- Home

- Elizabeth Bear

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Page 5

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Read online

Page 5

“A bargain is a bargain,” the voice says. The wind grows stronger. Jeoffry feels himself floating up in the air. A sudden gust jerks him backward, and then—

* * *

Jeoffry wakes. There is a sour smell in the air—not vomit this time, but something else. Jeoffry is lying in the second floor’s empty cell, the one where the human strangled herself on her chains. The iron hoops stare at him accusingly.

Jeoffry uncoils himself, and as he does so he remembers the previous evening. The devil, the wind, and the vomit. (O the vomit!) And the poet.

He takes off at a run. The poet is sitting up on his bed of straw, his face slack-jawed. Jeoffry headbutts him, and winds around him, and paws his face. Even so, it takes a while for the poet to transfer his gaze to Jeoffry.

O cat, the poet says. I fear I have done a terrible thing.

Jeoffry rubs his chin against the man’s skinny knee. He purrs, willing the world repaired.

Last night the devil himself came to me, the man says. He said such things … I withstood him as long as I could, but in the end, I could take no more. I begged him, on my knees, to stop his whisperings. And he asked me—and I agreed. O cat, I am damned for certain! For I have promised the devil a poem.

As he gave this speech, the man’s hands kneaded Jeoffry’s back harder and harder, digging into his flesh until it hurt. Normally this would trigger a clawing, or a stern meow, but Jeoffry understands now what it means to come face-to-face with the devil, and his heart is sore.

Jeoffry does what he can to comfort the poet. He spraggles and waggles. He frolics about the room. He takes up the wine cork the man likes to toss for him, and drops it on the poet’s lap. And yet none of this seems to lift the poet’s spirits.

The man curls in the corner and moans until the attendants come to take him away for his morning ducking. Jeoffry lies on the floor, in the sun, and thinks.

The poet is miserable, and well he might be, having agreed to write a poem for the devil. Jeoffry, in agreeing to stand aside, left his human undefended. In that action (and here Jeoffry must think very hard, and lay his ears back) Jeoffry has been less than his normal, wonderful self. He may in fact have been (though this is almost impossible to think) a bad cat.

Jeoffry is furious at the thought. He attacks the air. Growling, he flies about the room, ripping the spiderwebs down from the ceiling. He gets in the man’s straw bed and whirls around and around, until bits of straw coat the floor and the dust veils him in yellow. Somehow, none of it helps.

When he is exhausted, he sits and licks himself clean. Even a short poem will take the poet more than a day to write, for he must doubt every word, and scratch it out, and write it down again. That is more than enough time for Jeoffry to find the devil, and fight him, and bite him on the throat.

It is true that the devil is bigger than the biggest rat Jeoffry has ever fought, and it is also true that he is Satan, the Adversary, Prince of Hell, Lord of Evil. Nevertheless, the devil made a grave mistake when he annoyed Jeoffry. He will pay for his insolence.

Thus resolved, Jeoffry goes in quest of food. His heart feels lighter. He has a feeling that soon, all will be well.

* * *

When he comes back from his ducking, the poet lies on his bed and weeps. Jeoffry cannot rub against him after the water treatment, for the poet’s skin is still unpleasantly damp. So Jeoffry claws the wooden bedframe instead.

Ah, Jeoffry, the poet cries. They gave me back my paper! And my quill, and ink! Yesterday I would have been overjoyed at such a kindness, but now I can only detect the machinations of the devil! It is all in my head, Jeoffry—the poem entire. I need only set it to paper. But I know I must not. These words—oh they must not be allowed to enter this world!

And yet he takes out a sheet of cotton paper, and his gum sandarac powder, and his ruler. Sobbing, he begins to write. The noise of his quill scritch-scritching is like the sound of ants eating through wood. It wrinkles Jeoffry’s nose, but he does not stir from the poet’s cell. He is waiting for the devil to arrive.

Sure enough, come nightfall, the devil steals into the madhouse. He looks for all the world like a London critic, in a green striped waistcoat and a velvet coat. He stands outside the bars of the cell and peers inside.

