- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

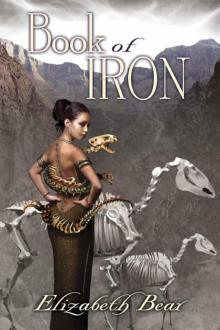

Book of Iron bajc-2 Page 4

Book of Iron bajc-2 Read online

Page 4

“Right,” Salamander agreed, quite reasonably. “One nightmare at a time, then.”

Her calm courage sent a pang of respect through Bijou. If she were to compete, not for Kaulas, but for Salamander’s friendship—

But such a decision would tear the Beyzade’s little party of adventurers apart as surely as a man quartered between horses. And what they did was important. They conquered dangers no one else could even approach.

One of the dead horses stalked up. Bijou was only a few canes distant from Salamander now. “Keep backing up,” Bijou called. Another four steps, five, and they would be side by side.

“They’re almost upon you,” Kaulas called. Ambrosias reared up and rattled itself mightily, sending a warning shiver of sound across the sand.

Salamander gasped with effort, leaning forward in her determination, her open hands thrust wide. Through gritted teeth, she panted, “Too many of them. I can’t…hold the shadows back.”

As if a giant pressed against Salamander’s palms, her elbows folded. She could fall back no further: with every step she gave, the shadows took two. They loomed close enough now that Bijou could see the gaunt shapes within, the yellow eyes gleaming with gathered moonlight. In the shadows, she couldn’t make out individuals: just a black silhouette of pricked ears and clawed hands, yearning.

Bijou made the dead horse whirl and kick, but it was slow and clumsy. In such things, she was a puppeteer at best, and these were not moves she had practiced.

“Let me,” Kaulas called.

Normally, she’d hesitate to encourage him to raise up the shade of something so far decayed, but this was war. She released the wizardry with which she bound the horse-corpse, and felt Kaulas effortlessly pick up the threads before it could fall. Now the undead steed came alive, dry neck arching, hooves thumping the earth in a manner that could only be interpreted as a gesture of war. It threw up its head and shook out the sad, strawtick remnants of its mane. From its motion, Bijou imagined the fierce war-whistle of an angry stallion, but only the rattle of sinew and bone reached her ears.

The arrogant prance and kick of long, clean legs weathered down to brown bone broke her heart as no puppet-mastered corpse ever could.

The ghuls were not afraid of dead things. But even they must respect the flashing hooves of an angry horse—two, when the second corpse joined the first. A mare, Bijou thought, watching this one standing stolid and low-headed, sand blown from the jagged cavities where its nostrils once had flared. The shadows still stretched to encompass the defiant horses, though, and Bijou saw the undead mare twist her bony neck around and snap at a ghul-hand that clawed her shoulder.

Bijou reached out and grasped Salamander’s shoulder, her fingers bunching cloth and sliding over the firm muscle beneath. Bijou saw Ambrosias’s ferret-skulled head snap forward and rattle back, muzzle stained darker now, and wished—not for the last time—that she had thought to give it venom. As if Bijou’s touch gave her strength, Salamander incrementally managed to straighten her arms again. Bijou leaned forward, heart hammering, willing the other woman strength.

The pressure did not push the shadows back. But it pushed Salamander away from them, into Bijou’s arms. With that grip and the rear-guard of the horses and Ambrosias, Bijou managed to pull Salamander in retreat before the rising shadows. Shoes scuffling, sand sifting down over the tops of their boots, the women regained the circle of their allies.

As soon as Bijou and Salamander were clear, Ambrosias turned like a twisted ribbon and came back, legs wearing a rippled track in the sand. As Bijou released her grip on Salamander, Ambrosias swarmed up its mistress’ leg and spine until it hooded her head, knocking her hat on its strings down her back and rearing up like a pharaoh’s cobra crown.

The shadows lapped higher. Salamander, fumbling in her pocket, pulled out the torch. But before her thumb found the switch, Maledysaunte stepped into the gap in the circle, up to the edge of the ringing dark, and with her hands fisted at her sides cried out in a voice and a tongue that curled Bijou’s soul like a dry leaf and made her hot blood as ash in her veins.

