- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Page 4

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Read online

Page 4

Then there was the glory of painting. The splendor, the fascination—the recognition! Praise temporarily chased away her anger. Lisane sought accolades from patrons, esteem from peers, devotion from admirers. Nothing salved her better than the adulation of her student lovers whose kisses mingled awe and desire. She left them smoldering as she passed from one to the next, always seeking new, white-hot passions.

The figure in the bed had become even more frail now. Her bulbous head loomed above her withered torso, dominated by bloodshot eyes and cavernous mouth.

“Keep painting!” Rage hissed through Lisane’s teeth. The painting had stripped her façade, leaving nothing but furious ambition.

There were things I had to know.

“Why did you teach me magic before I knew how to paint?”

She loosed a feral snarl.

“The usual techniques weren’t working,” she said. “I had to innovate, to use a different tool.”

I’d known the answer, but to hear it—I simmered with bitterness. “You ruined me.”

She jabbed a desiccated finger toward the canvas. “If I hadn’t dared to risk breaking you, you’d never have made that! You’d be some ordinary Orla, preparing to take my house and leave a legacy of mediocrity. You’re my true heir. The only one who was worth my time.”

“If I’m your heir, then give me the house.”

“What would you do with it? Paint miserable nothings? Paint the dying until someone turned you in and they dragged you through the streets? You’re the last of my line. In a hundred years, when there’s no one left to be punished, my estate will bring out the painting. Then they’ll see. They’ll see what you did. They’ll see what I made you.”

Her teeth shone with saliva. Her fingers clutched the air.

I wanted to flee. I wanted to kill her. I did the latter. I did it with paint.

Lisane didn’t even say she didn’t want me anymore. She just barred her door and told the cook’s son to keep me out.

Despite his crippled left foot, the cook’s son was enormous—the size of the duke’s dancing bears. Not that he needed much strength to deter me, fourteen years old and still the size of a younger child.

I flailed against him. “I always come in the evening. That’s what I do! Ask her! She’ll tell you to let me in! She’ll tell you—”

By now an expert in detaining Lisane’s rejected lovers, Colu caught my fists as I tried to pound his chest. He let me thrash until I began to cry and then he led me quietly downstairs. I expected him to return me to the apprentices’ quarters, but instead he took me to the kitchen and sat me before the foul mouth of the oven.

He brought me a stale sweet from the previous day. I nibbled on its edges, devoid of appetite. “It’s what she does,” he said. “Nothing to do with you.” Sotto voce, he added, “Best forget it.”

I should have listened.

Instead, I waited until evening when Lisane met with the journeymen to discuss the apprentices’ work. The other apprentices were doing chores or snatching a few moments to sit outside with a crust from supper, enjoying the last of the night. I lingered in the shadows behind the archway until I couldn’t bear it anymore.

I threw myself at her skirts. The journeymen drew back, laughing nervously. “Renn!” Orla exclaimed, reaching to pull me away. I ignored the plump fingers stretching toward me.

“It's a mistake!” I shouted. “Tell Colu you didn’t mean it. I don’t know what I did, but I won’t do it again. Please! Let me come back. I’ll get better at painting, I promise. I’ll do whatever you want.”

I still remember the look of disgust on her face as she pried me away from her skirts.

Even then, I could have left. Instead, I ran to the bench beneath the window and began smashing the dye pots.

Someone moved to restrain me but Lisane held up her hand to stop him. “Let the creature tire itself.”

I ran back to the easels and toppled them, one by one. Half-painted panels clattered across the floor. I cracked one against the wall. Wood splintered. I reached for a second. Finally, Lisane decided she’d had enough.

“Where is this one’s work?” she demanded.

Orla was crouching by the wall, her hands thrown over her face like a painted mourner. I thought she was ashamed of me, but now I wonder if she wasn’t feeling a deeper shame. What similar scenes might played out before I entered the house?

Slowly, she lowered her hands and raised her eyes. “In there, mistress,” she said, gesturing vaguely to the heap of panels.