“How now, Jeoffry,” Satan says. “How does my poet fare?” It is plain to see that the poet is shivering and sobbing on his bed. At the sound of the devil’s voice, he buries his face in his hands and begins murmuring a prayer.

Jeoffry turns disdainfully to the wall. The devil tricked him. The devil is bad. The devil may not have the pleasure of stroking Jeoffry or petting him on the head. Jeoffry is more interested in staring at this wall. Staring intently. Maybe there is a fly here, maybe not. This wall is more interesting than you, Satan.

“Alas,” Satan says. “Much as it wounds me to lose your good opinion, Jeoffry, tonight I have other fish to fry.” With that, Satan directs his attention to the poet, and he says in the language of the humans: “How goes my poem?”

Get behind me, Satan!

“Please,” the devil says, hooking his hands in the lapels of his coat. “’Tis a sad thing when a wordsmith resorts to clichés. And hardly good manners in addressing an old friend! What, did I not aid you in your youth many a time, in bedding a wench or evading a creditor? Now I ask that you do a single thing for me, and you whimper about repaying my kindness? For shame.”

I should not have agreed to it! the man says. Forgive me, Lord, for I was weak!

“La,” the devil says, “aren’t we all. But enough of this moping. How goes my poem?”

The man is jerked upright like a dog yanked on a chain. He rises from his bed—in his nightclothes, no less—and takes up a few sheets of paper. He hands them, with an iron-stiff arm, through the bars to the devil.

The devil takes out a pair of amber spectacles and a red quill. He reads over the papers with great interest, from time to time making happy humming noises to himself, and from time to time frowning and scratching down something in bursts of flame. “Capital phrasing sir!” he says, and “Sir, you cannot rhyme love with dove, it is banal and I shall not allow it,” and “I like this first reference to ‘An Essay on Man,’ but this second makes you seem derivative, don’t you think?”

The poet, peering at the pages from the vantage point of his madmen’s cell, looks miserable. Jeoffry, inside the cell, begins to growl. Will not the devil come inside? Very well, then Jeoffry will come to him.

“This is marvelous work, sir,” the devil says, slotting the manuscript back between the poet’s trembling fingers. “I am very pleased with your progress. Do contemplate the edits I suggested. I will be back tomorrow midnight to collect the final version.”

I will not do it!

“But you shall, good sir. You have made your bargain. Now, you can sit here, wallowing in misery, or you can comfort yourself that your poem will inscribe itself on the hearts of men. It is all the same to me.”

During this conversation, Jeoffry slips through the bars. The devil is wearing an elegant pair of French boots—of course the devil would favor French leather, thinks the very English Jeoffry—and when the devil turns on his heel, Jeoffry pounces.

Claw and bite! Snap and climb! Jeoffry is simultaneously attacking a black cat with wicked claws and a mighty dragon of shining scale and a gentleman who is trying to shake him off his leg. Jeoffry is tossed by the devil like the Ark on the waves of destruction. He is smashed and crashed, bitten and walloped. Still, Jeoffry clings to him, growling and clawing!

“Oh bother,” says the devil. “Those were my favorite stockings.”

Fire and darkness! Shade and sorrow! The devil has shaken him off. Jeoffry flies through the air and skids across the floorboards. But instantly he is on his feet again, his eyes ablaze, his skin electric. He will not let the devil go!

“Must we?” says the devil wearily. “Oh very well.”

Now the devil begins to fight in earnest, and he is a terror

. He is a thousand yellow-toothed rats swarming out of a sewer. He is a mighty angel whose wingbeats breed hurricanes. He is a gentleman with a walking stick. Wallop!

Jeoffry’s chest explodes with pain. Dazed, for a moment he thinks he cannot rise. But he must, and his legs carry him back into the fight.

Jeoffry stalks the devil anew, trying to keep clear of Satan’s walking-stick wings. Suddenly the black cat is there, clawing at Jeoffry’s eyes and springing away before Jeoffry can land a blow. Jeoffry hisses and puffs up his fur, but somewhere in his aching chest is the sense that, perhaps, this is a fight he cannot win. Perhaps this is the fight that kills Jeoffry.

