- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Page 9

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 Read online

Page 9

“I thought Mark did a nice job too,” his mom said.

“I heard. Good projection.”

In the back seat, Peter made a face, and Mark elbowed him, and Peter went to hit him but stopped short just to make him flinch.

Outside the fields went by, long harvested, the stubble white and bent down by the reaper. He could smell someone burning leaves; you weren’t supposed to but people still did.

Nothing had changed, Mark thought. Nothing had happened. He’d just said his name, that was all.

But what if saying his name saved his eye? That was possible, wasn’t it? That’s what faith was. If the two farmers had had faith—was that the meaning of it? He wanted to ask his dad: What were the farmers supposed to do?

It was dumb thinking about it; it was just made-up.

At home they changed clothes and ate lunch and put on the Steeler game. It was dumb; they were beating up on Houston. Mark was thinking about going out and raking the yard when Derek’s stepfather came over.

Mark answered the door. Usually he’d just let him in, but Derek’s stepfather asked if his dad was around.

“I’ll go get him,” Mark said.

His dad was lying on the couch with the football in his lap. He looked surprised and got up and handed off to Peter, and Mark knew not to follow him.

His dad didn’t come right back. He closed the door and went upstairs where his mom was working on the costumes, and then in a while the two of them came down together. Peter looked at Mark like this was about him.

His dad clicked the set off and had everyone sit down.

“Take hands,” he said, and they did.

“Mrs. Rota just called. The doctors said Derek’s eye was just too badly damaged.”

He went on, but Mark had stopped listening, concentrating on the shot, that one stupid moment with the gun. It was Derek who made up the game, it was Derek’s rifle. Derek had shot at him a million times, even shooting one of his mom’s cigarettes out of his mouth on three tries. But none of that mattered. Now, bending his head in prayer again, his dad’s hand strong in his, all that mattered was that one shot. It was his fault, and he was sorry, but that wasn’t enough.

“Amen,” his dad said, and there was the squeeze, like a reminder.

Later he went out and raked the yard by himself until he saw his mom at her sewing room window looking down at him. She’d bought a huge trash bag that looked like a pumpkin, and he stuffed it with leaves and faced it toward the road so you could see it when you came around the curve. Then he went in and watched the late game, or sat there not watching, startled when Peter called out, “Nice! Nice!”

No one told him it wasn’t his fault. After the dishes, his mom took him into the living room and said he hadn’t meant for this to happen. Tucking him in, his dad told him he shouldn’t blame himself, that what was done was done. He was a good guy, everyone knew that. Derek knew that, Derek’s parents knew it. Okay?

“Okay,” Mark said.

His door closed, blocking out the hall light, leaving him alone. He wondered if Derek was awake in the hospital, if he’d gotten a new roommate. He closed both his eyes and tried to see. Blue dots floated, then shifted when he tried to look at them, drifted like galaxies, little soft stars. He opened his eyes and the room grew back. No, he thought, that wasn’t what it was like at all.

It was just one, he still had the other. Peter said that to be mean, but it was true too.

The wind was in the trees. It was only two weeks till Halloween; his mom had already bought candy and hid it where his dad couldn’t get at it, set out bowls of candy corn around the house. Would Derek be able to be a Creature? Mark wanted to see him, to say he was sorry to his face. He couldn’t remember if he did when he shot him. It was funny: he thought he would never forget it, but already, like his part in the service this morning, the Steeler game, the leaves, the two farmers—like the blue stars under his eyelids, it was all fading away.

The next day his mom picked him up after school and drove him over to church. Father Don had the two suits hung over folding chairs in the parish hall. They were greenish-black, the color of snakes, and sagged like empty skins. They were so fake it made Mark want to laugh. Their claws came to sharp points. On the table sat the two heads, the eyes bugged out under angry brows, flipperlike gills behind the jaw.

“You look out of the mouth,” Father Don explained, and fit it over his head.

“Can you see?” his mom asked.

He could, but just a wedge between two even rows of ridiculous fangs. He’d have to remember to tell Derek.

“Okay,” Father Don said, “take that off and let’s try the body.”

