- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Robots: The Recent A.I. Page 9

Robots: The Recent A.I. Read online

Page 9

He was suddenly very, very angry.

He stepped away from her and had a seat. She sat, too.

“Well,” she said, gesturing around the room. The robots, the safe house, the death penalty, the abandoned daughter and the decade-long defection, all of it down to “well” and a flop of a hand-gesture.

“Natalie Judith Goldberg,” he said, “it is my duty as a UNATS Detective Third Grade to inform you that you are under arrest for high treason. You have the following rights: to a trial per current rules of due process; to be free from self-incrimination in the absence of a court order to the contrary; to consult with a Social Harmony advocate; and to a speedy arraignment. Do you understand your rights?”

“Oh, Daddy,” Ada said.

He turned and fixed her in his cold stare. “Be silent, Ada Trouble Icaza de Arana-Goldberg. Not one word.” In the cop voice. She shrank back as though slapped.

“Do you understand your rights?”

“Yes,” Natalie said. “I understand my rights. Congratulations on your promotion, Arturo.”

“Please ask your robots to stand down and return my goods. I’m bringing you in now.”

“I’m sorry, Arturo,” she said. “But that’s not going to happen.”

He stood up and in a second both of her robots had his arms. Ada screamed and ran forward and began to rhythmically pound one of them with a stool from the breakfast nook, making a dull thudding sound. The robot took the stool from her and held it out of her reach.

“Let him go,” Natalie said. The robots still held him fast. “Please,” she said. “Let him go. He won’t harm me.”

The robot on his left let go, and the robot on his right did, too. It set down the dented stool.

“Artie, please sit down and talk with me for a little while. Please.”

He rubbed his biceps. “Return my belongings to me,” he said.

“Sit, please?”

“Natalie, my daughter was kidnapped, I was gassed and I have been robbed. I will not be made to feel unreasonable for demanding that my goods be returned to me before I talk with you.”

She sighed and crossed to the hall closet and handed him his wallet, his phone, Ada’s phone, and his sidearm.

Immediately, he drew it and pointed it at her. “Keep your hands where I can see them. You robots, stand down and keep back.”

A second later, he was sitting on the carpet, his hand and wrist stinging fiercely. He felt like someone had rung his head like a gong. Benny—or the other robot—was beside him, methodically crushing his sidearm. “I could have stopped you,” Benny said, “I knew you would draw your gun. But I wanted to show you I was faster and stronger, not just smarter.”

“The next time you touch me,” Arturo began, then stopped. The next time the robot touched him, he would come out the worse for wear, same as last time. Same as the sun rose and set. It was stronger, faster and smarter than him. Lots.

He climbed to his feet and refused Natalie’s arm, making his way back to the sofa in the living room.

“What do you want to say to me, Natalie?”

She sat down. There were tears glistening in her eyes. “Oh God, Arturo, what can I say? Sorry, of course. Sorry I left you and our daughter. I have reasons for what I did, but nothing excuses it. I won’t ask for your forgiveness. But will you hear me out if I explain why I did what I did?”

“I don’t have a choice,” he said. “That’s clear.”

Ada insinuated herself onto the sofa and under his arm. Her bony shoulder felt better than anything in the world. He held her to him.

“If I could think of a way to give you a choice in this, I would,” she said. “Have you ever wondered why UNATS hasn’t lost the war? Eurasian robots could fight the war on every front without respite. They’d win every battle. You’ve seen Benny and Lenny in action. They’re not considered particularly powerful by Eurasian standards.

“If we wanted to win the war, we could just kill every soldier you sent up against us so quickly that he wouldn’t even know he was in danger until he was gasping out his last breath. We could selectively kill officers, or right-handed fighters, or snipers, or soldiers whose names started with the letter ‘G.’ UNATS soldiers are like cavemen before us. They fight with their hands tied behind their backs by the three laws.

“So why aren’t we winning the war?”

“Because you’re a corrupt dictatorship, that’s why,” he said. “Your soldiers are demoralized. Your robots are insane.”