The words were ancient and oily, liquid and barbed. Bijou’s stomach tightened against them. She could not get a breath. It was as if all life and light died within her, scraped from her body like nectar from a flower, leaving only the husk behind.

The shadows broke like waves on stone. Then they began to heap, climbing impossibly, as if piled against a wall of glass. They rose quickly as water running into a cistern when the gate is raised. Bijou saw Maledysaunte take a breath and square her shoulders, and more terrible words ripped from her like a torrent of wind.

The shadows before her were torn back, blown aside as if by an explosion. The corpse of the valiant mare, still snorting and kicking savagely as the shadows heaped over her, was blasted to splinters.

Bijou saw the ghuls clearly as their shrouds of darkness were ripped from them. The words did not seem to harm them, creatures of Ancient Erem that they were, only shredded them clean—but they seemed ridiculous in the naked moonlight. Nude, gaunt creatures that walked on a dog’s misshapen paws, long ears cringing over the projecting bones of their shoulders, velvet-fuzzed grey skin mole-soft and defenseless. Their claws and teeth shone terrible, but their faces and bodies were frail. They minded Bijou of the big-eyed, hairless hounds some very rich men kept as evidence of their wealth: pitiful things that could bear neither sun nor cold without protection.

In the aftermath of the power of Maledysaunte’s words, the ghuls straightened slowly, facing her, quiet with fear or surprise. What remained of the shadows they had commanded crazed, cracked, fell to dust and rolled back into the night. The red and ivory moons shone bright as lamps between stars that gleamed like the fires of a distant army, and all that light spilled down over a scene as still and orderly as an army of statues. Even the wind had died, and with it the ceaseless sifting of one sand grain over another.

“That was the language of Erem,” Kaulas whispered. It carried in the silence. “How can you read it and see? How can you speak it and live?”

Maledysaunte turned her head and spat three rotten teeth upon the ground. The strands of her black hair that had blown across her face were bleached white and brittle. When she wiped her mouth, the back of her hand streaked dark and Bijou caught the rust-reek of clotted blood. Her lips, never lush, had withered like an old woman’s, her youthful skin drawn up crêpey and puckered as if she were the toothless hag legend held her.

Four

Maledysaunte glanced at Kaulas and touched her throat with two fingers, shaking her head lightly.

“She can’t speak now,” Riordan translated unnecessarily. “Not until her voice grows back.”

“Grows…back?”

The bard spoke as mildly as butter. “She is an immortal, Wizard Kaulas. She will heal.”

Bijou would have given anything to see the expression on Kaulas’ face behind the veil. Just a glimpse of the thin band of nakedness revealing his eyes showed her awe and avarice.

He glanced quickly aside, as if he did not care to see her reading him. “It wasn’t this bad last time,” he said, voice still muffled by his veil.

“Indeed.” Prince Salih pulled a fold of cloth across his face as if in unconscious imitation of the necromancer. “Would you say that something has their guard up?”

“I’d say,” said Salamander. She reached to take Maledysaunte’s arm. The necromancer shook her off and stepped forward, making a hooking gesture with her left hand. Follow.

She led them across the trampled sand, down into the center of Ancient Erem. The ghuls drew back before her. They lined the path, enormous eyes staring. Bijou found herself walking with the others, three abreast in two ranks. They measured their strides. The stamping, undead stallion followed them, shying and switching his tail as if the flies had not long ago had their way with him. Ambrosias lay flat and scrunched its forelegs into the cushion of Bijou’s hair.

A line of cold froze her spi

ne straight and stiff. She had made such a promenade before, down lines of hostile observers, at the beginning of the long walk that had brought her to Messaline as a girl.

She hoped this time the pejorative gazes would not be reinforced with hurled stones.

One ghul, gray and starveling as the others, pushed through to the front rank and prostrated itself before Maledysaunte. It hissed; it glibbered. Prince Salih moved forward, ready to intervene, but the ghul came no closer as Maledysaunte checked her step. Her lips formed words; no sound emerged. But its eyes watched the shapes her mouth made avidly, and it answered.

“It wants to know,” said Kaulas, who spoke the language of ghuls, “if we seek the treasure-hunter. If we do, it says she went beyond the water.”

“Do you trust a ghul?” Salamander said.

Kaulas and Maledysaunte, as one, shook their heads.

