- Home

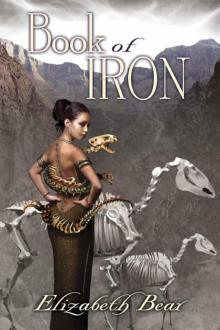

- Elizabeth Bear

Book of Iron bajc-2 Page 5

Book of Iron bajc-2 Read online

Page 5

“Thank you,” Salamander said hastily. “All the same.”

Despite the pale light creeping up the sky, Bijou smiled. These foreign wizards had a sense of humor after all. Even if it involved a language whose every syllable was murder.

The adventurers rounded the end of that sandstone tongue and found themselves looking down into a deeper, narrower, and more shadowed canyon. Serried ranks of broken-topped pillars marched its width and length, showing that the whole thing had once been roofed in stone to form a hypostyle.

“They built in the valleys to stay out of the suns,” Riordan said. “Gods, what a life.”

“And what a death,” Kaulas added. “They’re all gone now, and what they built….” He shrugged.

They could not see a sun yet, but a pale brightness—like the light of four moons—crept down one canyon wall: the first light of the nightsun, Bijou hoped. The sky had not paled much beyond that dusty mauve they’d seen on arriving, and she thought it was not yet bright enough to herald the white daystar. Also the air still held the morning cool.

“I think we’re in luck,” said Prince Salih. “Or the gods are with us.”

“You trust them not to change their minds?”

“I think that ghul was trying to trick us,” Riordan said.

Bijou shook her head. “Why should it, when it could lead us to our deaths simply by telling the truth?”

She broke into a shuffling trot, her kaftan trailing in the air behind. Running on dry sand was no joy: her calves ached within strides and the sand that had sifted into her boot gritted between the sock and her sole. But she concentrated on steadying her stride and her ankles as the others fell in. She could see the lakebed now, baked dry, with the fragments of stone roof that had once protected it half-embedded in the hardpan. It was difficult to judge how far away objects lay in such a desert, with no haze to blur distant things, but Bijou guessed the hardpan ended no more than an eighth of a league on—in the long, low arch of a cavern behind it. In that deep shade, Bijou could just discern the glisten of water.

Limping heavily, Riordan was falling behind as they ran until Kaulas stopped the dead horse and let him mount. The bard might have been dubious before, but it wasn’t because he didn’t know how to ride. He vaulted onto the stallion’s back with the same agility he’d shown exiting the roadster, and then he was in the lead at a rocking-chair canter. Clothing flapping, water bottles sloshing, the others raced after.

Bijou felt the air warming as she ran, the too-swift brightening of the rock wall—top to bottom—and then the sand at its foot as the nightsun slid over the edge of the cliff. It might have seemed no more than a star—it was a speck, surely no larger than a very bright planet against the fixéd heavens, and if it had any diameter its width was lost in its glare—but it was brighter than four full moons, easily bright enough to wash the velvet purple-black from the night and bleach it a heavy shade of lilac.

As the nightsun’s rays caught Bijou she shaded her eyes reflexively, but in truth there was no need. The light was no more than a bright candle held over her shoulder, and far from enough to make her squint. What worried her was that the sky continued to brighten behind the nightsun’s rising, incandescent lashings of molten gold and crimson staining half the shard of sky they could see from down in the canyon where they ran. She’d have pulled her hat up, but it wouldn’t stay on her head while she ran.

“I hope you brought a parasol,” Maledysaunte panted between steps. They were almost there. Less than a hundred canes distant, Riordan was already gentling the undead horse to a walk in safe shadow while those behind him pelted for safety.

“Smoked glass,” Salamander gasped back.

“Polarizing filter,” said Bijou, groping beneath her kaftan. The daysuns wouldn’t kill her instantly, and the scientist in her cried out for a glimpse. To come so far, to stand under the last memory of the sky of a destroyed kingdom—what Wizard could resist?

They hadn’t stayed for sunrise the last time they were here.

The sky overhead faded, and kept fading—through amethyst, orchid, lavender, to a horrible pallid shade, a white all dusty thistle-gray along the rim of the canyon. The heat fell down upon them, although the canyon was some protection: the cool air was trapped here and the savage heat only radiated in. Light burned down the canyon wall, brighter than any sun Bijou had ever seen, brighter by far than the twin suns of her childhood home.