“You live in a country where it is illegal to express certain mathematics in software, where state apparatchiks regulate all innovation, where inconvenient science is criminalized, where whole avenues of experimentation and research are shut down in the service of a half-baked superstition about the moral qualities of your three laws, and you call my home corrupt? Arturo, what happened to you? You weren’t always this susceptible to the Big Lie.”

“And you didn’t use to be the kind of woman who abandoned her family,” he said.

“The reason we’re not winning the war is that we don’t want to hurt people, but we do want to destroy your awful, stupid state. So we fight to destroy as much of your materiel as possible with as few casualties as possible.

“You live in a failed state, Arturo. In every field, you lag Eurasia and CAFTA: medicine, art, literature, physics . . . All of them are subsets of computational science and your computational science is more superstition than science. I should know. In Eurasia, I have collaborators, some of whom are human, some of whom are positronic, and some of whom are a little of both—”

He jolted involuntarily, as a phobia he hadn’t known he possessed reared up. A little of both? He pictured the back of a man’s skull with a spill of positronic circuitry bulging out of it like a tumor.

“Everyone at UNATS Robotics R&D knows this. We’ve known it forever: when I was here, I’d get called in to work on military intelligence forensics of captured Eurasian brains. I didn’t know it then, but the Eurasian robots are engineered to allow themselves to be captured a certain percentage of the time, just so that scientists like me can get an idea of how screwed up this country is. We’d pull these things apart and know that UNATS Robotics was the worst, most backwards research outfit in the world.

“But even with all that, I wouldn’t have left if I didn’t have to. I’d been called in to work on a positronic brain—an instance of the hive-intelligence that Benny and Lenny are part of, as a matter of fact—that had been brought back from the Outer Hebrides. We’d pulled it out of its body and plugged it into a basic life-support system, and my job was to find its vulnerabilities. Instead, I became its friend. It’s got a good sense of humor, and as my pregnancy got bigger and bigger, it talked to me about the way that children are raised in Eurasia, with every advantage, with human and positronic playmates, with the promise of going to the stars.

“And then I found out that Social Harmony had been spying on me. They had Eurasian-derived bugs, things that I’d never seen before, but the man from Social Harmony who came to me showed it to me and told me what would happen to me—to you, to our daughter—if I didn’t cooperate. They wanted me to be a part of a secret unit of Social Harmony researchers who build non-three-laws positronics for internal use by the state, anti-personnel robots used to put down uprisings and torture-robots for use in questioning dissidents.

“And that’s when I left. Without a word, I left my beautiful baby daughter and my wonderful husband, because I knew that once I was in the clutches of Social Harmony, it would only get worse, and I knew that if I stayed and refused, that they’d hurt you to get at me. I defected, and that’s why, and I know it’s just a reason, and not an excuse, but it’s all I’ve got, Artie.”

Benny—or Lenny?—glided silently to her side and put its hand on her shoulder and gave it a comforting squeeze.

“Detective,” it said, “your wife is the most brilliant human scientist working in Eurasia today. Her work has revolutionized our society a d

ozen times over, and it’s saved countless lives in the war. My own intelligence has been improved time and again by her advances in positronics, and now there are a half-billion instances of me running in parallel, synching and integrating when the chance occurs. My massive parallelization has led to new understandings of human cognition as well, providing a boon to brain-damaged and developmentally disabled human beings, something I’m quite proud of. I love your wife, Detective, as do my half-billion siblings, as do the seven billion Eurasians who owe their quality of life to her.

“I almost didn’t let her come here, because of the danger she faced in returning to this barbaric land, but she convinced me that she could never be happy without her husband and daughter. I apologize if I hurt you earlier, and beg your forgiveness. Please consider what your wife has to say without prejudice, for her sake and for your own.”

Its featureless face was made incongruous by the warm tone in its voice, and the way it held out its imploring arms to him was eerily human.

Arturo stood up. He had tears running down his face, though he hadn’t cried when his wife had left him alone. He hadn’t cried since his father died, the year before he met Natalie riding her bike down the Lakeshore trail, and she stopped to help him fix his tire.