“Locate it,” said Lisane. “Now, please.”

Laboriously, as if pushing herself through an invisible substance, Orla went to the middle of the room and dug through the pile until she found my most recent effort. She laid it carefully on the floor.

Lisane gave it a brief, disgusted glance. “This one’s work is not improving.”

Her gaze moved from the painting up to me, her expression displaying utter loathing. She shook her head and swept out of the room, leaving others to straighten the mess.

Orla began picking up the panels. One by one, the other journeymen stooped to help. A sweet-smelling dusk breeze blew through the open shutters, ruffling their sleeves. It was dim and the shadows were gathering.

Angry oranges now, bright and uncompromising, jagging down the canvas like lightning bolts. Snarls of unflinching, determined white, tangling in the corners and then stretching into tendrils, writhing blindly toward something neither they nor I could reach.

When I finished at last, I steeled my nerve to turn back to the bed. Lisane was gone—not a husk, not an ash, not a trace. Only her rumpled sheets remained beneath her enormous headboard.

Whatever had happened to her soul, it was finished now.

I stood shaking by her empty bed for a long time, wondering if I was mad. I did not feel mad, but I did feel different: a trifle colder, a trifle more resolute.

The angle of the sun’s rays shifted through the shutters, creeping toward me across the floor. Eventually, Orla came up the stairs. She lingered in the doorway, holding a lit candle even though it was daytime, her head bowed as if she was afraid to see what I’d done.

Age had stolen the peachy smoothness from my rival’s skin, but she’d gotten heavier instead of lining so she still looked young. Wrapped around the candle, her short fingers were rough, her knuckles knotted. Stained fingertips testified that she continued to paint even though many teachers became indolent once they had students.

She braced in the doorway, ready to defend herself. “I wasn’t sure if it was over,” she said, glancing at the empty bed for a moment before looking hastily away.

I wanted to berate her for standing in front of me, acting as if we were equals when Lisane had given her the house, had given her everything. Instead, I snapped, “There are no ghosts here.”

“Of course not,” she said, looking guiltily at the lit candle. Cautiously, she set it on Lisane’s bedside table before snuffing it out. “You’re not—” she began. “You don't seem—”

“I’m not mad.”

She peered shrewdly at my face. “No,” she said eventually. “You don't seem to be.”

“Did Lisane tell you I would be?”

“She said to be careful. She knew she was taking a risk.”

“You mean I was taking a risk.”

She nodded.

“Lisane thought you might have enough magic to protect you…” Orla said.

I shook my head. “It wasn’t the magic.”

Orla raised her brows. “No? Then what?”

I tried to imagine what it would have been like to paint a stranger, to be overwhelmed with all their unfamiliar memories and desires. I’d had a lifetime of bending myself around Lisane’s passions.

I didn’t want to discuss it with Orla. I gestured at the portrait to distract her. “It’s done.”

Orla had been avoiding the canvas until I called her attention to it. Now, at last, she turned.

A tremor ra

n through her body. She stepped carefully forward, approaching with a mixture of reverence and fear. She reached out to touch the surface and then pulled her hand back as if it were radiating heat.

“It…” she said. “I don’t know what it is. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“It’s Lisane.”

“It looks…determined. Passionate. Angry.”

“It’s Lisane.”

She moved even closer, angling her head as if preparing for a kiss. The expression on her face was beatific. Wisps of hair fell loose from her cap and the morning light seemed to make her features glow. She reached out again. This time her fingers skimmed a white tendril.

As I watched Orla’s rapture, a sudden realization struck me. I no longer loved Lisane. Something had changed during the day and nights I’d spent painting. The expression on Orla’s face was familiar, but also foreign, a memory of something past.

Orla shook herself like a bird after a bath. She turned from the canvas. “We need to take it down to the cellars. Lisane left instructions. The journeymen are preparing. I’ll let them know it’s ready.”

“Must you?” I murmured despite myself.

She blinked at me as though I’d gone mad after all. “What else would we do?”

