- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

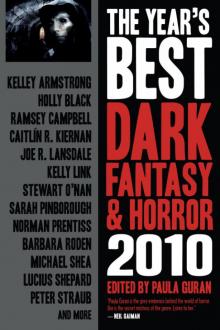

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Page 7

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Read online

Page 7

Andre stared some moments at his reflection, then turned to Ricky. “Now I tell you what it is . . . you say your name was Rocky?”

“Ricky.”

“Ricky, now Ima tell you what it is. I came to see, and be seen by Him. When He really sees you, you can see through His eyes, and you can live His mind.”

“But what if I don’t want to live his mind?”

“You can’t! You didn’t pay the toll! You’ll see some shit though! You’ll see enough, you’ll know that if you got any adventure in your soul, you got to pay that toll! But that’s up to you! Now look, an learn!”

He faced the mirror again, and in a cracked voice he cried, “Ia! Ia! Ia fthagn!”

And the mirror, ever so slightly, contracted, and the faintest circumference of white showed round its great rim, and encompassing that ring of pallor, something black and scaly like a sea-beast’s hide crinkled into view . . . and Ricky realized that they stood before the pupil of an immense eye.

And Ricky found his feet were rooted, and he could not turn to flee.

And he beheld a dizzying mosaic of lights flashing to life within the mighty pupil. A grand midnight vision crystallized: the whole San Francisco Bay lay within the black orb, bordered by the whole bright oroboros of coastal lights . . .

He and Andre gazed on the vista, on the Bridges’ glittering spines transecting it, all their lengths corpuscled with fleeing lights red and white. The two men gazed on the panorama and it drank their minds. Rooted, they inhabited its grandeur, even as it began a subtle distortion. The vista seemed tugged awry, torqued towards the very center of the giant’s pupil. And within that grand, slow distortion, Ricky saw strange movements. Across the Bay Bridge, near its eastern end, the cargo cranes of West Oakland—tracked monsters, each on four mighty legs—raised and bowed their cabled booms in a dinosaurian salute—obeisance, or acclaim . . . While to their left, the giant tanks on Benecia’s tarry hills, and the Richmond tanks too in the West, began a ponderous rotation on their bases, a slow spin like planets obeying the pupil’s gathering vortex.

Andre cried out, to Ricky, or just to the world he was about to leave, “I see it all coming apart! In detail! Behold!”

This last word reverberated in a brazen basso far larger than the lean man’s lungs could shape. And the knell of that voice awoke winds in the night, and the winds buffeted Ricky as though he hung in the night sky within the eye, and Ricky knew. He knew this being into whose view he’d come! Knew this monster was the King of a vast migration of titans across the eons of the countless Space-Times! Over the gale-swept universe they moved, these Great Old Ones. Across the cracked continents they trawled, they plundered! Worlds were the pastures that they grazed, and the broken bodies of whole races were the pavement that they trod!

It astonished him, the threshold to which this Andre, night-walking zealot, had brought him. He looked at Andre now, saw the man utterly alone at the brink of his apotheosis. How high he seemed to hang in the night winds! Look at the frailty of that skinny frame! The mad greed of his adventure!

Andre seemed to shudder, to gather himself. He looked back at Ricky. He looked like he was seeing in Ricky some foreigner in a far, quaint land, some backward Innocent, unknowing of the very world he stood in.

“On squid, man,” he said, “ . . . on squid, Ricky, you get big! All hell breaks loose in the back of your brain, and you can hold it, you can contain it! And then you get to watch Him feed. And now you’ll see. Just a little! Not too much! But you going to know.”

Andre turned, and faced the eye. He gathered himself, gathered his voice for a great shout:

“Here’s my witness! Here I come!”

And he vaulted from the balcony, out into the pupil—impacted it for an instant, seemed to freeze in mid-leap as if he had struck glass—but in the instant after, was within the vast inverted cone of light-starred night, and hung high, tiny but distinct, above the slowly twisting panorama of the great black Bay all shoaled and shored and spanned with light. That galactic metropolis, round its core of abyss, was—less slowly now—still contorting, twisting toward the center of the pupil . . .

