- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Page 5

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Read online

Page 5

“Second section, prime and load! First section, present arms! Fire!”

Ritter watched, entranced, as the back line loaded their muskets and the front line fired a crisp fusillade.

“There are ten steps involved in loading and firing, but the commands I have given are those which, for efficiency’s sake, would be employed in actual combat. Now my men shall demonstrate skirmish formation. Second rank, advance and—fire!”

The rear line of soldiers stepped through the spaces between the men before them, put muskets to shoulders, and fired. Behind them, what had been the front line was reloading.

“British soldiers can routinely fire three shots per minute,” Sir Toby said. “In this formation, that amounts to one shot every ten seconds. Formidable indeed! Firing in rapid succession rather than simultaneously, my men can lay down a wall of bullets while advancing steadily across the battlefield. Now let us see what happens with a formation of three ranks. You will note that…”

Ritter found himself mesmerized by the beauty of Sir Toby’s innovation. Utilizing such a toy militia, a military theorist could design and test new formations with a minimum of expense and no danger to actual soldiers. Here, before him, were the beginnings of a true science of war—one whose findings would be testable, verifiable, and reproducible. He wondered if Sir Toby was aware of its possibilities. This could modernize warfare, ushering it into a new and more efficient era!

Ritter was awakened from his speculations by polite applause marking the end of the show. Sir Toby beamed as if the accolades had been thunderous. “Thank you! Thank you! What you have just seen was but my little party trick. Now, however, comes my pièce de résistance!” At a gesture one of his footmen solemnly knelt and pried open a baseboard with a silver wedge. The miniature soldiers, meanwhile, had affixed weapons and instruments to their backs and were rappelling down from the billiards table on ropes no thicker than threads. They formed up again on the oriental carpet. “When people ask me why I am welcome, as so few are, in all the great houses of Europe, I always reply: Because after the display of close order drill, I send my men into the underbelly of my host’s house to systematically hunt down and kill all the rats and mice, leaving it literally vermin-free. This house gift, if you will, is why, for all my faults, I am universally beloved.”

Nodding downward, Sir Toby said, “Sound the charge.”

A tiny figure lifted bugle to lips, producing a sound as faint and distant as the horns of Elfland. With a cheer, the soldiers charged into the wainscoting and disappeared.

Ritter’s jaw fell. He managed to hold his peace until the room was nearly empty and then, turning to his uncle, murmured, “Did you take note of exactly how many of Sir Toby’s toys went into the wall?”

“No, of course not. I doubt if anybody did.”

“Exactly! And if nobody’s counted, who is to say that the number of men who come out of the walls is the same as the number who went in?”

An amused tone entered the margrave’s voice. “Are you suggesting that Sir Toby is a spy?”

“I’m just saying that it’s the sort of thing we should be keeping an eye on.”

“Come outside with me.”

Ritter followed his uncle on to the balcony. The margrave seized the railing with both hands and stared into the distance. “Have you ever wondered how it is that the ability to work magic is largely concentrated in the nobility?”

“I had always assumed that ability was responsible for their ascension in the first place.”

“Possibly. Yes, that is the story we tell. Yet it could easily have gone the other way, with the common ruck of men reacting with fear and loathing rather than awe and respect. We would then be an impoverished, persecuted minority—untrained, unable to develop our powers, and slowly dwindling toward extinction. Sometimes I wonder if it wouldn’t be better that way.”

“Uncle!”

“You see that dead tree on the mountain slope across the valley?” Ritter did, though it was little more than a brown smear in the distance. “Watch it carefully. Count to three under your breath.”

Ritter did so. One…two…

The tree flashed into flame.

“Impressive, you might think. A cannon could do as much! Yet because I was born with the aptitude and my parents insisted I put in the years of hard work required to develop it, I am entrusted with some share of responsibility for the fate of my nation.”

Ritter nodded, wondering where all this was going.

