- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Hammered jc-1 Page 9

Hammered jc-1 Read online

Page 9

“I’d like that. Pull up a chair.” He set the manuals on the edge of his desk, away from the interface plate, and gestured to the one he’d cleared. The skin of his hands showed faint irregularities of color, speaking to Elspeth of old deep burns or something else requiring skin grafts.

She shook her head. “How about I buy you dinner?”

He checked the time in the corner of the flat monitor pane canted at an angle like a reading stand over the top of his desk. Elspeth found it interesting that he preferred the pane to contacts or a holographic interface. Still, she imagined he spent a lot of time staring at it. “How did it get so late? Sure, let me grab my jacket. My roommates are at a friend’s place for dinner.” He wiggled his fingers in the air to indicate quotation marks.

I wonder what quote roommates unquote are. She stepped back as he walked around the desk, rolling down his shirtsleeves and buttoning the cuffs before he brushed past her to take his coat down off the peg beside the door. “What do you want?”

“Anything’s good,” she answered, wondering if he meant — or caught — the double entendre. “I wonder if that little noodle shop on the corner by the university is still there.”

He took the knob in his hand and held the door open for her. He passed his thumbprint over the sensor as well as turning the key in the lock. “When was the last time you were there?”

She almost laughed in realization. “About thirteen years.”

“Ah.”

Elspeth could see evening light through the double glass doors at the end of the corridor as they walked. She knew he was waiting for an explanation. “I’ve been out of Toronto for a while. I’ll tell you about it if I get a couple of beers in me.”

“You do that,” he said, as the outside doors whisked open before them, enfolding them in warm autumn air like a humid exhalation.

An hour later at a restaurant still called “Lemon Grass,” Elspeth picked up her chopsticks and leaned forward over the steaming bowl of noodles, closing her eyes to inhale. “Jesus, that smells good.”

Across the table, Gabe tilted his bowl toward his mouth. Slurping noodles, he nodded. He chewed, swallowed, and cleared his throat. “I love this stuff. So tell me about your project. Our project. Do you want another beer?”

“Please. Well, here’s the thing. I don’t know how much you remember from about thirteen years back… Do you recall anything what the media said then? About my work in particular?”

Gabe signaled the waitress. He had a knack, Elspeth noticed, for catching people’s eye. “I saw you on Network Tonite. The night Alex Ugate was shot.”

“Oh.” Elspeth set her chopsticks aside. “That was a bad business.” She picked the Sapporo up before the waitress’s hand had really left it and took a swallow. Two should be my limit. You’re cut off after this one, Elspeth. “That was about the worst night of my life.”

“I imagine. I’ve had a few of those myself.” He set his bowl down and laid the chopsticks on the blue porcelain rest, reaching for the teapot. The bowls and teacups were still as mismatched as she remembered: Gabe’s cup was red and blue, and Elspeth’s was white with translucent rice grains throughout. “I remember they showed the VR feed, and you talking with some dead engineer…”

She chuckled, distracted enough to pick her chopsticks back up, fingertips fretting the splintery wood. “Nikola Tesla. He wasn’t a true AI, though — just a construct personality. A responder designed to mimic a long-dead man.”

Gabe nodded. “And then a riot broke out in the TV studio, as I recall.” As if realizing what he had said, he continued quickly. “Do you still think you were on the right track?”

After a long pause, she forced herself to keep chewing. “Gabe, I’m sure of it. It’s just a matter of creating the right construct personality. After a certain point, I believe they’ll self-generate. Given sufficient system resources, that is.”

“Ah.” He seemed pensive.

She reached out and tapped his hand. “Speak.”

His shoulder rose and fell under light-blue broadcloth. “I’m wondering if the research would still be as controversial now. Ten years later.” She didn’t answer immediately, and after a sip of beer he continued. “Course, I never much understood what the fuss was then.”

“It won’t be controversial,” she whispered, “because no one will know that we’re doing it this time.” She nibbled on the edge of her thumbnail. “And as for what the fuss was — well, what was the fuss over nanotech, or bioengineering, or cloning? People used to get shot for performing abortions, for Christ’s sake. Fundamentalists are nuts.” Self-consciously, she touched her gold cross, watching fish circle in the tank on the wall.