It was heavy, and the webbed hands went on separately, like rubber gloves. The feet went over his shoes, kept on with a gumband. It was like wearing armor, he thought, everything covered up.

“How does it feel?” Father Don asked him.

“Good,” Mark said.

They had him move around some; it wasn’t easy.

“Okay,” Father Don said, “get that off and try on the other one. They’re supposed to be the same size but it never hurts to check.”

So then Derek was going to do it. For some reason, it made Mark afraid the suit wouldn’t fit.

It did. Father Don zipped him up, and Mark put the head on and stumped around.

“Growl,” his mother said. “Look like you’re going to drag someone overboard and take them to your secret cave.”

“Graaaahhhh,” Mark tried, claws raised, and his mother screamed like she was the girl in the movie. Father Don stepped between them to protect her, and he knocked him aside with one blow.

“Very convincing,” Father Don said. “Okay, let’s get it off.”

Mark wondered if Dracula would have been better. Probably not. It all seemed cheesy now, dumb.

After that they visited Derek. He was awake, drinking ginger ale through a straw. He smiled when he saw Mark. He had a patch over the eye, otherwise he was fine. He turned so his good one was aimed at him. It was brown; Mark hadn’t noticed it before.

“Hey,” he said.

“Hey,” Mark said. “How’s it going?”

“All right. Got to miss school. It would have been great but they don’t have cable, just the regular stations.”

Mark didn’t have anything else to say.

“Randy took the gun apart,” Derek said. “Did you know that?”

“No.”

“He unscrewed all the parts and put them in this plastic bag. He says I can have it back when I’m fifteen.”

“Wow.”

“Yeah. That’s all right, he said we might get a Nintendo 64 for my birthday.”

“Cool,” Mark said. It was good to hear Derek talk like he always did. It was only bad when he looked at the patch. “Hey, I’m sorry.”

“That’s okay,” Derek said. “Did you know there’s a club for people with one eye? Yeah, it’s called Singular Vision. A lot of famous people are in it, like Wesley Walker, the receiver for the Jets.”

Mark didn’t mention that he was retired; Derek knew that. He thought he should say he was sorry again. It was like saying his name; he expected it to do something, but it didn’t.

Derek was coming home tomorrow. He could have come home today but they had to fit him with a prosthetic eye.

“It’s not glass,” Derek insisted. “It’s a special kind of plastic they did experiments with on the Space Shuttle. You can drop it fifty feet onto concrete and it won’t chip.”

“Huh,” Mark said.

It was dinner time; a man with a hairnet was rolling a cart down the hall, bringing trays into the rooms. Derek’s had plastic wrap over some kind of chicken. Derek’s mom peeled the plastic off and steam came up.

“I guess we ought to be heading out,” Mark’s mom said, and Derek’s mom walked them out into the hall. “We’ll see you tomorrow, I guess.”

“Oh yeah,” Derek’s mom said. “We’re having a little welcome hom

e party for him.”

“We’ll be there.”

“Thanks for coming,” Derek’s mom said to Mark.

“Sure,” Mark said. Because what else was he supposed to say? You’re welcome?

He thought about all this in bed—which was dumb, he thought. There was nothing he could do about it then.

Tuesday after school Mark helped his mom hang a banner from the porch. It was one she rented out. It said WELCOME HOME and then had a patch where you spelled out the name of the person. Mark handed her the scratchy, Velcro-backed letters from the plastic bin and then held the ladder.

They were all waiting on the porch for him, and then when the Rotas’ truck pulled into the drive they all ran down to the yard. Derek was sitting in the passenger seat; he waited until his stepfather came around to open the door for him.

The patch was gone. At first Mark couldn’t see because his mom was hugging him, and then Sarah, her hair pulled back in a black velvet scrunchy. Derek’s mom was crying a little, and trying to laugh at how sappy she was, and then Derek turned to get a hug from Mark’s dad and Mark could see the eye.

It seemed big, maybe because the lid was puffed-up, and Mark tried not to watch for it to move. It couldn’t, he thought, but he couldn’t be sure, and he didn’t want Derek to catch him staring. But it didn’t look right.