So be it. Jeoffry leaps on the back of the cat/rat/angel/dragon. He draws blood, the devil’s blood, which smells of burning roses.

Too quickly, the devil twists under his grip. Too quickly, the yellow teeth clamp down. Agony sears through Jeoffry’s neck. The devil has him by the throat.

Jeoffry struggles for purchase, but he can find none. His vision darkens. He can feel the devil’s teeth press hard against the pulse of his life.

Dimly he hears the poet yelling. No, no! the man cries. Please spare my cat! We’ll cause you no more trouble, I swear!

The devil loosens his grip. “Ooph ooph,” he says. He spits out Jeoffry and tries again. “Very well.”

And Jeoffry is falling through blackness, falling forever—

* * *

Jeoffry is in pain. The bite the devil gave him throbs fiercely. It is in the wrong place to lick, and yet he tries, and that hurts too.

Poor Jeoffry! Poor Jeoffry! the poet says. O you brave cat. May the Lord Jesus bless you and your wounds.

Jeoffry’s ears flick back and forth. Worse than the pain is the heaviness in his chest that comes from having lost a fight. Jeoffry lose a fight! Such things were possible when he was a kitten, but now—

I can feel the paper calling to me even now, the poet sighs. O Jeoffry, sleep here and grow well again. I must to my task.

At this Jeoffry leaves off licking his wounds and stares at the poet. He means to convey that the man should not write this poem. For once, the man seems to understand.

O Jeoffry, I have made a deal, and I feel in my bones that I cannot fight it. When I hand him that poem, I will give him my very soul! But what can be done? There is nothing to be done, Jeoffry. You must get better. And the poem must be written.

Jeoffry does not even have the strength to protest. He drinks from the water bowl the poet has put near him, and sleeps for a while in the sun.

When he opens his eyes the afternoon light is slanting through the barred window. Clumsily, Jeoffry rises and performs his orisons. As he cleans himself he considers the problem of the devil and the poet. This is not a fight Jeoffry can win. The traitorous thought clenches his throat, and for a moment he wants to push it away. But that will not help the poet.

So instead, Jeoffry does what he never does, and considers the weaknesses and frailties of Jeoffry.

Magnificent though he is, he thinks, Jeoffry is not in himself enough to defeat the devil. Something else must be done. Something humbling, and painful.

Once he is resolved, Jeoffry slips out of the cell. He does not take up his customary spot under the kitchen table, but instead limps into the courtyard, to where the cook has laid out a bowl of milk for the other cats, the ones who do not rule the madhouse.

Polly is the first to appear. She is an old lover of his, a sleek gray cat with a tattered ear and careful deportment. She looks distressed to see his wounds.

Jeoffry says.

Polly investigates Jeoffry’s wounds.

Polly leans forward and licks the bite. Jeoffry flicks his ears back, but accepts her aid. It is the first good thing that has happened this day.

Next comes Black Tom, the insufferable alley cat.

Jeoffry and Black Tom both mutter apologies.

The Nighthunter Moppet yawns open her small pink mouth, then closes it. She looks around her, puzzled.

says Polly.

The kitten falls on the milk and drinks her fill. When she is done she skips around the bowl, batting at the adults’ noses. When she reaches Jeoffry, though, she stops, and looks concerned.

Jeoffry says.

O! The kitten’s green eyes widen. She sits back into the bowl of milk, sloshing it over her bottom.

The kitten, who had been licking up the spilled milk, turns her attention back to Jeoffry.

Jeoffry sighs.

And he tells them everything: the magnificent cat-bribing feast, the vomit, the fight with Satan, the poet’s despair. The other cats watch him wide-eyed.

At the end of his tale, he hunches into himself and speaks the words that are hardest in the world for a cat to utter.

The other cats look at him in amazement. Jeoffry feels shame settle on him like a fine dust. He drops his gaze and examines the shine of a brown beetle that is slowly clambering over a cobblestone.