“In the U.S., the only reason people don’t still get shot for performing abortions is because they’re not legal anymore,” Gabe replied. He picked up his chopsticks and sucked up another mouthful of noodles. “How on earth did you wind up going to jail for sedition, of all things?”

“It wasn’t sedition.”

“I remember the trial. Military Powers Act. Something else? Not espionage, or they wouldn’t have you on this project.”

Elspeth smoothed the palm of her hand over the speckled linoleum tabletop. Dark red vinyl crinkled under her thighs as she shifted position in the booth. “There is that.” She poured herself tea so she wouldn’t finish her beer too quickly.

Gabe watched quietly while she fidgeted.

“It was — noncooperation, I suppose you’d call it. Valens wanted someone — I mean, something — I wasn’t prepared to give him.” She changed the subject none too smoothly. “Where did you learn programming?”

“Now that is a long and ugly story. I used to play around for fun when I was a kid. There’s not much to do in the winters up north. We played a lot of Monopoly.”

Elspeth glanced up at him, surprised. Her eyes met his bay-blue ones, which twinkled amid sunbaked creases. Is he kidding? Yes. And no. “And you kept it up in the army?”

He shrugged and took a pull of his beer. “Not really. I was special forces. I got shot at.” The eyes looked down, and the twinkle left them. “Then I got out, got married, and had to get a real job. Which reminds me — I think we’ve got an unusually persistent somebody poking around the edges of the intranet. He hasn’t made it in, but he’s giving me a run for my money.”

“I’m keeping all my project work on the isolated intranet. Are you?”

“Yes. Although I can’t help but feel a bigger system might provoke things. Kind of a neurons-and-synapses kind of deal, n’est ce pas?” He trailed off, poking at his food. “How did you get into this line of work?”

“I started with an MSW and decided I was sick of watching inner city kids get chewed up by the system, so I went back to school for medicine and figured out I was too scared of hurting people to be a physician. That led me into psychiatry until I figured out I could hurt them worse. Thus,” she spread her hands wide, as if releasing a dove, “research.”

He raised his Sapporo and tapped it against hers. “Here’s to winding up someplace other than where you intended.”

“I already did that, Gabe.” The words came out too easily, revealing more than she had meant to.

“Yeah.” He finished the beer and set the bottle aside for the alert waitress to carry off.

In a moment, she was back with two more. Elspeth eyed hers uncertainly. “I should stop with these.”

“Do you have somewhere to be?”

She chewed, swallowed, regretting already the need to leave the warm, ginger-scented restaurant and go back to the hospital, to the reek of antiseptic and death. “Well… yeah.”

“Hell,” he said. “Drink the beer. I’ll walk you over. It is walkable?”

“Subway,” she replied, and he nodded.

“Close enough.”

1530 hours, Friday 8 September, 2062

Sigourney Street

Abandoned North End

Hartford, Connecticut

“Jenny,

it’s Gabe. Hope everything’s okay — sorry I missed you. I was just calling to let you know I’ve moved back to Toronto and give you my new contact information, but I guess I’ll e-mail it to you instead. Yes, as you’re guessing, that means I finally found work. It’s a good job, too, but I have to warn you about the shocker — I’m working with your old ‘friend’ Captain Valens. Except he’s Colonel Valens now, but anyway, I figured I should warn you before you heard it through the grapevine.

“I hope you’re out having a hot date on a Friday night, or at least down at that dive you call a corner pub watching the game. My money’s on Chelsea. Call me. Bye!”

I step away from the one-tenth-scale holographic projection of the head of Gabriel Castaign, formerly holding the rank of captain in the Canadian Army. Razorface watches over my shoulder. Boris stands on the fender of the Cadillac, and Face scratches him under the chin. The old tomcat rocks his head from side to side, leaning into the caress. “Jenny?”

“Don’t push your luck, Dwayne.”