And Ricky found that he too hung within it, he stood on the wide cold air in the night sky, he felt against his face the winds’ slow torque towards the the center of the Old One’s sight.

And now all Hell, with relentless slow acceleration, broke loose. The City’s blazing architected crown began to discohere, brick fleeing brick in perfect pattern, in widening pattern, till they all became pointillist buildings snatched away in the whirlwind, and from the buildings, all the people too like flung seed swirled up into the night, their evaporating arms raised as in horror, or salute, crying out their being from clouding faces that the black winds sucked to tatters . . .

He saw the great bridges braided with—and crumpling within—barnacle-crusted tentacles as thick as freeway tunnels, saw the freeways themselves—pillared rivers of light—unravelling, their traffic like red and white stars fleeing into the air, into the cyclone of the Great Old One’s attention.

And an inward vision was given to Ricky, simultaneous with this meteoric overview. For he also knew the Why of it. He knew the hunger of the nomad titans, their unappeasable will to consume each bright busy outpost they could find in the universal Black and Cold. Knew that many another world had fled, as this one fled, draining into the maw of the grim cold giants, each world’s collapsing roofs and walls bleeding a smoke of souls, all sucked like spume into the mossy curvature of His colossal jaws . . .

It was perfectly dark. It was almost silent, except for a rattle of leaves. The cold against his face had the wet bite of fog . . .

Ricky shook his head, and the dark grew imperfect. He put out his hand and touched rough wooden siding. He was alone on the porch, no lantern now, no armchair, no one else. Just dead leaves in crackly little drifts on the floorboards as—slowly and unsteadily—he started across them.

He had seen some shit. Stone cold sober, he had seen. And now the question was, who was he?

He crossed the leaf-starred grass, on legs that felt increasingly familiar. Yes . . . here was this Ricky-body that he knew, light and quick. And here was his Mustang, blown oak leaves chittering across its polished hood. And still the question was, who was he?

He was this car, for one thing, had worked long to buy it and then to perfect it. He got behind the wheel and fired it up, felt his perfect fit in this machine. Flawlessly it answered to his touch, and the blue beast purred up through the leaf-tunnel as the house—a doorless, glassless derelict—fell away behind him. But this Ricky Deuce . . . who was he now?

He emerged from the foliage, and dove down the winding highway. There was the fog-banked Bay below, the jewelled snake of the Hood glinting within its gray wet shroud, and Ricky took the curves just like his old self, riding one of the hills’ great tentacles down, down towards the sea they rooted in . . .

There was something Ricky had to do. Because in spite of his body, his nerves being his, he didn’t know who he was now, had just had a big chunk torn out of him. And there was something terrible he had to do, to locate, by desperate means, the man he had lost, to find at least a piece of him he was sure of.

His hands and arms knew the way, it seemed. Diving down into the thicker fog, he smoothly threw the turns required . . . and slid up to the curb before the liquor store they’d parked near . . . when? A universe ago. Parked and jumped out.

Ricky was terrified of what he was going to do, and so he moved swiftly to have it done with, just nodding to his recent companions as he hastened into the store—nodding to the Maoris in shades, to the guys with the switchblade cap-bills, to the guys with the crimson hoods and the golden pockets. But rushed though he was, it struck him that they were all looking at him with a kind of fascination . . .

At the counter he said, “Fifth of Jack.” He didn’t even look to see what he peeled off his wad to pay for it, but there were a lot of twenties in his change. The Arab b

agged him his bottle, his eyes fixed almost raptly on Ricky’s, so Ricky was moved to ask in simple curiosity, “Do I look strange?”

“No,” the man said, and then said something else, but Ricky had already turned, in haste to get outside where he could take a hit. Had the man said no, not yet?

Ricky got outside, cracked the cap, and hammered back a stiff, two-gurgle jolt.

He scarcely could wait to let it roll down and impact him. He felt the hot collision in his body’s center, the roil of potential energy glowing there, then poked down a long, three-gurgle chaser. Stood reeling inwardly, and outwardly showing some impact as well . . .