Bijou thudded into the shade of the cavern with sweat washing tracks through the bitter dust that crusted her face, the corners of her mouth, the corners of her eyes.

“Kaalha be praised,” she murmured, falling against the damp sandstone in the shadow of the cave. Behind her, the hardpan across which they had just run blazed with light, impossibly brilliant. Too bright to look upon. Too bright even to look toward.

The cloth across Kaulas’s face was stuck wet to his skin. His breath made hissing sounds as he sucked air through it. And he was better off than Salamander and Maledysaunte, both of whom were crouched in the shade, hands on knees, gasping from the run.

“Polarizing filter?” said Prince Salih, wrinkling his brow.

Bijou fished it from her pocket. She pulled out a length of tight-woven beige cloth as well, draping it over her sunhat and her head as she edged around the shallow lake, back to the penumbra of the cavern’s welcoming shadow. She pinched the folds together around the lens, a cut of crystal magicked to protect her eyes even—she hoped—from the wrath of such a sun as this.

She wasn’t wasting time, she told herself. It would be a moment before the others had collected themselves enough to seek deeper in the cave.

Huddled in her makeshift blind, Bijou crept out into the light.

Even through the fabric, she could feel the heat instantly. It collected in the folds and scorched her fingers where she held the gather closed. But the suns—when she risked a quick glimpse—oh, the suns.

She had expected, perhaps, something like the suns of the veldt and the mountains—shining disks performing a stately courtship across the endless pale plane of the sky. But these were pinheads, negligible circles with an angular diameter no bigger than the sprocket-holes in a strip of silent-movie celluloid. The larger flamed a savage orange; the smaller burned actinic blue. It seemed as if only a diameter or two separated them, and a ceaseless tendril of flame curved across the space between to conjoin them. The fourth sun, as white and inoffensive as the nightsun, was a bright speck off to one side.

The heat was too much. Gasping in her shelter, Bijou ducked back inside the cave. How could that trifling thing drive her—already, after no more than a second or four—back into shelter, her skin prickling and sore where it had brushed the cloth? How could so much heat and brightness fall from so small—or so distant, more likely—a set of suns?

She groped for her water bottle and drank, swishing the water around inside her mouth so it would do the most good.

Back in safety, she folded cloth and lens and put them away. Her companions had gathered around Salamander, who crouched by the waterside. Bijou hoped they had remembered the warning not to drink. The dead stallion stood further down, sloshing water noisily with his skull as he tried to slake a thirst in flesh that no longer existed, but he was dead already: Bijou could not imagine the water would hold any terrors for him.

“That’s something,” she said, coming up to them. “Anyone else want to look?”

“Shhh,” Kaulas said without rancor. “Salamander has found a guide for us.”

Bijou looked down to see what the white Wizard held perched on her cocked forefinger. Orange as embers, and glowing softly in the shadows between a spatter of coal-black-dots…

“Of course,” Bijou said. “It’s a newt.”

“An eft, actually.” Salamander straightened up, licking her pinpricked finger again. Although it wasn’t her place to judge another’s magic, Bijou hoped there wasn’t too much newt slime on it. “She came this way.”

“The

n by all means,” said Prince Salih. “Lead us, my lady.”

Five

After the fire of the outside, the cavern with its echoing, plashing water was a cool relief. Kaulas convinced the horse-skeleton to stand rearguard, and they arrayed themselves and continued downward, along the shore of the underground lake.

Now they needed the torches—even the necromancers, once they passed around a curve or two and out of sight of the entrance’s reflected light. Bijou allowed the beam of hers to play out over the lake briefly, too entranced by curiosity to mind her own earlier cautions. The outer part of the cavern was raw and rough, wind-carved—but as they progressed backwards and it narrowed, they found themselves passing twisted filigrees of flowstone: stalactites, stalagmites, candelabras of stone that looked as if candles had melted and slumped down over them. The colors streaked and faded like the sandstone above, but this was something else—limestone, dissolved away and redeposited by millennia of water.