No, because inside when they sat down to have cake, they sat Mark right beside him, on that side. It was like they did it on purpose, so he had to see what he’d done, and so close it was impossible not to see the eye was plastic, and stuck looking straight ahead, no matter who Derek was talking to. To talk to Mark he had to twist around in his chair and look at him over his nose.

“Good cake, huh?”

“Great,” Mark said.

“My mom said you tried on the costumes.”

“Yeah.”

“So, are they like amazing?”

“They have teeth just like you said.”

“Cool.”

“Are you boys ready for the big night?” Mark’s dad asked. ”You got your act down?”

“Oh, forget it,” Derek’s mom joked. “I’m not going anywhere near that place. I’ve had my scare for the year, thank you.”

They all laughed and pitched in to convince her.

“All right,” she said, “but just once.”

It was decided; Mark’s mom would drop them off and then the rest of them would all go together, even Peter and Sarah.

The next morning Derek and Mark got on the bus together. Derek’s eye wasn’t as puffed up, but Philip Dawkins across the aisle wouldn’t stop looking at him.

“What are you staring at?” Derek said.

“You. Your eye.”

And before he knew what he was doing, Mark shot across the aisle and was smashing Philip Dawkins in the face, driving his fist in again and again and growling as Philip’s friends tried to drag him off.

“I’ll kill you,” Philip was saying, but now everyone was staring at him, then looking away, embarrassed for him because blood was coming from his lip and he was crying, even his ears red.

Mark sat rigid in his seat, ready to hit him again if he didn’t shut up. He wouldn’t say anything, he’d just hit him. And when Philip said it again, Mark did. And then no one would look at him.

“What are you doing?” Derek asked.

“He was looking at you.”

“Yeah, so? People are gonna look.”

“I didn’t like what he said either.”

“You didn’t have to hit him again,” Derek said, and the rest of the way they didn’t talk.

“What’s this I hear about a fight on the bus?” his mom said when he got home.

“Nothing,” Mark said. “Someone was making fun of Derek.”

“So you split his lip, is that right?”

“We got in a fight.”

“That’s not the way I heard it. The way I heard it it sounds like you attacked him.”

“It was a fight,” Mark said.

“You make it sound like you’ve been in fights before. Have you?”

“No.”

“Then why now?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well,” his mom said, “why don’t you go up to your room and think about it, and I’ll think about whether you should do your haunted house tonight.”

He didn’t argue, he just went up and closed the door. It was starting to get dark, the sun behind the trees, turning the sky orange. He thought of the gun in pieces in Derek’s basement, in a plastic bag. He still wanted to hit Philip Dawkins, and he would tomorrow if he said anything, he didn’t care.

“Well, have you thought about it?” his mom said when she looked in.

“Yes.”

“And?”

“And I’m sorry,” he said, and this really was a lie.

“You should be,” his mom said, “and if you think you’re sorry now, you just wait till your father hears about this.” She told him to get ready, they were leaving in five minutes.

Derek must have told on him, but on the way over neither of them mentioned the fight. They talked about the Ghost Mine at Kennywood and all the things that jumped out at you, the hiss of air that made your hair stand up just before the end. This was going to be better, Derek said, because there it was the same ride every time; here things could jump out at you from anywhere. Mark was on the side with his good eye but couldn’t stop thinking of the other, the wall of black there, not even blue stars, just nothing.

The haunted house used to be the main building of the old hospital. There was already a long line outside, teenagers and parents with little kids. The fence around the parking lot was covered with giant spiders Mark’s mom made from black garbage bags and old socks. From the trees in front hung ghosts and grinning skeletons. The porch was done up in cobwebs, and speakers on the roof blasted out eerie laughter. Mr. Jenner waved them through to the back lot with a flashlight. Father Don’s mini-van was there, and a bunch of other cars. Mark’s mom got out and came in with them to check on her work.

