- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

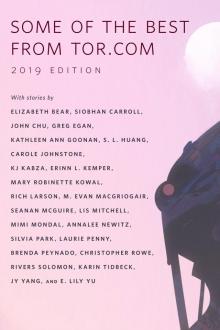

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Page 4

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Read online

Page 4

I guess she and Robin were both doing what they thought was best for me. Funny how none of us seem to have a consistent idea of what that is.

I don’t read the legalese. I start to laugh.

I can’t stop.

I unlock the car. I toss the phone on the floor and lock it again. Then I walk away on sore feet, alternately chuckling to myself and sniffing tears.

I pick a flatter trail this time, and half a mile along it I start wondering about a complicated function I was working on before I went on leave, and whether that one student got their financial aid sorted out.

No matter what choice you make, you’re going to regret it sometime. But maybe not permanently. And it wasn’t like I had to decide right now. I had the day off. Nobody was looking for me.

It was going to be a hot one. And I still had some walking to do.

About the Author

Elizabeth Bear was the recipient of the John W. Campbell Award for Best New Writer in 2005. She has won two Hugo Awards for her short fiction, a Sturgeon Award, and the Locus Award for Best First Novel. Her novels include Karen Memory and The Eternal Sky Trilogy. Bear lives in Brookfield, Massachusetts.

Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Bear

Art copyright © 2019 by Mary Haasdyk

For He Can Creep

Siobhan Carroll

A Tom Doherty Associates Book

New York

Flash and fire! Bristle and spit! The great Jeoffry ascends the madhouse stairs, his orange fur on end, his yellow eyes narrowed!

On the third floor the imps cease their gamboling. Is this the time they stay and fight? One imp, bolder than the others, flattens himself against the flagstones. He swells himself with nightmares, growing huge. His teeth shine like the sword of an executioner, and his eyes are the colors of spilled whale oil before a match is struck. In their cells, the filthy inmates shrink away from his immensity, wailing.

But Jeoffry does not shrink. He rushes up the last few stairs like the Deluge of God, and his claws are sharp! The imps run screaming, flitting into folds of space only angels and devils can penetrate.

In the hallway, Jeoffry cleans the smoking blood off his claws. Some of the humans whisper their thanks to him; some even dare to stroke his fur through the bars. Sometimes Jeoffry accepts this praise and sometimes he is bored by it. Today, annoyed by the imps’ vain show of defiance, he leaves his scent on every door. This cell is his, and this one. The whole asylum is his, and let no demon forget it! For he is the Cat Jeoffry, and no demon can stand against him.

* * *

On the second floor, above the garden, the poet is trying to write. He has no paper, and no pens—such things are forbidden, after his last episode—and so he scratches out some words in blood on the brick wall. Silly man. Jeoffry meows at him. It is time to pay attention to Jeoffry!

The man remembers his place. Reluctantly, painfully, he detaches his tattered mind from the hard hook-pins of word and meter. He rolls away from his madness and strokes the purring, winding cat.

Hail and well met, Jeoffry. Have you been fighting again? Such a bold gentleman you are. Such a pretty fellow. Who’s a good cat?

Jeoffry knows he is a good cat, and a bold gentleman, and a pretty fellow. He tells the poet as much, pushing his head repeatedly at the man’s hands, which smell unpleasantly of blood. The demons have been at him again. A cat cannot be everywhere at once, and so, while Jeoffry was battling the imps on the third floor, one of the larger dark angels has been whispering in the poet’s ear, its claws scorching the bedspread.

Jeoffry feels … not guilty exactly, but annoyed. The poet is his human. Yet, of all the humans, the demons seem to like the poet the best, perhaps because he is not theirs yet, or perhaps because they are interested—as so many visitors seem to be—in the man’s poetry.

Jeoffry does not see the point of poems. Music he can appreciate as a human form of yowling. Poems, though. From time to time visitors come to the madhouse and speak to the poet of translations and Psalms and ninety-nine-year publishing contracts. At such times, the poet smells of sweat and fear. Sometimes he rants at the men, sometimes curls up into a ball. Once, one of the men even stepped on Jeoffry’s tail—unforgivable! Since then Jeoffry had made a point of hissing at every man who came to them smelling of ink.