He curls a corner of his lip at me in a close-mouthed smile. I’m probably the only person other than his momma who knows that name anymore. “Mexican standoff,” he says. “That your only message? You nearly ready to roll?”

“Yeah,” I say, downloading the information Gabe e-mailed me into my HCD. The H stands for holistic, but through the magic of linguistics, everybody calls it a “hip.” Whatever.

Valens? Fucking A, Gabe, you’d better have a hell of a good reason for that. He does, though. And it’s hard to be angry, because I know perfectly well what his reasons are.

His wife’s name had been Geniveve, and the irony of that still scalded me if I thought about it too hard. He’d married her after we were both out of the army, and their daughters were born late — the younger one only a year or so before Geniveve died. Long after he’d forgotten that he saved my life that time. I never forgot, even if I never got around to mentioning it to him. Like I never got around to mentioning some other things he didn’t need to know. We can put bases on Mars and miners on Ceres, but we can’t cure common heartbreak.

I stop playing with my HCD, thumb it off, and refill Boris’s automatic cat feeder and water fountain. He’s got a cat door keyed to a microchip. Face watches me, not quite letting me see him smile. Yeah, dammit, I take in strays. When I’m done, I grab my jacket and an overnight bag and lead Face over to the only-just-antique Bradford Tempest pickup in the left-hand bay.

I figure I’ll answer Gabriel’s call when I get home and have a little time to talk. And when I’ve cooled off a little, to be honest.

The Bradford isn’t much to look at, but it runs. The solid rubber tires and boulder-climbing suspension aren’t easy on the kidneys as we bushwhack our way to the highway, but thirty minutes later we’re southbound on I-91, passing the exit sign that reads “Dinosaur State Park Veteran’s Home and Hospital” and accelerating steadily toward New York City.p>

Because, baby, it’s Friday night.

We ride in silence, down highways older than my grandmother, through the acid-rain-etched hills and the centers of commerce of southern Connecticut. The highway unwinds before us, the sun gliding down the sky. Our first sight of the city is burn-scarred gray concrete towers flanking the highway — deserted now and unmaintained.

It’s still only early evening — three hours transit, more or less, and then another half hour looking for a spot before I pay too much to park the brave old truck in a guarded lot. I disarm the security system so Face can climb out the passenger side. I’ve got my gun unholstered and am leaning across to open the glove box when he stops, turns back, and slides his own piece out of the shoulder holster. He weighs it in his hand, standing close enough so the door blocks him from casual sight.

“Leave it,” I say.

He looks like he wants to chew his lip. I admire his restraint. “New York,” he says.

“Not the place to carry a gun.” New York City has a shoot-on-sight law, and the cops here aren’t content to let the neighborhoods run themselves. Never mind the martial law that’s gone into effect since the dikes went up between the City and the cold, rising Atlantic. That spot between my shoulderblades starts to itch as soon as I get within smelling distance of the place. I meet his eyes and frown. “Glove box, Face.”

He takes a breath to argue, so I let my expression slide toward Sergeant and he lets it out again and puts the gun in the box like a good boy, only slamming the door a little. I meet him by the front bumper. “So, do you have any idea where to go?”

He’s already walking, and I set the alarm and the flame-throwers before I follow.

He nods, but doesn’t say anything. The narrow street is dark and smells of garbage and the salt-sewage tang of the sea. I hurry to catch up, matching strides with him as he reaches the sidewalk. His shoulders are squared hard, and as I fall in on his right side I lay my metal hand on his elbow. “Talk to me.”

He turns his head away and spits. “Nothing to talk about. Will you stop fussing at me? You been acting like my grandmother all day. We just going to see a guy.”

I’m annoyed with myself, because he’s right; I have been clingy. It has something to do with the dark-haired woman who knows my name, though, and I’m not going into that right now. What sort of a guy? I would ask, but my head whirls as if I had spun in place for too long. I gasp and steady myself, one hand on a tenement wall in wet brick. Not good, Casey. Not good at all. I can almost feel the eyes of the predators marking me as my hand comes off Face’s arm. He checks himself midstride and turns back, irritation blending into concern.

