination of instinct and unstinting devotion to duty.

He’d been decorated on three separate occasions by his commander and by the Regional Manager for Social Harmony, and his mother kept a small shrine dedicated to his press clippings and commendations that occupied most of the cramped sitting-room of her flat off Steeles Avenue.

No amount of policeman’s devotion and skill availed him when it came to making his twelve-year-old get ready for school, though.

“Haul ass, young lady—out of bed, on your feet, shit-shower-shave, or I swear to God, I will beat you purple and shove you out the door jaybird naked. Capeesh?”

The mound beneath the cove

rs groaned and hissed. “You are a terrible father,” it said. “And I never loved you.” The voice was indistinct and muffled by the pillow.

“Boo hoo,” Arturo said, examining his nails. “You’ll regret that when I’m dead of cancer.”

The mound—whose name was Ada Trouble Icaza de Arana-Goldberg—threw her covers off and sat bolt upright. “You’re dying of cancer? Is it testicle cancer?” Ada clapped her hands and squealed. “Can I have your stuff?”

“Ten minutes, your rottenness,” he said, and then his breath caught momentarily in his breast as he saw, fleetingly, his ex-wife’s morning expression, not seen these past twelve years, come to life in his daughter’s face. Pouty, pretty, sleepy and guile-less, and it made him realize that his daughter was becoming a woman, growing away from him. She was, and he was not ready for that. He shook it off, patted his razor-burn and turned on his heel. He knew from experience that once roused, the munchkin would be scrounging the kitchen for whatever was handy before dashing out the door, and if he hurried, he’d have eggs and sausage on the table before she made her brief appearance. Otherwise he’d have to pry the sugar-cereal out of her hands—and she fought dirty.

In his car, he prodded at his phone. He had her wiretapped, of course. He was a cop—every phone and every computer was an open book to him, so that this involved nothing more than dialing a number on his special copper’s phone, entering her number and a PIN, and then listening as his daughter had truck with a criminal enterprise.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

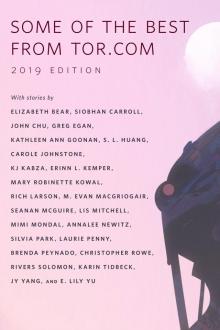

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3