And there it was: a heat, a turmoil, a slight numbing. No more. No magic. No rising trumpets. No wheels of light . . . The half-pint of Jack he’d just downed had no marvel to show like the one he’d just seen.

And so Ricky knew that he was someone else now, someone he had not yet fully met.

“ ’Sup?” It was the immense guy in the lavender sweats. He had a solemn Toltec-statue face, but an incongruously merry little smile.

“ ’S happnin,” said Ricky. “Hey. You want this?”

“That Jack?”

“Take the rest. Keep it. Here’s the cap.”

“No thanks.” This to the cap. The man drank. As he chugged, he slanted Ricky an eye with something knowing, something I thought so in it. Ricky just stood watching him. He had no idea at all of what would come next in his life, and for the moment, this bibulous giant was as interesting a thing as any to stand watching . . .

The man smacked his lips. “It ain’t the same, is it?” he grinned at Ricky, gesturing the bottle. “It just don’t matter any more. I mean, so I understand. I like the glow jus fine myself. But you . . . see, you widdat Andre. You’ve been a witness.”

“Yeah. I have. So . . . tell me what that means.”

“You the one could tell me. AIs I know is I’d never do it, and a whole lotta folks around here they’d never do it—but you didn’t know that, did you?”

“So tell me what it means.”

“It means what you make of it! And speakin of which, man, of what you might make of it, I wanna show you something right now. May I?”

“Sure. Show me.”

“Let’s step round here to the side of the building . . . just round here . . . ” Now they stood in the shadowy weed-tufted parking lot, where others lounged, but moved away when they appeared.

“I’m gonna show you somethin,” said the man, drawing out his wallet, and opening it.

But opening it for himself at first, for he brought it close to his face as he looked in, and a pleased, proprietary glow seemed to beam from his Olmec features. For a moment, he gloated over the contents of his billfold.

Then he extended and spread the wallet open before Ricky. There was a fat sheaf of bills in it, hand-worn bills with a skinlike crinkle. It seemed the money, here and there, was stained.

Reverently, Olmec said, “I bought this from the guy that capped the guy it came from. This is as pure as it gets. Blood money with the blood right on it! An you can have a bill of it for five hundred dollars! I know that Andre put way more than that in your hand. I know you know what a great deal this is!”

Ricky . . . had to smile. He saw an opportunity at least to gauge how dangerously he’d erred. “Look here,” he told Olmec. “Suppose I did buy blood money. I’d still need a witness. So what about that man? Will you be my witness for . . . almost five grand?”

Olmec did let the sum hang in the air for a moment or two, but then said, quite decisive, “Not for twice that.”

“So Andre got me cheap?”

“Just by my book. You could buy witnesses round here for half that!”

“I guess I need to think it over.”

“You know where I hang. Thanks for the drink.”

And Ricky stood there for the longest time, thinking it over . . .

About the Author

Michael Shea learned to love the “genres” from the great Jack Vance’s Eyes of the Overworld, chance-discovered in a flophouse in Juneau when Shea was twenty-one. He tilled the field of sword-and-sorcery for more than a decade (Quest for Simbilis, In Yana the Touch of Undyine, Nifft the Lean). Concurrently he wallowed in the delights of supernatural/extraterrestrial horror, primarily in the novella form, and this remains his genre of choice (as can be seen in the collections Polyphemus and The Autopsy and Other Tales). In the last decade or so he has added hommages to H.P. Lovecraft to his novella work (as in collection Copping Squid.) Currently he is writing a trilogy of near-future thrillers: The Extra, Assault on Sunrise, and Fortress Hollywood.

Story Notes

This particular tale was written for S.T. Joshi’s Black Wings: New Tales of Lovecraftian Horror, an anthology that wasn’t published until 2010. Luckily (for us) Shea included it as the title story of his most recent collection which was published in 2009. As for the San Francisco setting: If there were anywhere one might cop squid, it would be there.

MONSTERS

STEWART O’NAN

They were going to be monsters, for the church—Creatures from the Black Lagoon. Mark wanted to be Dracula, but Father Don said only one person could, and Derek convinced him it would be more fun. You got to wear a suit with a zipper up the back and a head that fit like a diving helmet. They could scare the little kids and gross out the girls. No one would know who they were.