The ghul retreated, scuttling backwards on all fours. Bijou started forward again as if it had not accosted them. Out of the corner of her mouth, she spoke to Salamander and Maledysaunte as they came up beside her. “So, what say you tell us exactly what it was that Dr. Liebelos did, in Avalon? And what the results were?”

Maledysaunte just shook her head. No sound from her lips: not yet anyway. Bijou kept an ear on the footsteps of the men close behind them, but she wouldn’t turn her head to see them. Instead she cleared her throat, a sound meant for encouragement. With some urging—it was heavy, being made of stone and metal and bone—Ambrosias slid back down Bijou’s body and twined through the sand beside her.

From beyond Maledysaunte, the Wizard Salamander spoke reluctantly. “You’ve heard of the Glass Book of Erem?”

Despite herself, Bijou could not quite hold back the chuckle. “It figures prominently in the history of Messaline.”

“There’s another such text.”

The moonlight was so bright that Bijou could see the color rise in Maledysaunte’s white cheeks. It stood out in stark, discrete spots like the rouge on a porcelain doll from the outermost East. Her eyes flicked again, following some movement that Bijou could not. This time, Bijou understood it, and wondered how long one could endure, aware of things no one else could perceive, before it drove one mad.

“I see,” Bijou said.

“The Iron Book of Erem. Also called the Black Book of Erem.”

“Where is it?”

“Nowhere in the world, any more.”

“Destroyed?”

“No,” Salamander said.

From the set of Maledysaunte’s chin, Bijou imagined she understood what the Hag of Wolf Wood was feeling. Bijou knew what exile felt like, the repudiation of one’s family. But Maledysaunte’s pride and distress were clues, and Bijou could not afford to pass those up, currently.

“I think,” Bijou said, as they passed the last rank of ghuls, who turned to watch their backs retreating as they walked deeper into Ancient Erem, “that we’ve earned a few answers.”

“When the Black Book has been read, it translates itself.”

“Into…another language?”

The footsteps of the men grew ragged as they began to climb a slope to the lowest terrace of stone houses. The undead stallion’s hooves slid in sand.

“Into the soul of whoever read it. It ceases to exist in the external world. In a very real sense, that reader becomes the book. And there it remains until that reader dies.”

Bijou actually blinked, understanding running hot and habituating through her veins. The rush cleared her of the pall of sorrow and cobwebs Maledysaunte’s incantation had left behind. She drew a deeper breath in reaction, thinking of rotten teeth and withered skin. “Which usually happens quite quickly, I imagine.”

“I imagine,” Salamander agreed.

“But Maledysaunte is immortal.”

“She is.”

Behind them, Kaulas cleared his throat. “That doesn’t explain what brings your mother here, however.”

Finally, a dim smile flickered across Salamander’s face. Bijou caught it from the corner of her eye. “It’s said that the one way to win the Book free of its…host…is to summon it back to the anvil where it was forged.”

“Here in Erem,” Kaulas said.

“Here in Erem.”

Prince Salih asked, “What would that do to the host?”

Maledysaunte turned over her shoulder and smiled, a terrible grin that showed the gaps in her teeth and her blackened tongue.

“I see,” said Salih.

“You could have warned us in advance,” Kaulas said dryly. “Instead of spinning tales—”

“Spinning tales is what I do. Besides, would you have helped us then?” Riordan asked.

“We’re heroes,” Salih said.

Bijou shot Kaulas a sharp glare when he laughed.

They came to a funnel-shaped depression in the ground. Bijou turned left to skirt it.

“Watch out for that,” said Prince Salih to the newcomers, interposing himself, one hand on the hilt of his scimitar. Gently, he laid the other fingertips on Maledysaunte’s arm to guide her away. She turned to him, eyes wide with surprise, and Bijou did not think it was offense. She was just shocked that anyone would touch her so informally, so without thought.

The flesh around her mouth was already plumping again.

“Myrmecoleon pit-trap,” he explained gently. “If you fall in, you slide to the bottom—”

“Oh,” she said, her voice rusty and worn—but present, and that was something. She swallowed wincingly. “That’s not in the book.”

Wordlessly, Bijou held out her water-bottle, and watched as the Hag of Wolf Wood took a painful sip.