All kittenness has fallen away from Moppet. What sits before the milk bowl is the ruthless killer of the courtyard, the assassin whose title nighthunter is whispered in terror amon

g the mice and birds of Bethnal Green. It is rumored that the Moppet’s great-grandmother was a demon of the lower realms, which might perhaps explain the peculiar keenness of her green-glass eyes, and her talent for death-dealing. Indeed, as Jeoffry watches, the Moppet’s tiny shadow seems to grow and split into seven pieces, each of which is shaped like a monstrous cat with seven tails. The shadow cats’ tails lash and lash as the Nighthunter Moppet broods on Satan.

The Nighthunter Moppet sighs at the thought of a lost kill, and drops her gaze to the ground. The brown beetle is still there, trotting over the cobblestones. She begins to follow it with her nose.

The kitten’s shadows turn and look at Black Tom with disapproval. When she next speaks, their voices join hers. They sound like the buzzing of a thousand flies.

says Black Tom.

Scardown

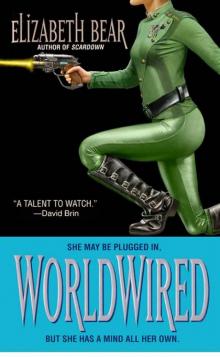

Scardown Worldwired

Worldwired Ancestral Night

Ancestral Night Hammered

Hammered The Red Mother

The Red Mother The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two

The Red-Stained Wings--The Lotus Kingdoms, Book Two Machine

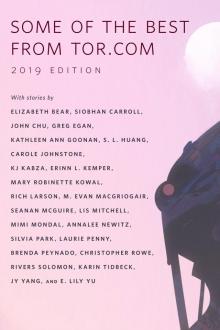

Machine Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2019 Edition Faster Gun

Faster Gun In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns

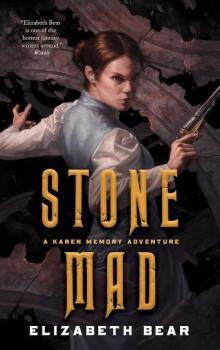

In the House of Aryaman, a Lonely Signal Burns Stone Mad

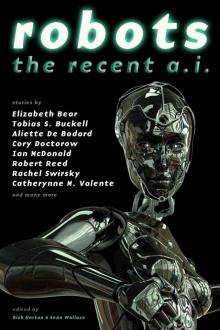

Stone Mad Robots: The Recent A.I.

Robots: The Recent A.I. The Tempering of Men

The Tempering of Men Boojum

Boojum Book of Iron bajc-2

Book of Iron bajc-2 The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010

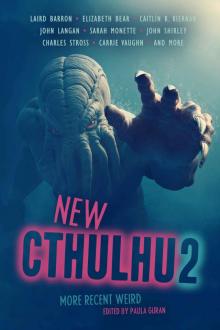

The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2010 New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird

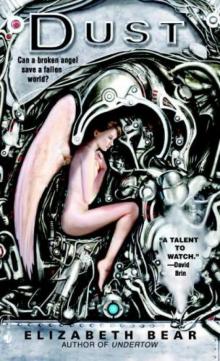

New Cthulhu 2: More Recent Weird Dust jl-1

Dust jl-1 Worldwired jc-3

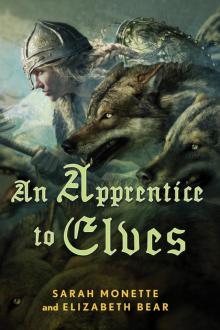

Worldwired jc-3 An Apprentice to Elves

An Apprentice to Elves Hammered jc-1

Hammered jc-1 Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle

Crowd Futures: We Have Always Died in the Castle Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1

Bone and Jewel Creatures bajc-1 Carnival

Carnival Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best from Tor.com: 2012 Edition: A Tor.Com Original The Stone in the Skull

The Stone in the Skull Scardown jc-2

Scardown jc-2 Hell and Earth pa-4

Hell and Earth pa-4 Undertow

Undertow Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep

Mermaids and Other Mysteries of the Deep A Companion to Wolves

A Companion to Wolves Ink and Steel pa-3

Ink and Steel pa-3