My gaze slanted away. “I'm being foolish.”

“No,” Orla said, almost sighing as she looked longingly over her shoulder. “Anyone would want to display it. It’s astonishing, Renn.” Her voice was quiet, but hard with pain. “She said it would be.”

Lisane, oh my Lisane. You spent your life making me. Then I spent my heart remaking you.

After the disaster in the studio, I never begged you to take me back again—but I still followed you when I could, hiding in the shadows so you wouldn’t know I was there. I watched you instruct the other students, and in those moments when your fingers inevitably intersected theirs, I imagined their coolness brushing mine. I reveled in your lingering scent. You smelled more like paint than flesh, but wasn’t that the way it should have been? You always cared more about art than bodies.

All of us watched you from the shadows. Orla and Giatro and Xello and Rey and Cosiata, back to the first. The painting of our lives shows you striding forth brilliantly into the light while the rest of us crouch in your wake, hastily sketched into the background by an artist late on his commission.

I watched from the top of the stairs while they prepared to take the portrait down to the cellars where it would bide until all of us were dead. A journeyman covered the wet canvas with a protective cloth. Another, holding a lit oil lamp aloft, led the way out. Orla followed, cradling the wrapped painting like an unwieldy child. Others trailed behind, solemn as a funeral procession.

Giatro was the last to go. He lingered in the lee of the doorway, watching the others. Even from a distance, I could see he hadn’t slept. His eyes were hollow and dark, smudged beneath with a color like ash. Without thinking, I saw him as a composition of shapes and colors: the oval of his head bowed toward the shaking rectangle of his chest, his newly shorn hair dark against his pale scalp.

He wept alone in the shadows for a few moments before departing.

When the hall was empty, I descended the stairs. I crossed away from the basement, my footsteps heavy on the russet tile, and pushed open the heavy oak door that guarded the manor from the street. The morning was overcast, the foliage deep emerald against the white. Complex shadows folded beneath the shrubbery, changing shape as the wind tousled the leaves. The sundial’s shadow fell, arrowlike, across stone and herringbone brick, pointing toward an early hour.

I could never paint anyone else into canvas, never make another masterpiece. I would always be surrounded by tools I could never master while being forbidden to use the one I could. I’d return to my cold studio to spend my life painting pedestrian landscapes for clients who wished they could afford better artists.

And yet, I’d gained something, too. I’d spent my life trying to please Lisane. Now I was finally free to move out of her shadow.

I trudged across the meandering pathways, enclosed by the heavy scents of late-blooming flowers and the whistle of lonely birds. Overhead, the clouds blew into new formations of grey and white. My hand lingered on the latch for a moment before I opened the gate and left Lisane behind.

Copyright (C) 2012 by Rachel Swirsky

Art copyright (C) 2012 by Sam Weber

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Begin Reading

The wild griffins for which the region was famous were sporting in the sky above the snow-clad peaks of the Riphean Mountains when Sir Toby arrived at Schloss Greiffenhorst, late as usual. The moot had been in session for three days and, truth be told, no one had noticed his absence until his carriage clattered into the courtyard. Then there was such a to-do, with horses ramping and snorting white plumes of steam and footmen unloading brass-bound trunks and the building-master of the conference center shouting and turning red as he tried to wave the luggage around to the back of the building, that the English lord’s emergence came as a distinct anticlimax.

But then Sir Toby, tremendous of girth, smiling widely at the imagined warmth of his reception, and carrying a small kettle-dragon in a cage against the possibility that he might suddenly need to warm his feet, stepped out of the carriage and onto a patch of ice.

He went flying.

Junior Lieutenant Franz-Karl Ritter had just stepped outside, his wolf Geri padding along at his heel, to enjoy a cheroot in the winter air. He was shaking out his lucifer match when he saw this whimsical mountain of flesh hurtling toward him.

Bodies collided. Ritter’s cigar went flying from his mouth, tracing a perfect arc of smoke behind it, and he found himself, half-dazed, lying on the ground. Then he was being helped to his feet by the same man who had knocked him down.