His uncle turned his back on the mountain. “Magic is a very poor basis for power. You must learn to excel in politics if our house is to survive. Most of the great families nowadays do not realize this, which is why they are led by mutton-headed fools, suited only for small wars and wizard-feuds. Weak as watered milk, the lot of them! And Sir Toby is the worst of all. When he was young, some predicted that he would someday become one of the preeminent wizards on the continent. Yet what has he done with all his potential? Nothing, God help us, but play with toy soldiers!”

“I see,” Ritter said. Privately, though, he wondered. Exactly how clever were Sir Toby’s automata? Could he possibly see through their eyes and hear through their ears? Sir Toby might not be the fool he presented himself as being.

He knew better than to say so to his uncle. But it was worth keeping in mind.

Most of the conference’s work was done in closeted meetings, both large and small, to which Ritter was not privy. But judging by the informal conversations he overheard, Ritter didn’t think that much was being accomplished behind those closed and guarded doors.

“I am sick of hearing about the Mongolian Wizard!” Madame de Lafontaine exclaimed at the cocktail party at the end of the day’s session. “Why are we so afraid of this scarecrow? Five years ago, nobody had even heard of him.”

“Yet now he controls all of Russia,” Count Gasiewski said. “Do you not find that alarming?”

“Anyone can conquer Russia. I could do it myself. But I should like to see this upstart try to conquer France.”

“So would I, were my nation not situated between the two of you.”

The Frenchwoman ignored the jibe. “Anyway, how could even one tenth of the powers ascribed to him be true? It would take centuries to develop them.”

“Some say he is a thousand years old,” the Swedish general Tino Järvenpää said. “Others that he is immortal. Having faced down his forces at Ladoga Karelia, I am prepared to believe anything, and reluctant to provoke him a second time.”

Standing with his uncle, listening respectfully, Ritter happened to glance at the far end of the room, where Sir Toby had been holding forth on the tactics of close order drill, and saw the Englishman take a step backwards from a knot of conversation which had clearly moved beyond his signature obsession—and disappear.

Ritter blinked.

But the margrave chose that moment to squeeze his arm and comment warmly, “Madame de Lafontaine is quite a striking woman, isn’t she?” Which, indeed, was so. Half the men in the room were drawn to her as flies to a ripe apricot.

“She is as beautiful as springtime.” Why would a man draw attention to himself by his boorish conversation and then literally disappear? Because he wanted everyone to recall that he was present long after he departed. Surely there were innocent reasons for such an action, but other than an assignation with a married woman, Ritter could not think of any. And Sir Toby did not strike him as the womanizing type.

“She is in her late fifties,” the margrave said.

“Eh?”

“Her power is glamour and her weakness is vanity. So she employs it in order to appear forever young. A politically negligible creature, but talented in the boudoir.”

“You speak from experience?” Ritter would have liked to follow Sir Toby and find out what the scoundrel was up to. But he knew his uncle would not tolerate it.

“From many experiences. We once spent a week in Trieste which…Well! I think that it would be well worth my time

to rekindle our acquaintance.” He winked in a confidential manner. “Watch and learn how a man of experience handles such a woman.”

Madame de Lafontaine had just produced a cigarette from a jeweled clutch. So the margrave strode forward, a flame dancing atop an outstretched finger, to light it. “My darling Gabrielle!” he said. “How delightful to see you again.”

Madame de Lafontaine’s face froze. Then she turned her back on him.

Somebody gasped. A gentleman or two raised a handkerchief to his mouth to help stifle involuntary laughter. Whispers spread through the room as those who had witnessed the event described it to those who had not: The Margrave von und zu Venusberg had been snubbed, by God! Cut dead and in public too.

The margrave flushed furiously and, turning on his heel, fled the room.

In the wake of his mentor’s departure, Ritter led his wolf out of the Great Hall, pausing now and again for a brief pleasantry (for he was not entirely deaf to his uncle’s teachings) with a dignitary whose acquaintance he had already made. In the vestibule, he slid into Geri’s mind, expertly soothing the animal’s natural resistance to the invasion. Then he visualized Sir Toby. The wolf’s mind immediately called up a scent compounded of human sweat, pipe tobacco, dark beer, Italian boot leather, gunpowder, and India ink. Follow, Ritter commanded. Find.