“Dad?” Ada said, squeezing his hand.

He snuffled back his snot and ground at the tears in his eyes.

“Arturo?” Natalie said.

He held Ada to him.

“Not this way,” he said.

“Not what way?” Natalie asked. She was crying too, now.

“Not by kidnapping us, not by dragging us away from our homes and lives. You’ve told me what you have to tell me, and I will think about it, but I won’t leave my home and my mother and my job and move to the other side of the world. I won’t. I will think about it. You can give me a way to get in touch with you and I’ll let you know what I decide. And Ada will come with me.”

“No!” Ada said. “I’m going with Mom.” She pulled away from him and ran to her mother.

“You don’t get a vote, daughter. And neither does she. She gave up her vote twelve years ago, and you’re too young to get one.”

“I fucking HATE you,” Ada screamed, her eyes bulging, her neck standing out in cords. “HATE YOU!”

Natalie gathered her to her bosom, stroked her black curls.

One robot put its arms around Natalie’s shoulders and gave her a squeeze. The three of them, robot, wife and daughter, looked like a family for a moment.

“Ada,” he said, and held out his hand. He refused to let a note of pleading enter his voice.

Her mother let her go.

“I don’t know if I can come back for you,” Natalie said. “It’s not safe. Social Harmony is using more and more Eurasian technology, they’re not as primitive as the military and the police here.” She gave Ada a shove, and she came to his arms.

“If you want to contact us, you will,” he said.

He didn’t want to risk having Ada dig her heels in. He lifted her onto his hip—she was heavy, it had been years since he’d tried this last—and carried her out.

It was six months before Ada went missing again. She’d been increasingly moody and sullen, and he’d chalked it up to puberty. She’d cancelled most of their daddy-daughter dates, moreso after his mother died. There had been a few evenings when he’d come home and found her gone, and used the location-bug he’d left in place on her phone to track her down at a friend’s house or in a park or hanging out at the Peanut Plaza.

But this time, after two hours had gone by, he tried looking up her bug and found it out of service. He tried to call up its logs, but they ended at her school at 3 P.M. sharp.

He was already in a bad mood from spending the day arresting punk kids selling electronics off of blankets on the city’s busy street, often to hoots of disapprobation from the crowds who told him off for wasting the public’s dollar on petty crime. The Social Harmony man had instructed him to give little lectures on the interoperability of Eurasian positronics and the insidious dangers thereof, but all Arturo wanted to do was pick up his perps and bring them in. Interacting with yammerheads from the tax-base was a politician’s job, not a copper’s.

Now his daughter had figured out how to switch off the bug in her phone and had snuck away to get up to who-knew-what kind of trouble. He stewed at the kitchen table, regarding the old tin soldiers he’d brought home as the gift for their daddy-daughter date, then he got out his phone and looked up Liam’s bug.

He’d never switched off the kid’s phone-bug, and now he was able to haul out the UNATS Robotics computer and dump it all into a log-analysis program along with Ada’s logs, see if the two of them had been spending much time in the same place.

They had. They’d been physically meeting up weekly or more frequently, at the Peanut Plaza and in the ravine. Arturo had suspected as much. Now he checked Liam’s bug—if the kid wasn’t with his daughter, he might know where she was.

It was a Friday night, and the kid was at the movies, at Fairview Mall. He’d sat down in auditorium two half an hour ago, and had gotten up to pee once already. Arturo slipped the toy soldiers into the pocket of his winter parka and pulled on a hat and gloves and set off for the mall.

The stink of the smellie movie clogged his nose, a cacophony of blood, gore, perfume and flowers, the only smells that Hollywood ever really perfected. Liam was kissing a girl in the dark, but it wasn’t Ada, it was a sad, skinny thing with a lazy eye and skin worse than Liam’s. She gawked at Arturo as he hauled Liam out of his seat, but a flash of Arturo’s badge shut her up.

“Hello, Liam,” he said, once he had the kid in the commandeered manager’s office.