There was barely enough time for Ritter to note with satisfaction that, though Geri stood bristling and fangs bared, he had, as per his training, refrained from attack. Then Sir Toby slapped Ritter’s back so hard he almost went down again. “Gallantly done, young fellow! Thank you for cushioning my fall. I doubt it was exactly deliberate, but at my age one does not look too skeptically at a kind deed.” He thrust out a hand. “Tobias Gracchus Willoughby-Quirke, at your service. British born—as I’m sure you can tell by looking—but now a wandering magician-at-large. And you are—?”

“Kapitänleutnant Franz-Karl Ritter. Werewolf Corps. I’m responsible for security here.” They shook.

“Excellent, excellent! You can help my people set up the demonstration. That way you will be assured of a good position from which to observe it.” Sir Toby turned away, saw somebody he knew, and with a happy bellow of greeting, plunged inside. In his wake, Ritter saw four footmen carrying a trunk shoulder-high as solemnly as pallbearers with a coffin.

Quickly stepping in front of the servants, Ritter shook a finger at them and said, “Stay.” Then he hurried after the English maniac.

At the door, however, the Margrave von und zu Venusberg stopped him with an upraised hand. “Let them by, nephew,” the margrave said. “Sir Toby must have his little show.” He gestured the footmen to come within. “You may set up in the billiards room,” he told them. “Up the stairs, down the hall on the right, third door to the left.” Then, returning to Ritter, “You’ve never seen this. I believe you’ll find it diverting.”

“Shouldn’t I be…?”

The margrave

raised his eyebrows and pursed his lips in a way that was clearly meant to look wise. “This is the largest conclave of wizards in Europe in over a decade and I pulled a lot of strings to bring you here. There are people to meet and connections to be made. Your parents would not be pleased if you wasted this opportunity by playing soldier.”

“No, uncle.”

Guests were already gathering in the billiards room when they arrived, and, contrary to Sir Toby’s peremptory command, the footmen required no help whatsoever setting up. They carefully placed the trunk down atop a billiard table and then unlatched one side. It swung upward, revealing a set of small, well-appointed rooms such as might constitute a child’s dollhouse if only said child were both wealthy and fixated upon military housing. There were tidy officers’ quarters, barracks filled with bunk beds for the enlisted men, two separate messes, lounges and game rooms, and a kitchen with tiny copper pots and pans a-gleam.

Out marched a platoon of miniature musketeers, no more than two inches tall.

Diminutive pipers piped and wee drums rumbled. All but unnoticed, the servants latched up the trunk and whisked it away, while the soldiers formed up in two lines on the green baize.

“Parade, atten-shun!” Sir Toby commanded.

The soldiers snapped to attention.

“For this demonstration, my men will be firing powder without shot,” Sir Toby remarked. “Just for safety, you understand.” Then he barked, “First section, prime and—load!”

The front line brought their muskets to the priming position, pans open. They drew cartridges, bit off the tops, and poured a pinch of powder into the priming pans and the rest down the barrels. Then they drew ramrods and drove paper wadding down the barrels, tamped twice, and returned their ramrods to the hoops under the barrels of their guns. It was all done in perfect unison.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

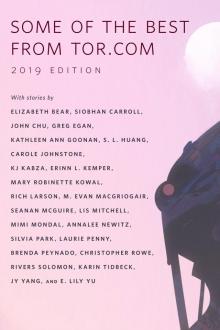

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

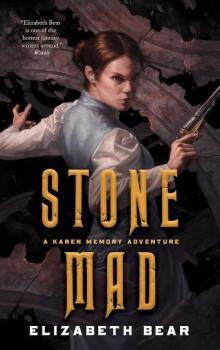

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

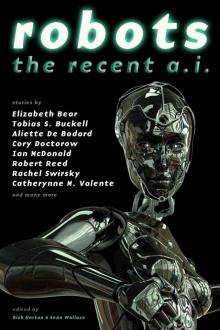

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3