“We’re under a sea,” Bijou said suddenly, surprised. “A fossil sea. Limestone and sandstone.”

“Imagine,” said the prince. “This desert was water, once.”

The chime of Ambrosias’ zills halted abruptly. Bijou turned to track its jeweled gaze and saw something blunt-ended and swift coiling away among the twisted gardens of stone. Two bright spots in a light-banded black body caught the light of her torch before it vanished.

“Have a care,” she said. “I just saw an amphisbaena.” Then she realized that the guests might not have such things in their wet Northern lands. “A two-headed snake,” she explained. “Extremely poisonous.”

“And I,” announced Prince Salih, from further down the lakeshore, “just found Dr. Liebelos’s footprints. Or at least, the footprints of a woman with Northern boots, and not a ghul’s bare feet and claws.”

Salamander and the prince led them through caverns and chambers for what seemed a long time. This was a natural cavern system, but Bijou could see the marks of the chisel here and there where it had been retouched to make passage easier. Still they walked hunched over or sometimes crawled on hands and knees, drenched in the cold, cursed water, struggling to keep the electric torches dry. The sand in their boots grew wet and wore the skin in the crevices of their feet raw. Bijou worried about infection—and about the curse.

The floors were uneven, the flow of the stream in many places dammed up behind what looked like constructed terraces. Bijou knew they were the result of mineralized water evaporating and leaving a precipitate behind, but that didn’t change the wonder with which she observed them.

The caves were loud, resounding with running water and the footsteps of all of them. Confusing echoes fluttered all about. She wasn’t sure half the time if she was hearing the footsteps of her quarry, or her own, or those of her party.

Half an hour in, Kaulas muttered, “Who puts a forge in the bowels of the earth?” The tallest, he was obliged to proceed in a painful hunched shuffle. They’d given him the last position.

“The eft is confident,” Salamander said.

“And the footprints persist,” the prince said, pointing one out where it was smudged into a muddy patch.

Riordan said, “It seems logical to me that we are seeking no ordinary anvil, but rather one with a special connection to some underworld god. Perhaps they only used it in ceremonies, and those were carried out here.”

Bijou glanced at Maledysaunte. The necromancer’s face was mostly a pale blur in the gloom, but Bijou was sure it betrayed concern. Whatever Maledysaunte knew—whatever her Black Book told her—she kept it to herself.

Bijou’s eyes caught on a moving silhouette at the edge of the torchlight. “Halt!” she cried, her breath steaming in wet cold. Soaked clothes clung to her, and she shivered.

Everyone whirled, weapons ready.

But it wasn’t Dr. Liebelos. The shadow that detached itself from among shadows was the outline of a naked man. His head was shaved, his face clean-shaven. In the torchlight his skin shone glossy dark, browner than Bijou’s. Perhaps almost true-black—the red-black of a dark-hided horse, not the blue-black of Maledysaunte’s hair or a raven’s wing.

As he came closer, picking his way barefoot through the running water, the group of adventurers reflexively drew together. He didn’t raise his hand to shield his eyes from the beams of the torches. Bijou found herself staring at his face, unnerved by something about its structure or expression. She took an involuntary step back when she realized what it was: even the whites of his eyes did not shine—because his eyes had no whites. They were simply inky pools from lid to lid, and within them, she imagined she could see a faint shimmer like the schiller albedo of the huge, sooty moon that had so recently set.

“Don’t be afraid,” the man said. “I mean you no harm. It’s just been a long while since I saw your kind in the house of my ancestors.”

There was something about him—a neutrality of presence. Bijou quested after it with her wizard’s senses. He felt smooth and tepid to her mind. Plastic.

She was just figuring it out when Salamander said, “You’re not alive.”

“No,” Bijou said. “He’s a construct. An Artifice. Aren’t you?”

“Aren’t we all?” His tone was mild, amused. As sleek and room-temperature as the rest of him. Bijou noticed that even in the cave, it did not echo, though every other sound bounced eerily. “Whether we be made by gods or men is somewhat irrelevant.”

He paused at a distance of two canes or so and spread his hands. The mud and water of the underground river did not cling to him, but slid smoothly off his…surface. You couldn’t call something so poreless and frictionless a skin.