“Plus it’s boring by yourself,” Derek said. “You just sit there.”

“You don’t need fangs,” Derek said. “There’s already teeth in the head.”

It was Mark’s only argument. It was like that with Derek, he was always in charge, which was all right, because Mark was shy and terribly aware and ashamed of it. Plus Derek never ditched him like Peter did. Peter was his brother; he was only two years older than Mark. They’d always played together, ever since they were little, but since Peter started at the high school this fall, he was never home after school. At dinner when Mark brought it up, his father just sighed. “Why don’t you go next door?” he said. “You and Derek should be able to find something to do.”

That’s what they were doing, just messing around. It was a Thursday after school and there was nothing to do, so Derek brought out his Daisy and they took turns plinking the same six pop bottles off some old railroad ties Derek’s stepfather had piled in the back lot. The gun was so weak they didn’t even fall over sometimes, just tinked and wobbled.

It was Derek’s idea to play Shooting Gallery. One of them hid behind the ties and then popped up and you had to shoot him. You only pumped the gun once, and they had their jackets on; it only stung if it hit bare skin. You crawled around behind the ties and then popped up and the other person tried to shoot you.

They did that for ten minutes but it was boring. Then Mark came up with Moving Target. In this one, you jumped up and ran and then dove behind the ties. This was even more boring because no one got shot.

Then Derek made up Ambush. The guy with the gun hid somewhere behind the piles of woodchips and gravel, and the guy who popped up threw hand grenades—just round stones Derek’s stepfather used to edge the little goldfish ponds he built.

Mark had the gun. He pumped it once and crouched behind a sharp pallet of bricks, waiting for Derek to lob one of the stones. They were a little smaller than baseballs, and he didn’t want to get hit with one. He peeked around the corner and saw Derek start to pop up and toss the grenade like a soldier, like a hook shot—saw the stone leave his hand and arc towards him.

He’d have time to think about this later: how impossible it all was. He saw the stone was going to miss, so he ducked around the corner, firing without even bringing the gun up. From the hip, just like in the movies.

He expected Derek to run but he was watching the grenade like it might really explode.

It was just one shot, from the hip.

Derek grabbed his face and bent over, holding it.

Mark thought he was faking. He loved dea

th scenes on TV, dropping to the carpet in their rec room, one hand clutching his heart as he gasped out his last words, the other reaching for Mark’s sneaker. But then he was screaming—high and loud and over and over—and walking fast toward his backdoor, his hand still there, as if he were trying to keep the eye in.

Mark dropped the gun and ran over and walked along with him. “Are you okay?”

“No.”

“Let me see.”

“No.” He was walking slower now, and Mark could have stopped him, but there was blood coming out between his fingers and Mark couldn’t think. He went up the porch stairs in front of him and opened the storm door. He saw his own hands were empty, and thought: I shouldn’t leave the gun out there.

“Sarah!” he called inside, because Derek’s sister was the only one home. He went through the kitchen into the front hall and called her, and she came running down, asking what had happened. When she saw the blood she grabbed Derek and hauled him to the sink and started running water. Mark had a crush on her—her lip gloss, her purple scrunchy, the way she bowed down and then reared up and flung her hair over her head—and her taking charge made her seem heroic, older, even more unreachable.

“What happened?” she asked.

“It was my fault,” Mark said. “We were playing with the gun—”

“God damn it,” she said. “I can’t believe it, you’re so stupid, both of you.”

Sarah ran some water on a dishcloth and got right up next to Derek. She told him it was okay, everything was okay. They needed to see how bad it was. Derek wasn’t screaming anymore, it was more like crying, trying to breathe in too fast. She had her arm over his shoulders, her face so close they could have been kissing. “Yeah, I know,” she said, “it’s all right, we just need to see.”

He nodded and Sarah took his hand away from his eye.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

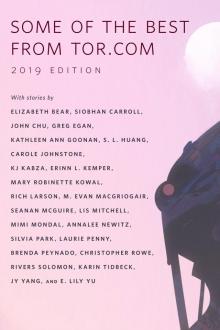

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3