Wolf first, they moved all but noiselessly out of the public areas of the conference center and into the warren of narrow corridors employed by the servants. When Geri started to turn into the kitchen, Ritter laughed and yanked back on his mental leash. “No, no, greedy-guts. I shudder to think what a fuss the chef would make if I let a carnivore like you into his demesne!” He doubted that Sir Toby would have been looking for a snack when there were servants with trays of canapés working the reception. So he must have been merely passing through. Patience, Ritter thought, and led the wolf out a side door and around the back of the kitchen.

Picking up the trail again, Geri led them to the rear of the conference center. There a large pair of doors opened on to a set of stone stairs leading down into the storage cellar. The soldier Ritter had set there on guard saluted at his approach.

“Did anyone go into the basement just now?”

“No one, sir!”

“You are positive?”

“Yes, sir!”

Through the wolf’s sensorium, Ritter could taste Sir Toby’s scent, mere minutes old, leading downward. Without another word, he plunged down the stairs.

The storage rooms were all but lightless. But Ritter did not strike a match, trusting instead to his animal’s night vision. Stealthily, they moved through labyrinthine passages, always following the Englishman’s trace, until finally they saw the glow of a candle in the darkness and then the corpulent outline of Sir Toby. He was frantically shoving luggage to one side and another on the shelves.

Ritter coughed to announce himself.

Sir Toby spun around, holding the candle high in one hand and simultaneously thrusting the other into a jacket pocket. Then, upon his recognizing Ritter, the hand emerged empty.

“Junior Lieutenant Ritter!” Sir Toby exclaimed. “I am extremely glad to see you.” In his voice was not the least trace of the jovial buffoon he had earlier presented himself as being.

“I hope that is true,” Ritter said. “For I am alarmed to see you in such incriminating circumstances, Sir Toby. Tell me exactly what you are doing here, sir—and do not think to use your disappearing trick on me. A wolf’s senses are not so limited as a man’s.” He kept a light hand on Geri’s mental leash, prepared to launch him at the Englishman at the first sign of aggression.

But Sir Toby showed none. “I am searching for my men. Forty went into the wainscoting and not a one has come out. Something terrible has happened here in the darkness and I fear it was a massacre.”

“A massacre…of toy soldiers?”

“They are not toys,” Sir Toby said grimly, “but living, thinking men like you and me. Those you saw are mercenaries from a recently-discovered island nation in the Pacific Ocean. They—” Sir Toby paused. “It would help if I knew how much you already know.”

“I know that you are in a very suspicious position and I am all but certain that you are a spy—for whom I cannot say. Allow me to assure you that the diplomatic immunity you enjoy upstairs will not of necessity protect you here, where there are no witnesses.”

“You are a hard and suspicious man, kapitänleutnant, and I wish I had a dozen like you working for me. Yes, I am a spy, in the service of His Majesty King Oberon VII, and, yes, I was placing agents in the building to determine the disposition of the various powers represented here. Your nation and mine both recognize the threat posed by the Mongolian Wizard and thus it is but prudent for us to do all we can to promote an alliance of the great houses of Europe. I make no apologies for a deed that requires none.”

Geri made a low noise in the back of his throat. Careful to keep his outward attention focused on the English spy, Ritter followed the wolf’s thoughts and then said, “It seems that at least part of your story is true. My partner scents small corpses—many of them—two rooms further in.”

When Sir Toby saw the tiny bodies scattered about the floor, he hurried to them and, kneeling, searched anxiously for any sign of life. “Dead, all of them!” he moaned. “Yet there’s not a mark on anyone. What can have caused this horror?”

Meanwhile, Ritter followed a foul stench to the foot of a crate that had been broken open and, among its splintered slats, found something that looked like the bedraggled corpse of a rooster tangled up with a dead adder. He nudged the thing over with his toe, and lit a match so he could examine it. His blood ran cold.

It was a basilisk.

“I’ve found the cause of the massacre,” he said. “Dead, thank God.”