The hallways were wide but the ceilings were low, and they’d crammed in as much as they could. There were bats that flittered on nylon fishing line, and zombies that peered at you from the rooms, and a mummy who swung down from the ceiling. “Whoa!” Derek said. “Man!” There was an operating room in the real operating room where the doctor cut off the patient’s head, and a torture chamber with an iron maiden and a victim stretched hideously on the rack—all his mom’s work. She bent over the displays, straightening things, touching up. Right now it looked stupid, but in the dark with the dry ice fog sliding along the floor it would be scary, or that was the idea. Last year when they went through, Mark had stayed close to his dad, hoping he wouldn’t notice. None of it was really scary, it was all fake; it was just that he didn’t like being frightened. It was stupid to be frightened of that stuff, he thought; there were real things to be afraid of.

Father Don was putting on his costume—the lab coat and wire glasses of Dr. Frankenstein. Mark’s mom told him everything looked okay and that she’d see them later and left them with him.

“Let me show you where you are,” Father Don said, and took them upstairs.

They had a room of their own, made up to look like the ocean, the walls covered in wavy, mirrored paper with a blue light shining on it, an inflatable shark in one corner, fake seaweed and cardboard starfish everywhere. There were mossy papier-mâché rocks with a crack you had to squeeze through to get to the next room; that’s where they’d scare people.

“Cool,” Derek said when he saw the suits, and Mark wished he’d stop being so stupid.

“Okay, I’ll let you two get settled. We should be starting in about ten minutes. They’ll be an announcement on the PA.”

“Wow,” Derek said, and looked around the room, turning in a circle. The foil and the blue light made the room seem bigger. He went to the stairs and then came back. “Check this out,” he whispered, and pulled a small white tub

e from his pocket and handed it to Mark.

It was Vampire Blood, Mark had seen some in the novelty shop downtown, thin runny stuff the color of maraschino cherries.

“What are you going to do with it?” Mark asked.

“We’ll put it on, it’ll be scarier.”

“You shouldn’t put it on the costumes.”

“Look,” Derek said, and pointed to where it said Does Not Stain Clothing. “Okay?”

“Whatever.”

“Whatever,” Derek echoed him.

“Shut up,” Mark said, and threw the tube at him.

As soon as it left his hand, he was sure it would hit him in the other eye. He didn’t mean it; he didn’t know why he was angry. Everything.

The tube flew past Derek and skittered under the shark.

“What was that for?” Derek said.

“Nothing. I’m sorry.”

“You should be,” Derek said, and retrieved it.

They didn’t say anything while they hauled their suits on.

“Here,” Mark said, and zipped him up, helped him settle the head.

“It’s heavy,” Derek said. “Can you see anything?”

“Not much.”

The announcement came over the PA and someone’s dad ran up the stairs and left a bucket with a chunk of dry ice steaming in the corner. Derek held up the Vampire Blood.

“You want some?”

“Sure,” Mark said, more to be nice than anything. It would probably look cheesy; all that stuff did.

Derek held the front of the mask and for a minute all Mark could see were his hands and the tube. The lights flickered and finally stayed on, but just barely. With the blue light it almost looked liked they were underwater.

“How about your claws?”

“Why not,” Mark said, and held out his arms. He waited inside the suit and then Derek let go of one hand and took the other.

“Well,” Mark said, “how’s it look?”

“See for yourself.” Derek led him forward a few steps and then turned him toward the wall.

There in the wavy mirror stood the Creature from the Black Lagoon, its lips bright with blood. Mark raised his claws and growled, then did it again, leaning closer, and again, till he was inches from it, his breath coming back off the wall. The foil distorted his face, made the Creature’s eyes bulge and slither, his fangs grow. Mark tilted his chin until he could see himself inside the mouth, his eyes looking back at the monster that had devoured him. In the mirror, in the dim light, with the fog rolling all around him, Mark thought it looked very real.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

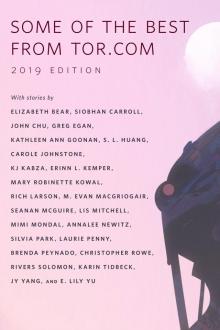

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

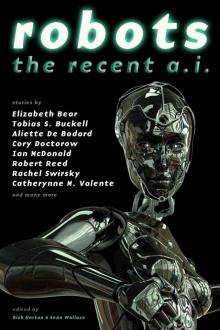

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3