“What is your purpose?” Bijou asked.

“I am the guardian,” he said.

“Are you here to bar our way?” He wasn’t carrying any visible weapons, but that didn’t mean he couldn’t be one.

“I am an interpreter. I see to it that the will of the gods is recognized and understood.”

Maledysaunte stepped forward, angling her body to move between Riordan and Prince Salih. When she stood at Bijou’s shoulder, she squared herself and said, “What are you guardian of?”

The blackness of his eyes made it impossible to see where he was looking. “I know your voice,” he said. “It was your voice that awakened me. You spoke words in the true tongue. You are the Book.”

“I am,” she said. “I seek the one who would destroy me. Will you let me pass?”

“I will,” he said in his echoless voice. “And I will come with you, where you go.”

Bijou put her hand on Maledysaunte’s sleeve, drew the necromancer close so she could speak into her ear. “You don’t trust that.”

“You can’t trust that,” Kaulas interposed.

Prince Salih merely stood quietly, one hand upon the hilt of his scimitar, and watched them all with a gentle frown.

Maledysaunte drew back enough to smile at her. “I trust nothing,” she said. “But he’s in the Book.”

Now they were seven, though the guardian’s presence was not like a presence at all. A hush settled over them with his arrival, so even the splash of footsteps in cold water seemed curiously muffled. They crept in the light of Bijou’s one dim torch until their eyes adapted—that is, the eyes that needed to adapt. For a long while, they did not speak; they only descended.

Salamander crept at the front with her newt and Prince Salih; Bijou walked just behind them.

The long silence was broken when Salamander said, in a whisper that nevertheless echoed, “You must think me an unnatural monster, who would hunt her own mother.”

Bijou let the back of her hand—the one that didn’t steady the torch—brush Salamander’s arm—the one that was not bent up to support the newt. The white Wizard’s words fell into Bijou’s heart—a lump of old pain like a stone in a still pool. And a mother who would not protect her own child? What kind of a monster is that?

But the betrayals of Bijou’s childhood were not Salamand

er’s concern. Not yet, anyway. If this fragile connection between them ever blossomed into friendship, though—

Bijou began to think she might someday mention it.

“I think a courageous—a loyal—child protects her mother,” she said, when she could get the words around the ache in her bosom. “That’s why you’re here, isn’t it?”

“My mother,” Salamander said. And, with a glance over her shoulder to Maledysaunte: “And my friend.”

“Well then.” Bijou nodded, as if that explained—and absolved—everything.

Perhaps it did.

Salamander turned her hand around and grasped Bijou’s fingers. She didn’t say thank you. It wasn’t required.

Salamander squeezed. Bijou was still holding her hand when the river began to glow with a warm, amber light.

Salamander lurched forward without hesitation, dragging Bijou along with her for a couple of steps until they dropped hands. Salamander still held the hand with the newt balanced on it high and as steady as she could. “Run—”

Three steps, no more, with the feet of their allies pounding the sand and stone behind—and Bijou fetched up hard against a shimmering curtain of light that nevertheless felt hard and slick as a mountain of glass.

“Trap,” she said. She turned her back to it to survey the rest of the group.

The amber light englobed them completely. It crept across the uneven floor underfoot; it gleamed among the stalactites overhead, giving them an appearance of melted wax limned by candlelight. Sourceless, shadowless, it glowed steady and sure, even and bright, and did not flicker in the slightest. Its directionless shine flattened surfaces and washed out detail, making everything appear thin and papery.

“Amber,” Kaulas said on Bijou’s other side. “There’s a symbolism—”

“Amber,” Salamander agreed. “She’s a precisian. What do you think it means?”

“Trapped in amber,” Maledysaunte said. “Sealed away forevermore.”

“Well,” said Riordan dryly, “she wouldn’t want to kill her daughter if she could avoid it.”

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

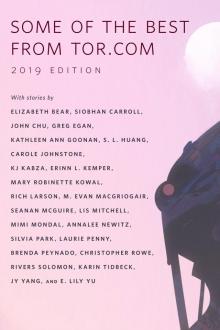

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3