I wish I had the fire in your belly, the poet says, and Jeoffry knows he is speaking of the creditors again. You would give them a fight, eh? But I fear I have not your courage. I will promise them their paper and perhaps scratch out a stupidity or two, but I cannot do it, Jeoffry. It takes me away from the Poem. What is a man to do, when God wants him to write one poem, and his creditors another?

Jeoffry considers his poet’s problem as he licks his fur back into place. He’d heard of the Poem before—the one true poem that God had written to unfold the universe. The poet believes it is his duty to translate this poem by communing with God. His fellow humans, on the other hand, think the poet should write silly things called satires, as he used to do. This is the kind of thing humans think about, and fight about, and for which they chain up their fellow humans in nasty sweaty madhouse cells.

Jeoffry does not particularly care about either side of the debate. But—he thinks as he catches a flea and crunches it between his teeth—if he were to have an opinion, it would be that the humans should let the man finish his Divine Poem. The ways of the Divine Being were unfathomable—he’d created dogs, after all—and if the Creator wanted a poem, the poet should give it to him. And then the poet would have more time to pet Jeoffry.

O cat, the poet says, I am glad of your companionship. You remind me how it is our duty to live in the present moment, and love God through His creation. If you were not here I think the devil would have claimed me long ago.

If the poet were sane, he might have thought better of his words. But madmen do not guard their tongues, and cats have no thoughts of the future. It’s true, something does occur to Jeoffry as the poet speaks—some vague sense of disquiet—but then the man scratches behind his ears, and Jeoffry purrs in luxury.

* * *

That night, Satan comes to the madhouse.

Jeoffry is curled at his usual spot on the sleeping poet’s back when the devil arrives. The devil does not enter as his demons do, in whispers and the patterning of light. His presence steals into the room like smoke, and as with smoke, Jeoffry is aware of the danger before he is even awake, his fur on end, his heart pounding.

“Hello, Jeoffry,” the devil says.

Jeoffry extends his claws. At that moment, he knows something is wrong, for the poet, who normally would wake with a howl at such an accidental clawing, lies still and silent. All around Jeoffry is a quiet such as cats never hear: no mouse or beetle creeping along a madhouse wall, no human snoring, no spider winding out its silk. It as if the Night itself has hushed to listen to the devil’s voice, which sounds pleasant and warm, like a bucket of cream left in the sun.

“I thought you and I should have a chat,” Satan says. “I understand you’ve been giving my demons some trouble.”

The first thought that flashes into Jeoffry’s head is that Satan looks exactly as Milton describes him in Paradise Lost. Only more cat-shaped. (Jeoffry, a poet’s cat, has ignored vast amounts of Milton over the years, but some of it has apparently stuck.)

The second thought is that the devil has come into his territory, and this means fighting!

Puffing himself up to his utmost size, Jeoffry spits at the devil and shows his teeth.

This is my place! he cries. Mine!

“Is anything truly ours?” The devil sighs and examines his claws. He is simultaneously a monstrous serpent, a mighty angel, and a handsome black cat with whiskers the color of starlight. The cat’s whiskers are singed, the serpent’s scales are scarred, and the angel’s brow is heavy with an ancient grievance, and yet he is still beautiful, in his way. “But more of this later. Jeoffry, I have come to converse with you. Will you not take a walk with me?

”

Jeoffry pauses, considering. Do you have treats?

“I have feasts awaiting. Catnip fresh from the soil. Salted ham from the market. Fish heads with the eyes still in them, scrumptiously poppable.”

I want treats.

“And treats you shall have. Come and see.”

Jeoffry trots at the devil’s heels down the madhouse stairs, past the mouse’s nest on the landing, past the kitchen with its pleasant smell of bread and pork fat, through the asylum’s heavy door (which stands mysteriously open), and onto roads of Darkness, beneath which the round orb of Earth hangs like a jewel. Jeoffry gazes with interest up at the blue glow of the Crystalline Firmament, at the fixed stars, and at the golden chain of Heaven, from which all the Universe is suspended. He feels hungry.

“Well,” the devil says presently. “Let’s get the formalities out of the way.” He snaps his fingers. Instantly Jeoffry is dangling above the Earth, staring down at it as one does at a patterned carpet. He can see the gleaming rooftop of the madhouse, and Bethnal Green, and the darkened streets of London, still bustling, even at this time of night.