Blurring, and the smell of dead people in the sun. Sound of rotors as I bring the chopper in low, a steaming clearing among strangler fig and vines. The door gunner swear-ing, and—

No.

I get it under control and stand up, leaning on the wall more than I want to. “S’all right, Face.” He doesn’t believe me, and I wave him off, striding forward again. I try not to let him see me clenching my jaw. “Just old bones and the drive.”

It isn’t, though. I know what it is — it’s feedback from my neural taps, and flashbacks, and I haven’t had one that bad in twenty years.

Ignoring Face’s anxiety, I move down the street toward wherever he’s leading me.

Avatar Gamespace

Phobos Starport

Circa A.D. 3400 (Virtual Clock)

Interaction logged Friday 8 September, 2062, 1900 hours

Leah gulped, leaning against the triple-thick crystal plates of the reception lounge view port, her booted feet firmly magnetized to the floor. If her VR were better, she would have been able to feel the space-chill seeping through them. She focused beyond the blinking sponsor-ship logos hanging in the glass just at eye level (AppleSoft, Venus Consolidated Erotic Industries, Unitek, Miller Genuine Draft, Amalgamated Everything) and let a long cool comforting draft of air flow into her mouth. “My God,” she whispered.

The starship hanging in the tiny moon’s shadow was visible as nothing so much as a silhouette and a more-regular pattern of lights against the stars. Leah reached up and tapped the crystal where the great ship’s lights were, calling up an outline display and then a schematic. She shook her head. Not quite. And tapped once more.

As if light had poured around the rim of the moon, The Indefatigable shone in virtual sunlight, the dull silver of her great wheel-on-a-spear shape catching highlights that never were. That wheel rotated slowly around the shaft, a spindly looking construction to connect the habitation ring to the incredibly deadly bulbs of the engines at the far end, some kilometers away.

It looked like a Christmas tree ornament, a bauble she could reach out and pluck with her hand. Leah knew it was longer than the Channel Bridge.

“You are gonna be mine,” she whispered, and broke into a radiant grin.

BOOK TWO

Of course, many people claim not to be convinced by this so-called climate change evidence. That is because they are shortsighted sociopathic mor

ons who don't want to lose any money.

- Bruce Sterling

1998

0600 hours, Saturday 9 September, 2062

New York City, New York

Somewhere on the East End

At the top of a flight of cement stairs with a rotten railing, I step through a narrow, mottled greenish door and into gray light. Moist shags of paint hang from it like bark from a sycamore, freckling my fingers as I hold it open for Razorface, a few steps behind me. The early morning is already sweat-hot and dank; suddenly, I realize how long we’ve been chasing a cold trail. I need a drink. After eight hours following Razorface through the gentle streets of New York City by night, I need several drinks. And maybe a cigarette — one I could smoke quickly, before I remember that I don’t smoke anymore.

He’s stopped behind me, just inside the doorway, sharing a parting handshake with the weedy young man we roused out of bed. I hadn’t realized the sheer number of people that my old friend has done favors for, which tells me I need to pay more attention. Missing things like that can get you dead.

None of the favor-owers know a damned thing about a dealer, a box full of Hammers, or anybody going on a road trip to Hartford. Face’s hunch was wrong.

The shit didn’t come out of New York, which is a relief and a puzzlement both.

“Face.”

He bangs fists with his boy one more time and turns back to me as the skinny kid steps away, into darkness. “Yah, Maker.”

“Food.” I feel wobbly, and I’m hoping it’s low blood sugar and a lack of caffeine instead of other problems. That can’t-get-warm feeling is starting to creep up my neck, my right fingers itching with the desire for a weapon. There hasn’t been a reason to reach for one, but we’ve been in and out of threat situations — narrow hallways, strangers’ living rooms, tenement housing, and alleyways — all night. Also, I keep seeing people I know are dead out of the corner of my good eye, which is never a good sign.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

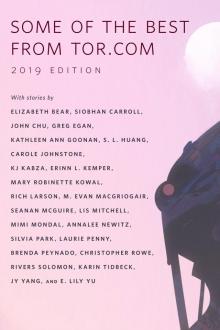

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3