“God damn, what the fuck did I ever do to you?” the kid said. Arturo knew that when kids started cursing like that, they were scared of something.

“Where has Ada gone, Liam?”

“Haven’t seen her in months,” he said.

“I have been bugging you ever since I found out you existed. Every one of your movements has been logged. I know where you’ve been and when. And I know where my daughter has been, too. Try again.”

Liam made a disgusted face. “You are a complete ball of shit,” he said. “Where do you get off spying on people like me?”

“I’m a police detective, Liam,” he said. “It’s my job.”

“What about privacy?”

“What have you got to hide?”

The kid slumped back in his chair. “We’ve been renting out the OLED clothes. Making some pocket money. Come on, are infra-red lights a crime now?”

“I’m sure they are,” Arturo said. “And if you can’t tell me where to find my daughter, I think it’s a crime I’ll arrest you for.”

“She has another phone,” Liam said. “Not listed in her name.”

“Stolen, you mean.” His daughter, peddling Eurasian infowar tech through a stolen phone. His ex-wife, the queen of the super-intelligent hive minds of Eurasian robots.

“No, not stolen. Made out of parts. There’s a guy. The code for getting on the network was in a phone book that we started finding last month.”

“Give me the number, Liam,” Arturo said, taking out his phone.

“Hello?” It was a man’s voice, adult.

“Who is this?”

“Who is this?”

Arturo used his cop’s voice: “This is Arturo Icaza de Arana-Goldberg, Police Detective Third Grade. Who am I speaking to?”

“Hello, Detective,” said the voice, and he placed it then. The Social Harmony man, bald and rounded, with his long nose and sharp Adam’s apple. His heart thudded in his chest.

“Hello, sir,” he said. It sounded like a squeak to him.

“You can just stay there, Detective. Someone will be along in a moment to get you. We have your daughter.”

The robot that wrenched off the door of his car was black and non-reflective, headless and eight-armed. It grabbed him without ceremony and dragged him fr

om the car without heed for his shout of pain. “Put me down!” he said, hoping that this robot that so blithely ignored the first law would still obey the second. No such luck.

It cocooned him in four of its arms and set off cross-country, dancing off the roofs of houses, hopping invisibly from lamp-post to lamp-post, above the oblivious heads of the crowds below. The icy wind howled in Arturo’s bare ears, froze the tip of his nose and numbed his fingers. They rocketed downtown so fast that they were there in ten minutes, bounding along the lakeshore toward the Social Harmony center out on Cherry Beach. People who paid a visit to the Social Harmony center never talked about what they found there.

It scampered into a loading bay behind the building and carried Arturo quickly through windowless corridors lit with even, sourceless illumination, up three flights of stairs and then deposited him before a thick door, which slid aside with a hushed hiss.

“Hello, Detective,” the Social Harmony man said.

“Dad!” Ada said. He couldn’t see her, but he could hear that she had been crying. He nearly hauled off and popped the man one on the tip of his narrow chin, but before he could do more than twitch, the black robot had both his wrists in bondage.

“Come in,” the Social Harmony man said, making a sweeping gesture and standing aside while the black robot brought him into the interrogation room.

Ada had been crying. She was wrapped in two coils of black-robot arms, and her eyes were red-rimmed and puffy. He stared hard at her as she looked back at him.

“Are you hurt?” he said.

“No,” she said.

“All right,” he said.

He looked at the Social Harmony man, who wasn’t smirking, just watching curiously.

“Leonard MacPherson,” he said, “it is my duty as a UNATS Detective Third Grade to inform you that you are under arrest for trade in contraband positronics. You have the following rights: to a trial per current rules of due process; to be free from self-incrimination in the absence of a court order to the contrary; to consult with a Social Harmony advocate; and to a speedy arraignment. Do you understand your rights?”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

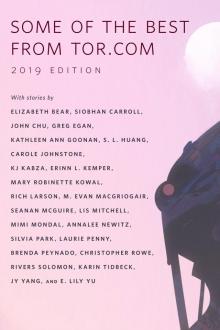

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3