“Maybe they’re new,” said the prince.

She rinsed the water around her mouth, swallowed, and said, “So. I suppose we’re looking for the blacksmith’s shop.”

“Of course,” the prince answered. “Where else would you keep your anvil?”

Logic led them, along with the memories of Bijou and Prince Salih. An anvil would be on the ground floor; a forge would be well-vented. They decided rapidly that neither was likely to be located in the terraced houses stacked one tier on the next in the sandstone hills, turning instead to the largest excavations—the ones with pillared facades stretching up into the cliff-heights. But poking among them at random proved unhelpful, and every one of the adventurers was too aware of the lurking ghuls and of the remaining duration of the night wearing thin.

“There are a dozen,” Riordan said. “Did your spider have better intelligence than we’re likely to gain by choosing at random?”

“What about what the ghul said?” Riordan asked.

“A forge would be near water.” Bijou volunteered the information as she realized it, having some experience with such things.

Salamander nodded. “I’m afraid my new friend was left behind in the stampede. But I got a sense of water from her, yes.”

“Good,” said the prince. “Water is this way.”

“How do you know that?” Riordan asked—nevertheless following unhesitatingly.

They hadn’t made it this far into the city last time. And there were no maps of Ancient Erem—none remaining, anyway, to Bijou’s knowledge.

“Can’t you smell it?” It was a testament to the prince’s diplomatic skills that no trace of helpless wetlanders crossed his expression. Bijou was glad Kaulas went veiled, after all: there were none so scornful as those who had had to learn the hard way.

“Is that what that metal smell is?” Salamander asked.

“Yes,” said Bijou.

“Then yes,” she said. “I can.”

The way tended downhill again, which was a good sign, and the night still darkened. Moons set, and soon they were walking only by starlight—but the starlight was enough. They avoided two more myrmecoleon dens, eventually coming upon a tall tongue of sandstone riddled with tunneled doorways. They might once have had rectangular corners, but over centuries the wind and sand had worn their edges smooth. The path downward led them aro

und it, and here the drifted sand had blown back from an ancient road paved with cracked white slabs of stone.

As they walked, Bijou became aware of the brightening of the sky, even though the moons had long slid out of it. At one horizon—not where she thought East lay, in reference to Messaline—a dim glow appeared behind the canyon walls—a line of peach and gold and lavender tracing the top of the cliff face.

Salamander looked at her. “Should we be taking cover?”

“We’ll have a little while no matter which sun it is,” Bijou said. “I’d rather find your mother before she…”

…has time to kill your friend.

Salamander nodded.

Bijou said, “Pray one of the white suns rises first. If your gods are the amenable sort, pray that it’s just the nightsun, and we’re in a year where it rises far in advance of the others.”

“How many suns are there?” Riordan said.

“Four,” said Maledysaunte. “Three daysuns—the blue, the orange, and the white—and the nightsun, which is white also. The daysuns rise and set together; it is the blue one whose light is so feared. Sometimes the orange sun eclipses it, which is safer. A little. The nightsun is a wanderer. Like the moon of Messaline and the moon of Avalon, sometimes it shines alone in the dark, and sometimes it shines with its sisters. There is a pattern to its meanderings,” she finished. “But it lasts a little over 1,864 years. And I’m not sure where we are within it. Once I get a look at the suns, I’ll know better…”

The others had paused to stare, the dead stallion tossing his head in impatience as he checked his stride to avoid trampling Kaulas.

“Of course,” the prince said to break the silence. “It’s all in the book.”

“The Book. The burning Book, the Black Book. The Book of flame. The Book, the Book, the Book.” Her child-soft lips twisted apologetically. “My head is full of it. I could tell you their names in the Ancient Tongue—”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

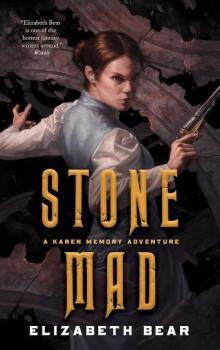

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

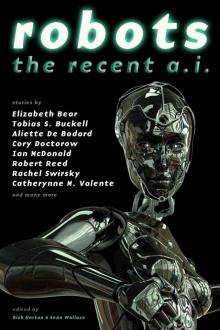

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3