Sir Toby brought his candle close. “Its breast is riddled with bullet-holes. Dying though they were from its poison, my men brought the monster down.” He wiped a tear from his eye. Then, “The basilisk is a desert creature. How in the world did one wind up here?”

“They released it. For some reason they broke into this crate and it was waiting inside.” Ritter put his hands into the breach and began pulling slats free. Most of the crate’s interior was empty—living space for the guardian basilisk, obviously—but at its center was a smaller box, perhaps three feet across, made of teak. Its surface was richly carved in geometric patterns and stylized flames. He lifted the lid and the scents of cinnamon, spikenard, and myrrh wafted forth. Inside the box, nestled among dried spices, was something smooth and golden and round.

It glowed in the darkness.

Sir Toby grabbed Ritter from behind and pulled him away from the thing. “Don’t touch it!” he cried. “It’s a thousand times more lethal than the basilisk ever was.”

“What is it?” Ritter said wonderingly.

“A phoenix egg.”

The conferees did not much like being evacuated, of course. But Ritter knew his authority and was prepared to act on it. He set one of his men to hammering on the alarm gong and others to emptying out the Schloss floor by floor. “Don’t be afraid to shoot anyone who disobeys you,” he said, knowing that a soldier with such orders would present himself in such a way as to make the action unnecessary. To the building-master, he said, “Have the ostlers get the horses into harness and line up every carriage you have out front. Lords and wizards go first, naturally, but I want every human being down to the meanest servant out of here by midnight.”

“But where will they go?” the man demanded.

Ritter glanced at Sir Toby. “The village at the foot of the mountain ought to be far enough,” the wizard said.

“Send them to Plattergarten. We can requisition space for them when we get there. Nobody is to wait on luggage or to take more than they can easily carry. When you run out of carriages, send people down the road on foot. My soldiers will go last and rest assured they will not be easy on anyone who tries to stay.” A distressed nobleman came runn

ing up and he turned to face the man. “Yes, uncle?”

“What madness is this? You are making enemies of half the wizards on the continent!”

“Better that they should hate me than that they should die.” Ritter crooked a finger and one of his men stepped forward. “See the margrave to his carriage and make certain that his is the first to leave.”

When the margrave had been led away, Ritter murmured, “Do you think we can get all of them safely away?”

“Somebody brought the phoenix egg here, and that someone can only have been one of the visiting wizards. Whoever it was, you may be sure, is high in the Mongolian Wizard’s trust. He would not be somebody to be lightly discarded. Yet all the delegates are still on the mountain. That, and the tradition that says that the phoenix is invariably reborn at dawn, tell me we have time enough and some to spare.”

“Very good,” Ritter said. “Things seem to be well underway here. Let’s see if we can catch our saboteur.”

It was twilight by the time the first carriage rumbled down the mountain. Standing at the gatehouse by the entrance to the grounds, Ritter saw his uncle’s face, white and disapproving as a ghost’s, through its window. “I hope I have not just disinherited myself,” he remarked. Though, in fact, the prospect did not bother him one whit. He was now convinced that war was coming, and in time of war there was always work for a soldier.

“I, meanwhile, hope that your furry friend is as good as you say.” Sir Toby stood, hands in pockets, scowling, with his greatcoat flapping slightly in the chill breeze.

“Cinnamon, spikenard, and myrrh are distinctive odors. Geri sensed the combination more than once over the past three days, but I thought it merely a whiff of perfume worn by one of the ladies. Our saboteur has traces of those spices on his hands and does not know it. We shall sniff him out, never fear.”

One by one, the carriages paused at the gatehouse, then trundled down the road from Schloss Greiffenhorst and disappeared into darkness. Ritter stamped his feet and blew on his hands to keep warm. Occasionally a runner came, bearing news or requesting instructions. But Geri, though he dutifully sniffed at each conveyance, discovered nothing.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

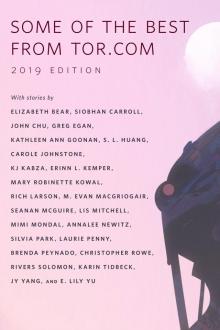

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3