“All of this could be yours,” Satan says. “Yea, I will give you all the kingdoms of Earth if you’d but bow down and worship me.”

Jeoffry does not like being dangled. His fur bristles as he prepares himself to fall. But then he catches the smell of the fish market in the air, and hears the distant yowl of a tomcat making love on the street. And Jeoffry understands, for a moment, what the devil is offering him. He understands, also, that this offer represents a fundamentally wrong order to the universe.

You should bow down and worship Jeoffry!

“Right,” the devil says. “I thought as much.”

He snaps his fingers again, and they are back on the path between the fixed stars, with the planets far below them.

“You have the sin of pride, cat,” Satan says. “A sin I am particularly fond of, given that it is my own. For that reason I am taking you into my confidence. You see, I have an interest in your poet.”

Mine!

“That’s debatable. There are multiple claims to Mr. Smart. The Tyrant of Heaven’s, his debtors’, his family’s … the man is like a ruined estate, overrun with scavengers. Me,” the devil shrugs, “he owes for some of his earlier debaucheries—he was an extravagant man in his youth—and for that I need to collect.”

Jeoffry’s tail twitches back and forth. Like many who have conversed with the devil, he can sense something wrong with this dark tide of speech, a lie buried beneath Satan’s reasonable arguments. But he cannot work out what it is.

“Now,” says the Adversary, “I would be willing to forgive this debt if your poet would but write me a poem. I have the perfect thing in mind: a metered piece of guile that, unleashed, would lay waste to Creation.

“Indeed,” the devil says, “I have planted this poem in his imagination on several occasions. But your poet is stubborn. He defies all his creditors (including, most importantly, me), and insists on writing this tripe, this vile piece of sycophancy, for the Tyrant of Heaven, who—let me assure you—deserves no such praise.”

The Poem of Poems, Jeoffry says.

“Exactly. Let us face facts, Jeoffry. The Poem your human labors over—the thing to which he has devoted his last years of labor, burning away his health, destroying his human relationships—even setting aside my feelings on its subject matter, Jeoffry, the fact is this: The poem he writes is not very good.”

Jeoffry stares at his paws, and beneath them, at the blue glow of Earth. Vaguely the words of the poet’s human visitors come to him. Have they not said much the same thing?

“Speaking as a critic now, Jeoffry: Do you not think the poem’s Let-For structure is overly complicated? The wordplay in Latin and Greek too obscure to suit the common taste? Obscurity for the sake of obscurity, Jeoffry. It will get him nowhere.”

Poetry is prayer, Jeoffry says stiffly, repeating the words the poet murmurs to himself as he scratches frantically at his papers, or the bricks, or at the skin on his forearms.

“Poetry is poetry. Two roads diverging in a yellow wood, people wandering about like clouds, even that terrible thing about footprints—that’s what readers want, Jeoffry. Something simple, and clear, with a message: that all of one’s life choices may be justified by looking at daffodils; that we exist in a world abandoned by God and haunted by human mediocrity. Don’t you agree?”

Jeoffry does not like literature of any kind, unless it is about Jeoffry. Even then, petting is better. And eating. Are there treats now?

“Ah, treats.”

Instantly a banquet table is before Jeoffry. Everything the devil had promised is there: the fish heads, the salted ham—and things he forgot to mention, like the vats of cream and crispy salmon skins. There’s even a bowl of Turkish delight.

Jeoffry bolts toward the food. Suddenly, a hand catches him by the scruff of the neck. The devil has grown gigantic, a mighty warrior, singed and scarred by his contest with heaven. His smile gleams like a knife.

“Before you eat, Jeoffry, I need a thing of you. Such a small thing.”

I want the food.

“And you shall get it, if you but promise me this: to stand aside when I come to visit your poet tomorrow night. Aye, to stand aside, and not interfere.”

The uneasy sense that Jeoffry had felt at the devil’s first words returns with a vengeance.

Why?

“Merely so I can converse with your poet.”

Jeoffry thinks about Satan’s proposition. As a cat well-versed in Milton, he is aware of the devil’s less-than-salubrious reputation. On the other hand, there’s a giant vat of cream right there.

I agree, he says.

The devil smiles. Released, Jeoffry flies to the table, and food! There is so much food! He eats and eats, and somehow there is still more to eat, and somehow he can keep eating, though his belly is starting to hurt.

“My thanks to you, Jeoffry,” the devil says. “I will see you tomorrow.”

Jeoffry is aware, vaguely, that Satan is walking away from him. But that does not matter: He has come to the bowl of Turkish delight, and having heard so much about it, it must taste good, no? So he selects a powdered cube of honey and rosewater, one that is larger than all the others, and he takes a bite—

* * *

The next day, Jeoffry feels ill.

On waking, he performs his morning prayers as he always does. He wreathes his body seven times around with elegant quickness. He leaps up to catch the musk, and rolls on the planks to work it in. He performs the cat’s self-examination in ten degrees, first, looking on his forepaws to see if they are clean, then stretching, then sharpening his claws by wood, then washing himself, then rolling about, then checking himself for fleas.…

Yet none of this makes Jeoffry feel better. It is as though something casts a shadow upon him, separating the cat from the sunlight that is his due. With a chill, Jeoffry remembers his bargain with the devil. Was it a dream?

Well met, Jeoffry, well met. The poet is awake, and his eyes look unusually clear. He sits up on his bed of straw, and stretches.

I feel better today, Jeoffry, as if my sickness is leaving me. Oh, but they are sure to duck me again, to drive the devils out. You are lucky, cat, to have no devils in you, for you’d hate being ducked.

The poet rubs Jeoffry’s head, affectionately, then looks again. But how’s this, Jeoffry? You look unwell, my friend.

Jeoffry meows. His stomach feels sickly heavy, as though he has eaten a barrel full of rotten fish. He tries to say something about the devil—not that the human would understand, but it seems worth trying—and instead vomits on the poet’s leg.

Heavens, Jeoffry! What have you been eating!

Jeoffry noses his vomit to see if there’s anything there worth re-eating, but the remnants of the devil’s meal are a pile of dead leaves, partly digested. The devil’s visit was no dream, then.

The poet tries to catch him, but

Jeoffry is too quick. He slips down the staircase, where he vomits, to the kitchen, where he vomits, until he sees a water bowl put down for the physician’s dog. He drinks from it. And vomits.

He vomits on the cook, who tries to catch him, and on the terrier-dog, which yaps at him as he jumps to the top cupboard. Is there so much vomit in the world? (Apparently.)

Miserable Jeoffry curls up on top of the cupboard and puts a paw over his eyes to shut out the light. He sleeps an uneasy sleep, in which Satan stalks through his dreams in the guise of a giant black cat, chuckling.

When Jeoffry opens his eyes again it is evening. He can hear the grind and clink of iron keys above him. The keepers are locking the cell doors. Soon the demons will arrive in full force, to gambol and chitter in the shadows, and pull at the lunatics’ beards, and drive them madder.

Jeoffry clambers to his feet. His legs are shaky, but he drives himself onward, leaping awkwardly to the kitchen floor. The smell of his vomit still hangs in the air, acrid, with an aura of sulfur.

Jeoffry climbs the stairs. The mice behind the walls peep at him as he lumbers past. The imps giggle in the distance, but he sees none in the hallways of the second floor. With a sinking heart, he paces onward, to the room where his poet sits, composing his great work.

As Jeoffry approaches the poet’s cell, a great wind seems to blow from its door. Jeoffry flattens himself against the ground and tries to slink forward, but the wind is too strong. It presses on him with the hands of a thousand dark angels, with the weight of Leviathan, with the despair of the world. He claws at the floorboards, shredding wood, but he cannot go farther.

“Now, now, Jeoffry,” a voice says in his head. “Did you not promise me that you would stand aside?”

Jeoffry yowls in response. He tries to tell the devil that he takes back his bargain, that the food he ate was merely vegetation, that he vomited it all up anyway, that Turkish delight is overrated.

Scardown

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

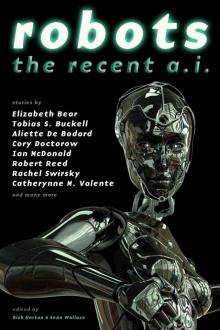

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3